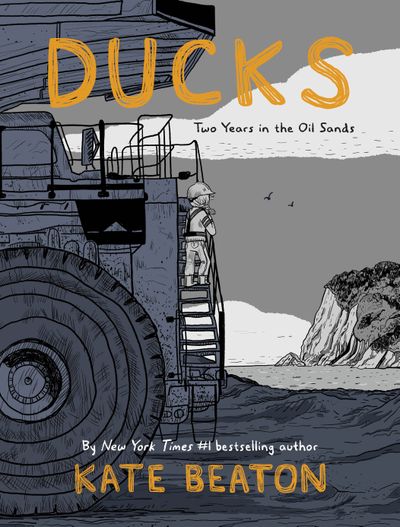

Book review: In Kate Beaton’s ‘Ducks,’ personal trial collides with economic flux

For the women who migrated to work in the bitumen-rich tar sands of northern Alberta in the early 21st century, there were many ways for the gritty environment to turn toxic. Kate Beaton depicts the experience of being far outnumbered by men in her powerful new graphic memoir, “Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands,” which finds her younger self, Katie, dealing with the leering attentions of some male co-workers.

Beaton, a gifted Canadian cartoonist, first burst onto the scene about 15 years ago with her popular history-and-literature-laced webcomic, “Hark! A Vagrant.” Since then, she has published collections of her “Hark!” humor, which deftly blends jabs at famous men of patriarchal privilege (see, for instance, her Andrew Jackson takedowns) with plaudits for heroic but undersung women (among them Ida B. Wells). She also has created such picture books as “The Princess and the Pony,” which has spawned an Apple TV+ animated series.

Beaton’s soulful masterwork, “Ducks,” her first graphic memoir, documents a period of her life – from 2005 to 2008 – before her comics brought her to public attention. Eschewing the distancing irony that characterized many of her “Vagrant” comics, it is the most gripping graphic memoir of 2022, offering an unblinking tale of personal trial set against a nation in economic flux.

Beaton is from Cape Breton Island, on Canada’s eastern shore, where coal was once king; the industry’s sinking fortunes are also stripping the financial hopes of Nova Scotians (“We’re fiddles and lobster,” she says of her home province) and nearby Newfoundlanders (“accordions and codfish”). Lives are calibrated to regional boom-and-bust trends.

“I learn, by twenty-one, that any job is a good job,” Beaton writes. “Even a bad job is a good job; you’re lucky to have it.” As oil prices soar and employment opportunities open up in Alberta, she sees a way to “sever that weighted anchor” of about $40,000 in student debt.

Yet just where has she landed?

When she reports to a tool crib for the company Syncrude, Katie must deal with the dehumanizing reality of laboring in an environment where the male-to-female ratio is about 50-to-1. And as the resilient Katie moves from one work site to another in the oil sands – adapting to the social dynamics of different locations – Beaton expertly depicts the complexities of operating in misogynistic spaces, where sexual harassment is common. “All you need here is to be a woman,” Katie realizes. “You stick out, and that’s all it takes … and someone thinks they like you. But that doesn’t make me feel good. That makes me feel like I’m not even a person.”

Beaton also underscores the effects of the energy industry upon animals, sometimes treating them as metaphors for the human toll of the businesses that employed her. Reflecting on the eastern shore, Katie sings a song about the coal industry, in which ponies are forced to “pull till they nearly break their backs.” And in Alberta, she reports, the oil industry makes headlines when hundreds of ducks die after landing in Syncrude’s “toxic sludge” of a tailing pond. These waterfowl, she implies, have become as mired in the muck as the employees are in the tar-sand culture.

In this oily setting that imperils so many birds, the reader worries for Katie all the more when a co-worker casually refers to her as “ducky.”

Beyond her own difficulties, Beaton provides a wider lens on a brutal makeshift culture that leaves some workers stressed, depressed and lonely. In the afterword to “Ducks” – which she began creating in 2016 – Beaton considers camp life with profound empathy, weighing how the individual can get ground down by the methods and machinery of Big Energy. In Beaton’s experience, the Alberta work camps were a “capsuled-off society” that fostered challenges of all kinds. Some workers turned to alcohol and cocaine to cope; others were fired if they sought employee assistance, she shows – while real discussion about mental health “barely existed.”

“The industry prized itself on having millions of hours without lost time incidents,” she writes, “while hiding the human wreckage.”

Mining ever deeper into her own experiences, Beaton poignantly captures how she and her colleagues shouldered the burdens of work in the oil sands. It is not until Katie flees Syncrude that she realizes how much – and for how long – she had swallowed self-dignity in the service of survival. Beaton also leads us through her other realizations over time, including how Alberta’s oil business operates on stolen lands – just one aspect of how Indigenous people in the area have been exploited.

Throughout “Ducks,” Beaton’s pen conveys a sense of moody displacement. Camp life can feel as bleak as the book’s monochromatic grays, and we encounter so many stoic faces that we begin to question what lurks behind the sudden smile of a co-worker. She also occasionally pulls back, drawing sweeping panoramas of the landscape that remind us of the natural beauty (ah, the northern lights) amid the towering cranes and smokestacks – an aesthetic tug of war over what will survive.

Beaton respects that many people – many families – have mostly positive associations with Canada’s oil industry. “Ducks” provides a complex picture from a specific era, not a simple critique.

“Everyone’s oil sands are different,” she writes, “and these were mine.”