Mothers gather in Olympia to receive first birth certificates for stillborn babies

OLYMPIA – Twenty-one years ago, Candy Wright received a death certificate for her daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, but she never received a birth certificate.

Wright, from Vancouver, Washington, had been pregnant with Sarah Elizabeth for a full term, but when she went into labor, there was no heartbeat. The umbilical cord had wrapped around her daughter twice, and the result was a stillbirth.

On Monday – 21 years to the day that the death certificate was signed – Wright finally received what she and so many other Washington mothers like her have long awaited: a birth certificate for their child who was stillborn.

“I was always just so afraid she would be forgotten,” Wright said.

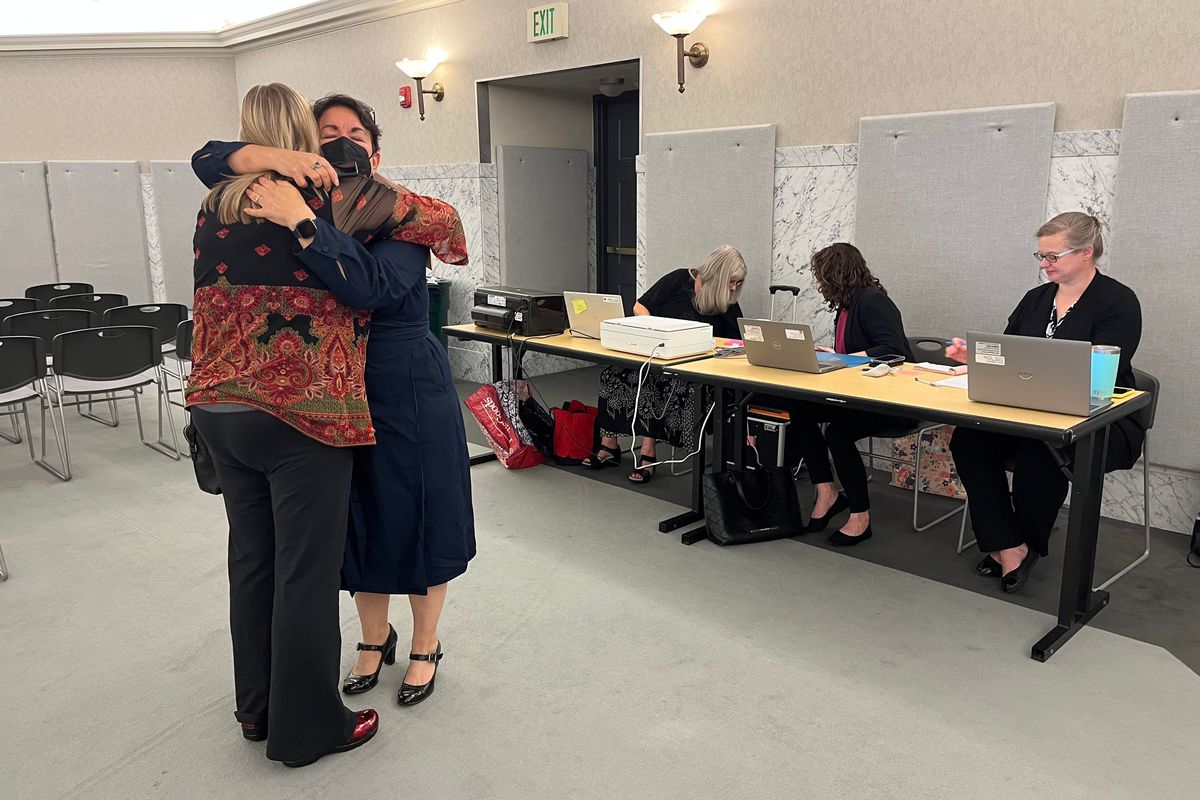

Wright joined five other women at the state Capitol on Monday to receive the state’s first birth certificates for deliveries resulting in stillbirth.

After passing a law last legislative session, Washington became the 44th state in the country to allow families to request birth certificates. The law went into effect Saturday.

Families who want to order a birth certificate can do so through the Department of Health. The law is retroactive, and the department currently has records from Jan. 1, 1957, to the present.

Under the law, the person who delivered a stillborn fetus may apply for a certification of birth resulting in still birth, a fetal death certificate, or both, with the state or local registrar. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated there were about 24,000 stillbirths in 2014.

Before the law was in place, families were only given death certificates once their child was born.

Some women have been writing letters to legislators and pushing for birth certificates for their stillborn children for last the 20 years.

After having a stillbirth in 2007, Abrams-Caras, a former lobbyist, started the push in Washington to allow birth certificates for stillborn children.

“I thought it would be an easy thing,” she said.

Instead, it took years of bills failing to make it out of committee or not receiving enough votes in one of the chambers.

The bill had a number of hurdles during the last 20 years, including being a topic that is often caught up in a debate about abortion access.

Carolyn Logue, who lobbied for the legislation in recent years, said she and the mothers worked with the Department of Health, legislators and lawyers at pro-choice and pro-life groups to craft the language in the bill.

The law has a specific definition for stillbirth, which is “any product of conception that shows no evidence of life, such as breathing, beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles after complete expulsion or extraction from the individual who gave birth; is not an induced termination of pregnancy; and has completed 20 or more weeks of gestation or, if weeks of gestation are not known, weighs 350 grams or more.”

Under the law, the certification of birth resulting in stillbirth is in a form similar to a certification of birth but must contain a line at the top that reads: “This certificate of birth resulting in stillbirth is not proof of a live birth and is not an identity document.”

In the first few years, Sarah Bain, from Spokane, said it was difficult when a number of legislators said they couldn’t support the bill. Bain’s daughter, Grace, was stillborn in 2003.

At the time, Bain said all she wanted was some recognition that her child existed. Instead, all she had was a death certificate.

“Grace died on May 29, but was born on June 1,” she said. “It didn’t make any sense.”

After almost 20 years, the legislation passed the Senate unanimously and the House 85-13 in April. All 13 no votes were from Republican legislators.

Receiving Sarah Elizabeth’s birth certificate on Monday was “a lot,” Wright said. It had always been something that nagged at her. Wright has two other children, but said she was so afraid Sarah Elizabeth would be forgotten.

It’s an “emotional tug-of-war,” she said.

“How can you look at life and think you wouldn’t change a thing but wish everything was different?” Wright said.

Bain said she hopes the new law will help other families going through a stillbirth. They should feel validated from the beginning that their baby was born, she said.

Mothers have to request the application for stillbirth, but now they have a right to one, Bain said.

Receiving Grace’s birth certificate on Monday, 19 years later, was a “surreal” moment, she said.

“My daughter was born. She existed,” Bain said. “She matters.”