Supreme Court kicks off new term with North Idaho couple’s case that could limit reach of Clean Water Act

An aerial photograph shows the shore of Priest Lake in Idaho with the property of Chantell and Mike Sackett at top center. The lot has been the subject of a 15-year legal dispute over the Sacketts’ ability to develop the land, which the Environmental Protection Agency considers protected wetland, without going through a federal permitting process. (Courtesy of the Pacific Legal Foundation)

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Supreme Court on Monday kicked off what promises to be another contentious and high-stakes term with oral arguments in a North Idaho couple’s case that could see the court’s conservative supermajority roll back federal protections for the nation’s wetlands.

At issue is what exactly counts as “waters of the United States,” which are protected from pollution by the Clean Water Act of 1972. In previous cases, the high court has agreed the law applies to wetlands – which play important roles, including flood control and filtering pollutants – in addition to “navigable” bodies of water. But in a muddled 2006 decision, the court’s nine justices split three ways, leaving conflicting “tests” for lower courts to apply in deciding if a wetland is protected.

Now, the court will try to resolve that ambiguity through a long-running case that centers on less than an acre of land in North Idaho.

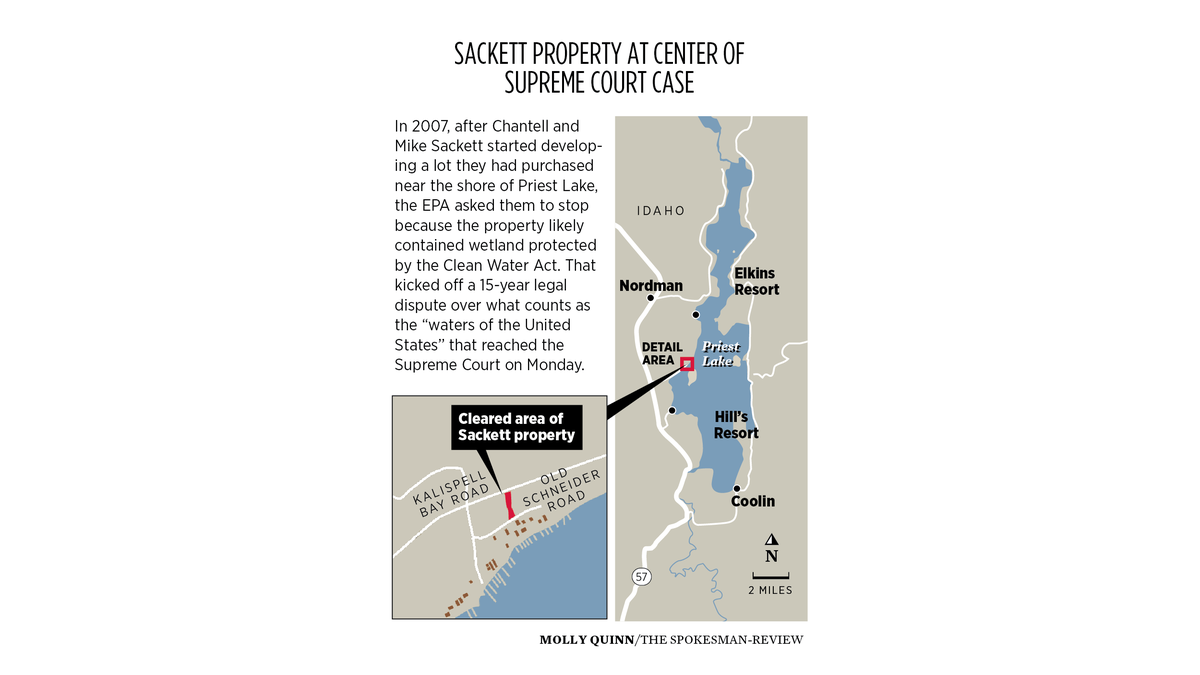

The 15-year legal saga began after Chantell and Mike Sackett bought an undeveloped lot about 300 feet from the shore of Priest Lake in 2004. When they started filling it with sand and gravel to prepare for construction in 2007, the Environmental Protection Agency said that because the property sat on federally protected wetland, the couple needed to obtain a costly federal permit or face heavy fines.

Instead, the Sacketts sued the EPA in 2008 and their case has since wended its way up and down the federal court system, first reaching the Supreme Court in 2012, when the justices ruled unanimously that the couple could immediately challenge the EPA’s order in federal court. When a district court judge in Idaho ruled in favor of the EPA and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld that decision, the Sacketts petitioned the Supreme Court to take another look at their case.

The Supreme Court agrees to hear only about 1% of the cases brought before it. Jerry Long, a law professor at the University of Idaho, said the justices likely chose to consider the Sacketts’ argument for one of two reasons: They wanted either to constrain the federal government’s regulatory authority or simply to clarify a confusing ruling in the 2006 case, Rapanos v. United States.

In that case, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by three of his fellow conservatives, wrote that wetlands should be protected by the Clean Water Act so long as they had “a continuous surface connection” with a navigable body of water, such as Priest Lake. Under Scalia’s definition, the Sacketts argued in their brief, their plot of land should not be federally protected.

In an amicus brief, associations representing water regulators and managers said applying Scalia’s test would exclude at least 51% of the nation’s wetlands from the protection of the Clean Water Act.

But since Scalia’s opinion failed to gain the support of a majority of the court, lower courts have often followed a separate definition offered by former Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote that the statute encompassed any wetland that shared a “significant nexus” with navigable body of water, such that polluting it would affect the “physical, chemical, or biological health” of the clearly protected water.

The Obama administration tried to clear up the ambiguity by making a federal rule based on Kennedy’s test, promptly drawing legal challenges. The Trump administration subsequently created a rule based on Scalia’s test, which is still being challenged in court.

“It’s the biggest mess of overlapping litigation you’ve ever seen,” said Todd Wildermuth, policy director at the University of Washington’s regulatory environmental law and policy clinic.

The Biden administration is in the process of crafting a new rule that aims to combine Scalia’s and Kennedy’s tests, but the Supreme Court’s decision could upend that process, too.

Wildermuth emphasized that Congress could resolve the dispute at any time by passing new, clearer legislation, but that appears unlikely.

The Sacketts asked the Supreme Court to apply Scalia’s test, but in Monday’s oral argument, justices on both sides of the court’s ideological divide expressed concern that such a narrow reading may conflict with the intent of the 1972 law.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, in her first words from the bench since being confirmed to the high court by the Senate in April, got to the crux of the issue.

“You say the question is which wetlands are covered, which I agree with,” Jackson said to Damien Schiff of the Pacific Legal Foundation, the attorney representing the Sacketts. She then asked Schiff why Congress would draw the line “between abutting wetlands and neighboring wetlands when the objective of the statute is to ensure the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the nation’s water?”

At the same time, the court’s six Republican-appointed justices seemed worried that the government’s definition of protected waters is unreasonably vague and risks unfairly penalizing landowners. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked the Justice Department attorney representing the EPA, Brian Fletcher, to define exactly how close a wetland must be from a navigable body of water to be considered “adjacent.”

When Fletcher declined to specify a distance, Gorsuch asked, “So, if the federal government doesn’t know, how is a person subject to criminal time in federal prison supposed to know?”

Stakeholders weighed in on both sides of the argument in dozens of amicus briefs, including the Idaho Conservation League, which argued the Sacketts’ property must be considered “adjacent” to the lake because groundwater flows from their land into the lake.

The Congressional Western Caucus, a group of House Republicans led by Washington Rep. Dan Newhouse of Sunnyside, argued that the Clean Water Act gave the federal government far narrower authority than the EPA has interpreted and said, “local communities are capable of making land use and water decisions far better than a bureaucrat thousands of miles away.”

A group of 18 Native American tribes, including the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, said they depend on the Clean Water Act to protect both waters on their reservation and those off their reservations to which they have treaty rights.

“Tribes have always known what science fully demonstrates: Waters of the United States, including wetlands, are connected, and the Clean Water Act must comprehensively cover waters to protect and restore the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters, consistent with Congress’s purpose and direction,” the tribes wrote.

The court is likely to issue its decision in the Sackett v. EPA case next summer.