Confidence, anxiety and a scramble for votes before midterms

DELAWARE COUNTY, Pa. – The turbulent midterm campaign rolled through its final weekend Sunday as voters – buffeted by record inflation, worries about their personal safety and fears about the fundamental stability of American democracy – showed clear signs of preparing to reject Democratic control of Washington and embrace divided government.

As candidates sprinted across the country to make their closing arguments, Republicans entered the final stretch of the race confident they would win control of the House and possibly the Senate. Democrats steeled themselves for potential losses even in traditionally blue corners.

On Sunday, President Joe Biden was set to campaign for Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York in a Yonkers precinct where he won 80% of the vote in 2020, signaling the deep challenges facing his party two years after he claimed a mandate to enact a sweeping domestic agenda.

Former President Donald Trump planned to address supporters in Miami, another sign of Republican optimism that the party could flip Florida’s most populous urban county for the first time in two decades.

Their appearances will mark an unusual capstone to an extraordinary campaign – the first post-pandemic, post-Roe, post-Jan. 6 national election in a fiercely divided country shaken by growing political violence and lies about the last major election.

While a majority of voters name the economy as their top concern, nearly three-quarters of Americans believe that democracy is in peril, with most identifying the opposing party as the major threat. Should Republicans sweep the House contests, their control could empower the party’s right wing, giving an even bigger bullhorn to lawmakers who traffic in conspiracy theories and falsehoods such as Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Matt Gaetz of Florida.

A central question for Democrats is whether such a distinctive moment overrides fierce historical headwinds. Since 1934, nearly every president has lost seats in his first midterm election. And typically, voters punish the party in power for poor economic conditions – dynamics that point toward Republican gains.

“These people don’t just need to lose. They need to lose by a lot. They need to get the message,” said Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, speaking at a Republican rally in Miami before Trump

After days of campaigning across rural Nevada, Adam Laxalt, the Republican challenging Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, rallied supporters in and around Las Vegas this weekend, predicting a “red wave” that is “deep and wide.” Laxalt noted that Biden did not campaign in Nevada this year and blamed him for the state’s 15% inflation.

“He’s going to call you anti-democratic for using the democratic system to give us a change,” he told supporters Saturday in Clark County, the state’s largest county. “But that change is coming.”

The midterm’s final landscape two days before Tuesday’s election hinted that voters were prioritizing fiscal worries over more existential fears about democracy or preserving abortion rights. From liberal Northeastern suburbs to Western states, Republican strategists, lawmakers and officials now say they could flip major parts of the country and expand their margins in Southern and Rust Belt states that have been fertile ground for their party for much of the past decade.

There were also some early signs that key parts of the coalition that boosted Democrats to victory in 2018 and 2020 – moderate suburban white women and Latino voters – were swinging toward Republican candidates. The first lady, Jill Biden, traveled to Houston on Sunday, trying to lift party turnout in the Democratic stronghold of Harris County and supporting the embattled county leader, Lina Hidalgo.

“We must speak up for justice and democracy,” Biden told the congregation at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, her first stop on a day that was also scheduled to include visits to another Black church and a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood. “We must vote.”

In the House, where Republicans need to flip five seats to control the chamber, the party vied for districts in Democratic bastions, including in Rhode Island, exurban New York, Oregon and California. Republican strategists touted their surprisingly close standing in governor’s races in longer-shot blue states such as New York, New Mexico and Oregon.

At the same time, the Senate remains a tossup, with candidates locked in near dead-even races in three states – Georgia, Nevada and Pennsylvania – and tight races in at least another four. Republicans need just one additional seat to win control.

“Everyone on the Republican side should be optimistic,” Sen. Rick Scott, R-Fla., head of the Republican Senate campaign arm, said in an interview.

Scott predicted his party would flip the chamber, going beyond the 51 seats needed for control. “If you look at the polls now, we have every reason to think we’ll be over 52.”

For months, Democratic candidates in key races have outpaced Biden’s low approval ratings, aided by flawed Republican opponents who had been boosted to primary victories by Trump. Continuing to outrun the leader of their party has grown more difficult as perceptions of the economy worsened and as Republican groups unleashed a fall ad blitz accusing their opponents of being weak on crime.

“It’s a close race – it’s a jump ball for sure,” Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, the Democrat running for Senate in Pennsylvania against Dr. Mehmet Oz, the television personality, told a group of supporters in suburban Philadelphia.

In North Carolina’s Johnston County, Rep. Ted Budd, the Republican who has been locked in a tight Senate race for months, rallied canvassers with a sense that the national conversation had swung in his party’s direction in the past weeks.

“We’re talking about three things out there, because our policies are on the right side: When it comes to inflation, when it comes to crime, when it comes to education, those are the things that people are actually talking about,” Budd said.

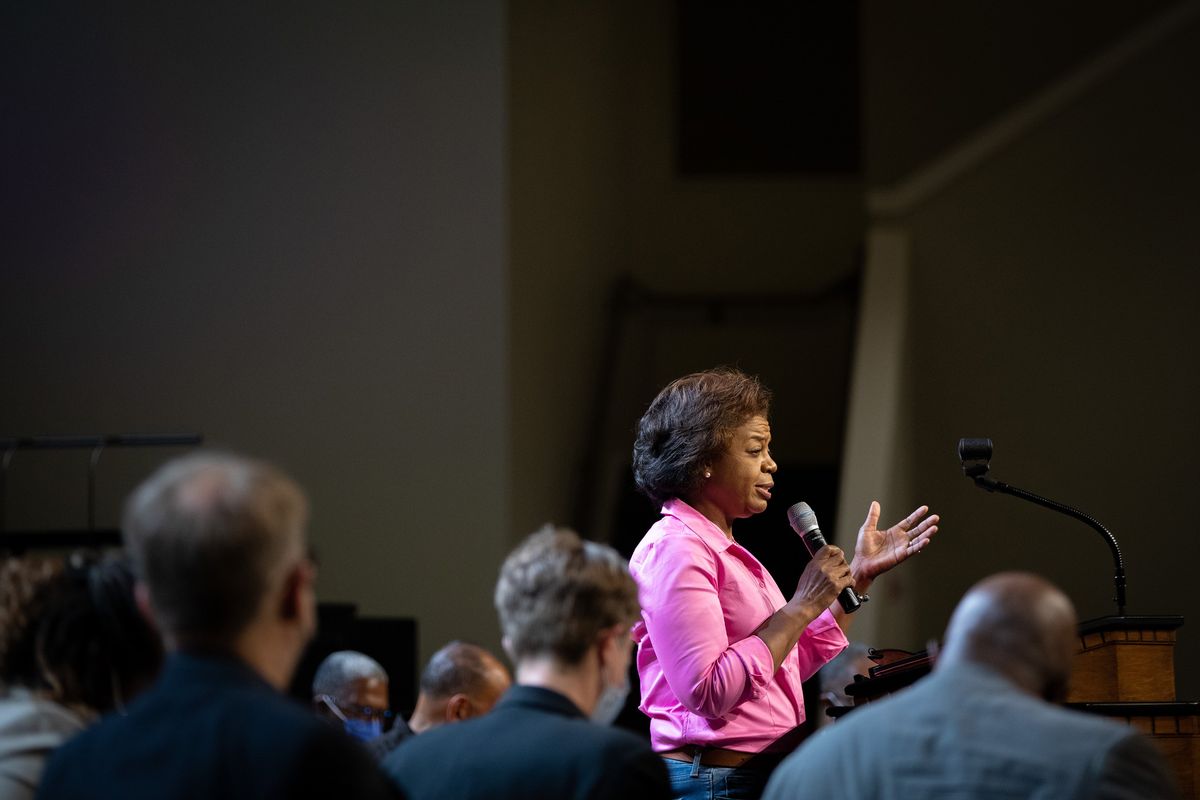

Fifty miles north, in Rocky Mount, Cheri Beasley, his Democratic opponent and a former state Supreme Court chief justice, was pleading with a largely Black audience to get every voter to the polls.

“Somebody fought for us,” she told a cheering crowd under a bright blue sky outside a bandstand at Higher Ground Ministries. “So we have an obligation to fight for the next generation.”

In the House, the question is how large next year’s Republican majority will be. Some strategists have increased their estimates of how many seats the GOP will gain from a handful to more than 25, which is well over the threshold for control of the chamber. Some of the Democratic challenges are structural: Republicans could pick up three seats just from redistricting according to some estimates, and a wave of Democratic retirements means more than a dozen seats in competitive districts lack incumbents to defend them.

Paired with the number of seats leaning Republican or considered tossups, those obstacles are the makings of a landslide if undecided voters break decisively for the party out of power.

“It’s not a surprise that this is a tough cycle,” said Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, the head of the Democratic House campaign arm, who is in danger of losing his seat in New York’s Hudson Valley, which Biden won by 10 percentage points. “We’re very much aware of what we’re up against.”

In governor’s races, Republican candidates modeled after Trump face decidedly mixed prospects, reflecting their party’s struggles with his continued influence. Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida seemed poised for reelection, while Kari Lake, the Republican nominee in Arizona, faces a tough battle. Doug Mastriano, the far-right nominee in Pennsylvania, was expected to lose, but Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia and Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, both of whom clashed with Trump, appear to have solidified their hold.

In some ways, the congressional elections are less consequential than some of the state elections, given that Biden will still be in the White House to block Republican legislation. In Wisconsin and North Carolina, the party is on the verge of breakthroughs in state legislatures that would give it almost total control of their governments.

If Republicans gain just a handful of House and Senate seats in North Carolina, Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, faces the prospect of a Republican supermajority, rendering his veto pen obsolete to stop policies such as a state abortion ban. If Republicans flip only one of the two state Supreme Court seats up for reelection Tuesday, a Republican-controlled high court could ratify even more gerrymandered state legislative maps that would lock in Republican control for the foreseeable future.

“Yes, we’re concerned about it because the Republicans got to draw their own districts,” Cooper said. “We know this is a very purple, 50-50 state, yet we have a situation with unfair maps of maybe a supermajority.”

But the chaotic events of the post-Trump era along with questions about the very mechanics of elections have injected a heavy dose of uncertainty into the outcome of the 2022 midterms.

Democratic strategists have been enthusiastic about early voting, saying that it matched or was higher than the turnout two years ago when the party swept the House. More than 30 million ballots have been cast already, exceeding the 2018 total, and the Democratic advantage is 11 percentage points nationwide, even better than in 2018, according to Tom Bonier, CEO of TargetSmart, a firm that analyzes political data.

But Republican candidates have followed Trump’s lead in denouncing mail voting and encouraging their voters to cast their ballots on Election Day. So those early Democratic numbers could be swamped by Republican votes Tuesday.

Republicans, meanwhile, point to polling averages that crept toward the GOP in the final week. But a number of the polls were conducted by Republican-leaning firms, which could influence the outcome of those surveys. And after several cycles of polling underestimating Trump voters, it’s unclear whether pollsters have correctly captured the electorate.

“I’ve never been one who has put my bets on any poll, because I think particularly at this time people are not sharing where they are,” said Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., who is facing a tough reelection battle in her blue state.

Hispanic voters are likely to play a crucial role in Tuesday’s election, although both sides remain uncertain how much the landscape has shifted. In two of the states that are likely to determine control of the Senate – Nevada and Arizona – they make up roughly 20% of the electorate. Latinos also account for more than 20% of registered voters in more than a dozen hotly contested House races, including in California, Colorado, Florida and New Mexico.

“The data itself right now is a picture of uncertainty,” said Carlos Odio, who runs Equis, a Democratic-leaning research firm that focuses on Latino voters. “We’re not seeing further decline for Democratic support, but the party has relied on very high margins in the past.”