Spokane Parks releases draft master plan with long-term strategies for new amenities, upgrades

Minnehaha Park’s sign is photographed Thursday defaced with graffiti in Spokane. Upgrades to the park are being considered. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

A new community park in the North Indian Trail neighborhood.

At least one dog park and pickleball or multi-use court in each of the city’s three city council districts.

Addressing the role of city parks with homelessness issues.

Those are some of the proposals included in the latest draft of the Spokane Parks and Recreation’s Parks and Natural Lands Master Plan, a document designed to guide investments and development for the city’s approximately 3,800 acres of parks and natural lands over at least the next six years.

Parks and Recreation released the draft last week with the Spokane Park Board set to vote on the document June 9. The ideas within were derived from months of surveys, meetings, workshops and other events

“Now, we’re at a stage where we listened to the public, who gave us great feedback. We drafted a plan,” said Parks Director Garrett Jones. “Now, let us know how we did.”

Park bond initiatives in the past have supported parks improvement projects. Whether the city could take the same route here is a strategy the department will look at in the near future, Jones said.

Parks staff worked with consulting firm Design Workshop to put the draft together. It’s designed as a living document, one that could be updated as funding opportunities, trends and desires change over time.

“There’s a lot of transparency in this plan about what is going to be done, with how and when, that you don’t always get in a plan like this,” said Anna Laybourn of Design Workshop, who headed the consultant team for Spokane’s master plan document. “The city wants to make sure how they’re getting to this overall vision.”

Spokane Parks’ most recent systemwide master plan dates back to 2010. Washington state requires Spokane Parks to have an updated plan for grant funding eligibility through agencies like the Recreation and Conservation Office.

Whereas previous master plans were typically built around input from staff and city officials, Jones said Spokane Parks wanted this iteration to be “a public-facing plan driven by the community.” As such, Parks and Recreation collected more than 5,000 responses through various means, around five times more than what was collected back in 2010.

The level of public input to formulate Spokane’s draft plan exceeded Design Workshop’s expectations as compared to plans the firm has done with similar-sized cities, Laybourn said.

She said the consultant was particularly impressed by the city’s modes of outreach, such as conducting workshops at schools to collect student feedback or recruiting volunteer ambassadors – including those in the homeless community.

“From youth to low-income to every sector of the city being represented, we had a number of ways to measure if we were on track for receiving the type of input we needed to be broad and inclusive,” Laybourn said.

Parks and Recreation – aligned with the thinking of a 1913 plan created by the Olmsted Brothers, a prominent landscape architecture firm – sought to address gaps in areas where parks and other amenities are either unavailable or not easily accessible.

“The biggest theme from this plan is a focus from the community on neighborhood and community parks,” Jones said. “We really haven’t had those major investments in our neighborhood parks since the 1999 bond, and that really only hit a certain percentage of those neighborhood parks.”

Actions proposed to this end include concept plans for revamped versions of Minnehaha and Cowley parks as well as an idealization of what a new park might look like in the North Indian Trail neighborhood.

Currently, Meadowglen Park is a vacant and undeveloped city-owned property located at Indian Trail Road and Bedford Avenue. The city has owned the property since 1986, according to the draft plan.

Compared to the city’s other neighborhoods, North Indian Trail has the highest percentage of residents who live outside of a 10-minute walk to a park, according to the draft plan.

Minnehaha Park is home to overgrown tennis courts, a historic building and a small, aging playground. Meanwhile, Cowley – described as underused, with a reputation marred by past negative activity and vandalism, Jones said – is located next to Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center.

The Minnehaha, Cowley and Meadowglen plans are classified as “first-tier” priorities in the draft document, recommended for implementation sometime over the next decade.

Other first-tier proposals include acquiring property east of South Ray Street in the East Central Neighborhood for the development of a future pocket park as well as land in the Shiloh Hills neighborhood, east of North Nevada Street, for a community or neighborhood park.

Like Meadowglen, the draft also calls for prioritized development of three other vacant park properties in each city district: Wildhorse, Skeet-so-mish and Sterling Heights.

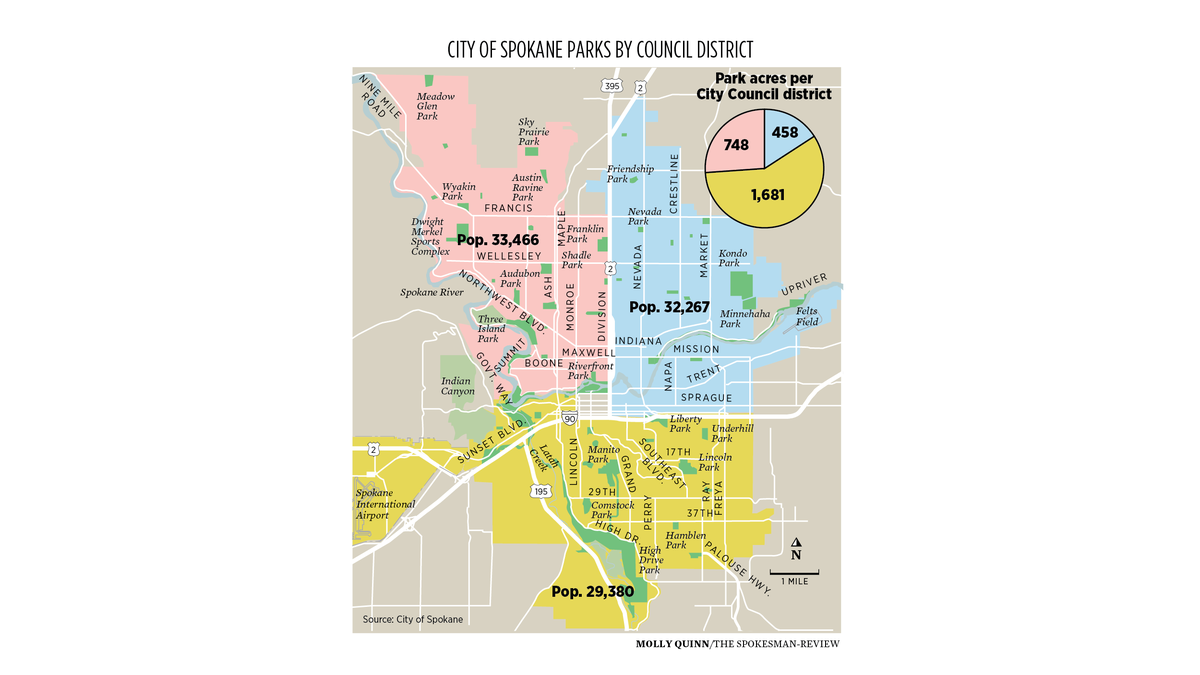

With dog parks, the plan recommends a study to locate up to 10 potential sites for off-leash dog parks citywide. The city presently has only two off-leash public dog parks, both within the city council district that represents south Spokane: The Downtown Spokane Dog Park on Riverside Avenue and the SpokAnimal Dog Park in High Bridge Park.

Beyond the new additions, the plan places an emphasis on restoring parks like Minnehaha that are in failing or poor conditions – namely, Courtland Park, Liberty Park, Grant Park, Summit Boulevard Parkway, North Maple Street Parkway and Logan Peace Park.

Another objective identified in the plan, as driven by community feedback, is updating and adding new parks facilities, such as restrooms, trails, trailheads, fishing areas and bike-skate parks within the northeast city council district and water access for kayaking, fishing and other activities.

In determining where to locate new parks and restore existing ones, the draft plan looked at equity gaps and underserved areas and populations that “don’t benefit as much” from the parks system as other parts of Spokane, Laybourn said.

“The city has really invested in some of its incredible signature parks in the past,” Laybourn said. “What we’ve learned from the community is the desire to upgrade the older or overlooked parks that are a focus of everyday life, and that’s going to require some additional funding the city doesn’t have.”

Like other plan elements, a focus on homelessness within the plan was driven by community feedback while the issue has been at the local and national forefront for some time, Jones said.

One of the master plan’s goals is to address the role and the policies of Parks and Recreation in working in partnership with other city departments and agencies with addressing homelessness concerns. According to the draft plan, parks departments nationwide vary in addressing homelessness. Some, for instance, partner with organizations serving the homeless, and others sanction encampments.

As Parks employees often interact with homeless individuals, one of the plan’s proposed strategies to this end include trauma-informed training for frontline staff members.

People who experience homelessness depend on park spaces for their survival, Laybourn said.

“I really would love to see Spokane be smarter than a lot of other cities in getting ahead of understanding how to strike that balance between the rights of all people to exist in public space while maintaining a welcoming atmosphere for all park users,” she said. “We gave some strategies and action items within this plan to help the city get ahead of where some other cities are struggling today in helping to create that balance and show a compassionate and effective response.”