Washington coaching legend Jim Lambright’s brain donation pays dividends to CTE research years after death

The brain behind UW’s most dominant defense sits on a black mat in the basement of the Harborview Research and Training Building in downtown Seattle. It has been cut into a series of thin beige slices, some removed to be studied under a microscope.

It is 3:23 p.m. on Friday, May 13, and the Buster Alvord Laboratory for Neuropathology Research is hosting a family reunion.

“This is him,” UW Medicine Division of Neuropathology and Fellowship director C. Dirk Keene says, removing a blue towel to reveal Jim Lambright’s brain.

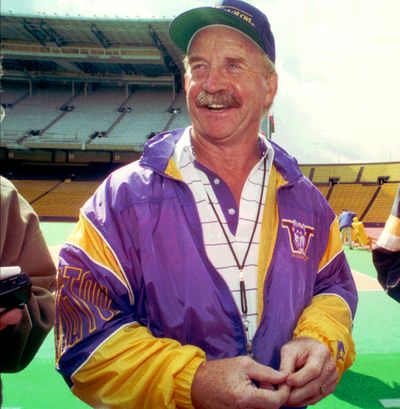

Lambright, of course, is synonymous with Husky football — having participated in more games as a player or coach (386) than any other person in program history. He’s most known for masterminding UW’s defenses under Don James from 1978-92, helping secure six conference titles and the program’s most recent national championship in 1991. He also compiled a 44-25-1 record in six seasons (1993-98) as the Huskies’ coach and earned All-Coast honors as an undersized, undaunted UW defensive end under Jim Owens in 1964.

“He lived and died for the University of Washington,” longtime UW assistant Randy Hart told The Times in 2020.

Lambright died on March 29, 2020, at age 77, following a decadelong battle with dementia. His children, Kris and Eric Lambright, suspected Jim’s deterioration was due to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — a neurodegenerative disease found in former athletes, military veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

“He was knocked unconscious in football multiple times, and who knows how many times he slammed his head into someone else’s, over and over and over,” Eric Lambright said. “And he did it when he was coaching, too, with no helmet on.”

Kris and Eric donated their dad’s brain to the UW Medicine Brain Repository and Integrated Research (BRaIN) laboratory following his death, in hopes it could assist medical research and improve treatment of brain injuries.

The results were not what either expected.

Now, the Lambrights are together again.

In the basement of the Harborview Research and Training Building, Kris and Eric Lambright — both UW alums — stand side by side, wearing matching white masks, before 30 preserved slices of their father’s brain. Dr. Amber Nolan points to a particularly shriveled, spongelike tip dangling from a section of the temporal lobe. This, she explains, is the hippocampus — a region primarily responsible for memory.

When he died, Nolan notes, Lambright’s hippocampus was “probably less than half the size of what we would expect to see in a normal brain.”

In all, the study of Lambright’s brain revealed not just CTE, but four simultaneously converging culprits:

• High stage CTE

• Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurological disorder that causes the brain to atrophy and erodes memory and other mental functions

• Lewy body disease — a form of dementia in which protein deposits develop in the brain’s nerve cells that control thinking, memory and movement

• TDP-43, an abnormal protein commonly associated with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia

Lambright’s case exposes an untidy truth: it’s rarely simply CTE. Nolan says that in “80-90 percent of the cases we have of neurodegenerative disease, there are multiple processes happening. It’s pretty rare that we get pure diseases of one or the other.”

And despite the suspects, it’s unclear what killed him.

The autopsy offers answers and questions alike.

“We got an answer as to why he was struggling, but it also opened our eyes to a larger issue,” Eric Lambright said during a presentation promoting the “BRaIN lab” on April 7. “We don’t know enough to say that CTE was specifically the cause. It could have been Alzheimer’s disease. It could have been Lewy body disease or the TDP-43. We just don’t know. And for a man who had so much pathology and so much neural degeneration, he was actually still functioning at a relatively high level.

“So what we do know is there’s still so much to learn.”

· · ·

Until the day he died, Eric Lambright says, his dad “could tell you the details of the USC game in 1984.”

(It was a 16-7 outlier loss in an otherwise sparkling 11-1 season.)

He was a walking encyclopedia of Husky history.

But elsewhere, his cognition began to decay. In the decade before his death, Lambright struggled with short-term memory. Unbeknown to his children, he eventually stopped brushing his teeth. He’d frequently get lost while driving, which prompted Eric and Kris to take away his car in early 2019.

“Dad was known for his fiery temper on the football field, and it definitely came out when he could no longer drive,” Kris Lambright said in a presentation April 7. “Both Eric and I bore the brunt of that at times. He even got mad and tried to argue with a neurologist on two different visits about why he was still capable of driving. Because even driving was like a competition to him, where he always wanted to win.”

Increasingly, Lambright could no longer compete — which prompted an eruption of angry outbursts. Eric said “there were days when both Kris and I got 15 to 20 voicemails, back to back to back to back to back. It was all essentially the same content, but with different vulgarities and emphasis on things.”

Added Kris Lambright: “As Dad’s dementia worsened, it meant I had to become a parent to my parent, and that part was really hard.”

After being moved to a memory care center, Lambright — who didn’t believe he belonged — twice attempted to escape: first by stacking lawn furniture and scaling a fence, then by wheeling a gas grill to the same fence and repeating the feat.

“So then we get there, and it’s his fault; there’s no lawn furniture anywhere,” Eric Lambright said.

Of course, Eric and Kris know now that their dad was contending with invisible enemies.

But the brain behind UW’s most dominant defense didn’t completely diminish. Even in Lambright’s final years, Eric loved talking on the phone with his dad during football games. “He just loved football, and he loved to talk about it, and he was so good at seeing the whole field,” marveled Eric, a former walk-on defensive back who played for his dad at UW in the 1980s.

Likewise, Kris bonded with her father through Mariners baseball. She had her dad over for dinner once a week, and “we’d just sit and watch the game and have some dinner and talk baseball, so often that he would text me other nights, ‘Did you see the end of the game? Are you watching?’”

And not all of Lambright’s behavior is so easily explained. In the final months of his life, his attention span rapidly disintegrated … except when it came to coloring books. A man former UW outside linebacker and assistant coach Ikaika Malloe called “one of the toughest guys I ever met” would cut photos out of magazines and tape them up, then color on the wall.

“It was almost childlike,” Eric Lambright said. “He would be fascinated by the florist department (at Fred Meyer). He’d be talking about the colors, like a young kid would. So we walked into the art aisles, and he’s always loved animals. He started looking at these coloring books, and I was like, ‘Would you like a coloring book?’ He was like, ‘Oh, I’d love that.’ So we got coloring books and colored pencils and markers. I think I just got him one at first, and he finished it in just a couple days. He loved doing that. It occupied him. It was this kind of sweet, simple pleasure.

“I don’t know what that was. We still don’t really know why he died.”

They do know that the anger and the erratic behavior — that wasn’t their dad.

Before he died, the disease was driving.

“He had a lot of bad things happening in his brain,” Keene said, addressing Kris and Eric from across a table inside the Harborview Research and Training Building. “I think you can be confident that what was going on in his brain was causing that (behavior), and not him.”

He paused, then added: “He was fighting the good fight.”

· · ·

Even now, the fight isn’t finished.

Roughly 176 Americans died from a traumatic brain injury each day in 2020, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). There were more than 223,000 TBI-related hospitalizations in 2019, while 15% of all U.S. high-school students self-reported one or more concussions that year.

At the UW Medicine “BRaIN lab” Keene acknowledges that “TBI comes in many flavors. We think a lot about CTE in sports. But the reality is that TBI can happen in many different ways.”

But more work must be done. In addition to their efforts, the “BRaIN lab” shared more than 8,000 brain samples with researchers around the world in 2021. The ultimate goal is to develop systems to diagnose and treat traumatic brain injuries before a person has died.

To do that, UW Medicine’s “BRaIN lab” and other research centers like it need more brains — healthy brains, damaged brains, brains of every age and nationality and socioeconomic background.

Keene estimated that UW Medicine has roughly 4,000 brains.

It’s not nearly enough.

“The brain represents who a person is, everything about that person, everything that person has experienced and thought and felt,” Keene said. “To give that as a gift to research is the greatest gift I think anyone can give.”

The experience has given Kris and Eric Lambright a different kind of gift. In the six months since they received the results, it has allowed them to process their dad’s decadelong battle with a more profound perspective.

“It breaks my heart to know that Dad was having to overcome so much just to try to function normally,” Eric Lambright said April 7, choking back tears. “But it did, however, hammer home the importance of giving people grace when we don’t know the cause of their behavior.

“Dad was a challenge, to say the least. But since we knew that CTE was likely, it helped us to respond with patience and love, and I’ll always be thankful for that.”

For the Lambrights, specifically, the fight goes on. Eric added on May 13 that “We’re going to keep trying to figure out how we can continue to help.” Samples of Jim Lambright’s brain will be used in studies and research for decades.

He lived and died — literally — for the University of Washington.

“When (Keene) asked if we’d also want to donate his body to the autopsy center at UW, I just thought about how much this man loved all things University of Washington,” Eric Lambright said. “So the fact that his body might be laying out in different parts of the school, for me that seemed really cool. I think he would have just freaking loved that.”

He also freaking loved his family.

“When things were good, he was a really loving, kind man,” Eric added. “You knew that he loved you.”

It’s 3:47 p.m. on Friday, May 13, and the family reunion is almost over. Kris and Eric Lambright shuffle slowly to the exit of the Buster Alvord Laboratory, leaving their father’s brain behind.

Before they go, Eric turns to the 30 assorted samples.

“See ya later, Dad,” he says.