This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Spin Control: Support it or not, but protesting at a judge’s home is not a new tactic

A U.S. Supreme Court police officer stands outside the home of Justice Samuel Alito on Thursday, May 5, 2022, in Alexandria, Va. A draft opinion suggests the U.S. Supreme Court could be poised to overturn the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade case that legalized abortion nationwide, according to a Politico report released Monday. Whatever the outcome, the Politico report represents an extremely rare breach of the court's secretive deliberation process, and on a case of surpassing importance. (Kevin Wolf)

While the Founding Fathers enshrined the right to “peaceably assemble to petition the government for a redress of grievances” in the Bill of Rights, they did not define peaceably.

That means almost any assembly beyond a few people standing mute and burning candles – if it is for a redress that other people don’t consider a legitimate grievance – will generate criticism if not outright condemnation.

Take for example the picketing of judges handling a case involving the polarized sides in the abortion debate. When those unhappy with a pending decision gather outside the home of a jurist, those who are apt to be happy with the decision are quick to say the protesters are stepping outside the bounds of propriety, trying to unfairly influence the outcome of the case and possibly guilty of harassment.

That’s what one hears from some abortion opponents, who have been quick to criticize the protests outside the homes of Supreme Court justices pondering the fate of the landmark Roe v. Wade in the wake of a draft opinion leaked earlier this month. Some abortion rights supporters, however, are applauding those protests as an exercise of First Amendment rights.

Before local activists take a hard and fast stand on the current protests, however, they might want to think back to 1985, when the sides were reversed and abortion opponents were the ones picketing a judge whose ruling restricting their protests in front of a Spokane medical facility and jailing demonstrators who repeatedly violated his injunction.

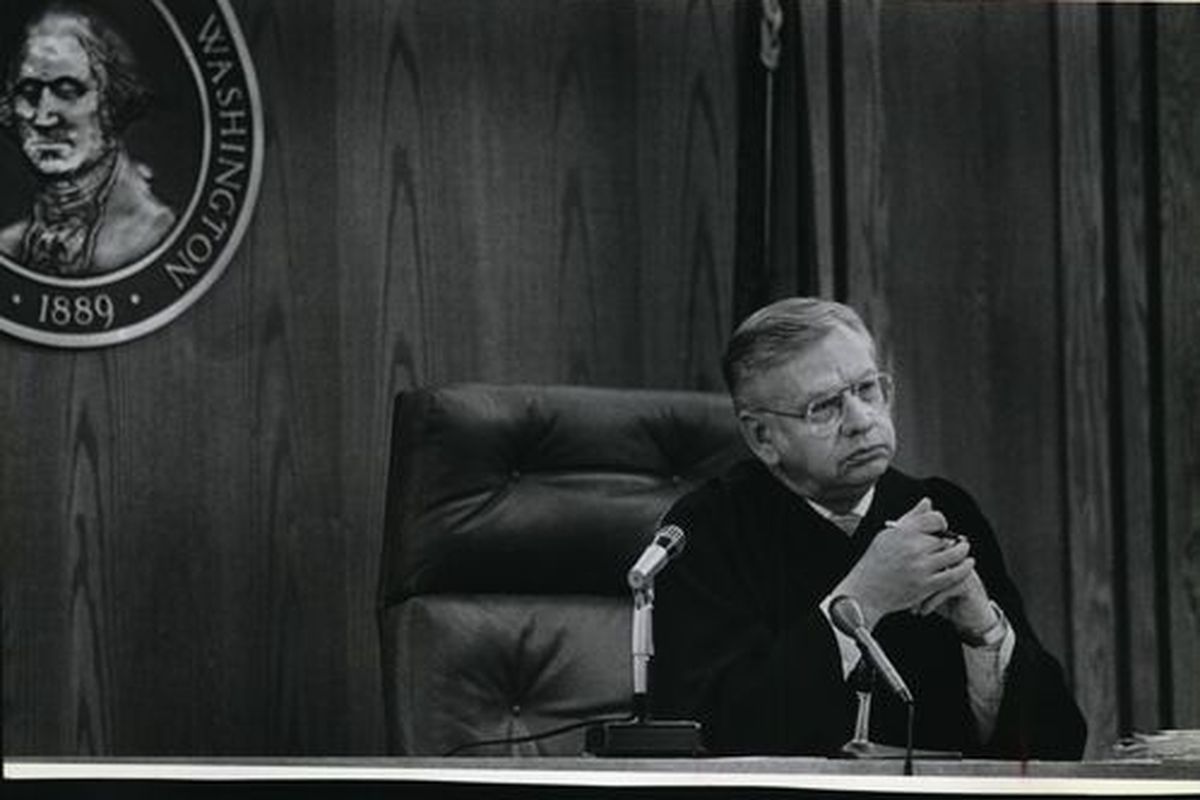

Superior Court Judge Willard Zellmer was a Lincoln County jurist who regularly helped out in Spokane as a visiting judge when the local dockets got full. He was unlucky enough to draw the case of doctors in the Sixth Avenue Medical Building who asked for a court order against the ongoing protests of Share, a local anti-abortion group that had been picketing off and on for months in front of the building. What they called “counseling” of people approaching the building, others called harassment. During heavy snows of February and March, the protesters were filling the shoveled sidewalk and blocking easy ingress to the building. After a couple of days of hearings, Zellmer came up with an order that restricted the protesters to the sidewalk along Stevens Street or across the street from the entrance.

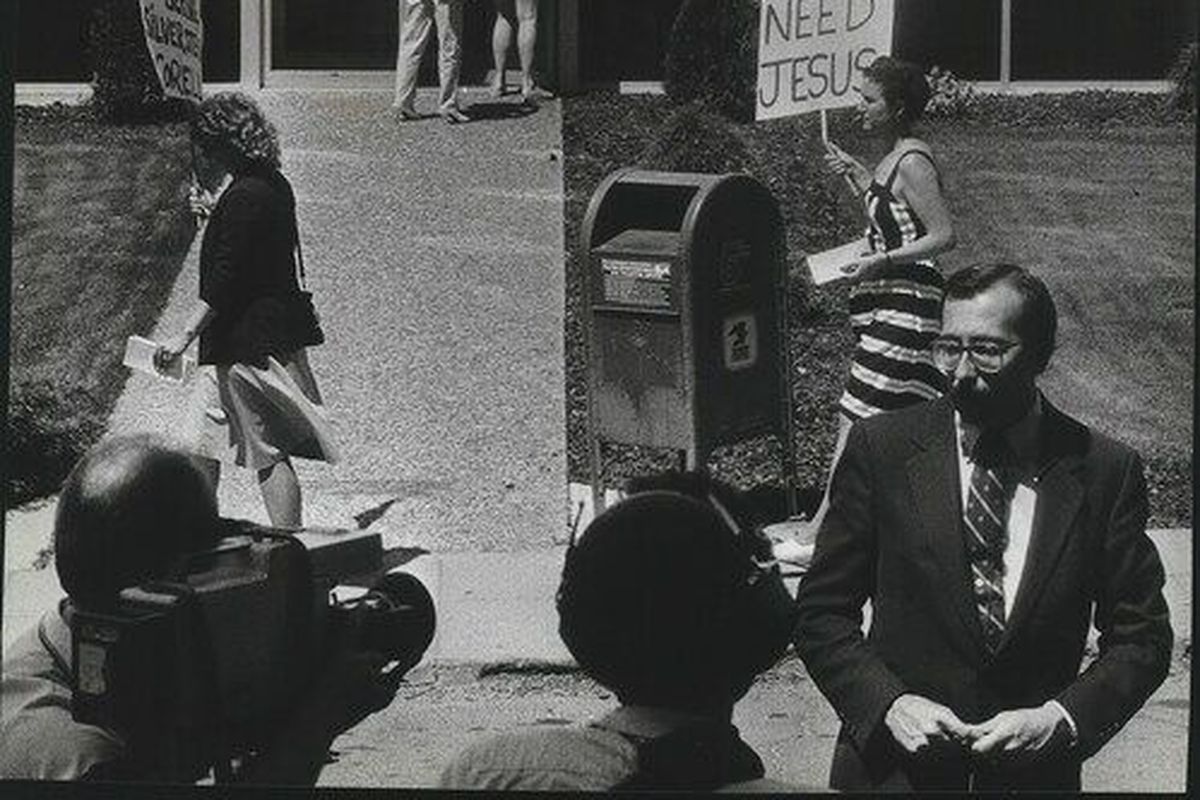

For a few weeks, Spokane was the white-hot center of the anti-abortion movement, with national figures coming to town to denounce the injunction and inspire followers. Some protesters obeyed the rules of the injunction, others did not and were cited for contempt.

Protesters then expanded their activities, traveling to Davenport to picket outside of Zellmer’s home, as well as picketing outside the home of Dr. Stacie Bering, the obstetrician whose name is on the case, Bering vs. Share.

If they hoped to influence the case or bring public opprobrium on their targets, they pretty much struck out.

Although one of Zellmer’s neighbors yelled at the protesters to leave, the judge, who died in 2013, said they were within their First Amendment rights. He talked for a while with the protesters, who included one of the women he ordered jailed for disobeying the injunction, and at one point took pictures for his scrapbook. He told a reporter he was “somewhat disturbed” by the personal nature of the protest but added public officials are subject to such scrutiny.

“They have a right to do what they are doing,” he said at the time.

Bering’s neighbors came out onto their front lawns in a sign of solidarity with her and her family.

Zellmer didn’t relent, and the injunction remained in place.

Three of the protesters were repeatedly cited for civil contempt for violating the rules at the medical building. Attorneys for Share appealed the injunction to the state Supreme Court, which upheld Zellmer’s ruling. The three were charged with criminal contempt; one was convicted but two were acquitted.

The whole process took more than a year. Throughout that time, people in Spokane on both sides of the abortion issue debated the limits of free speech and peaceable assembly. Echoes of that debate can be heard in the more recent legal battle over protests outside of Planned Parenthood, which have strained any definition of “peaceably” with high decibel levels of their gatherings and allegations of harassment of patients and staff.

It may be too much to suggest that Chief Justice John Roberts or Justices Samuel Alito or Brett Kavanaugh follow Zellmer’s example and come out with a camera or try to engage with the protesters. The U.S. marshals providing their security would likely veto that, even were they so inclined.

Although the level of the court system, not to mention the overall stakes in the abortion debate, are higher, consistency would suggest that anti-abortion foes who thought protests outside Zellmer’s home were a reasonable tactic should support the same outside the homes of Roberts, Alito and Kavanaugh. Abortion rights advocates who thought the Share protesters should have stayed home and let the justice system play out should have the same advice for the current demonstrators.