Wide learning gains: Teacher uses tech tools that measure real-time students’ skills, offset pandemic education loss

Melva Pryor, an elementary school teacher at Skyline Elementary, center, smiles as she helps her students through a lesson as a group works from laptops in the foreground on April 29 at Skyline Elementary. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

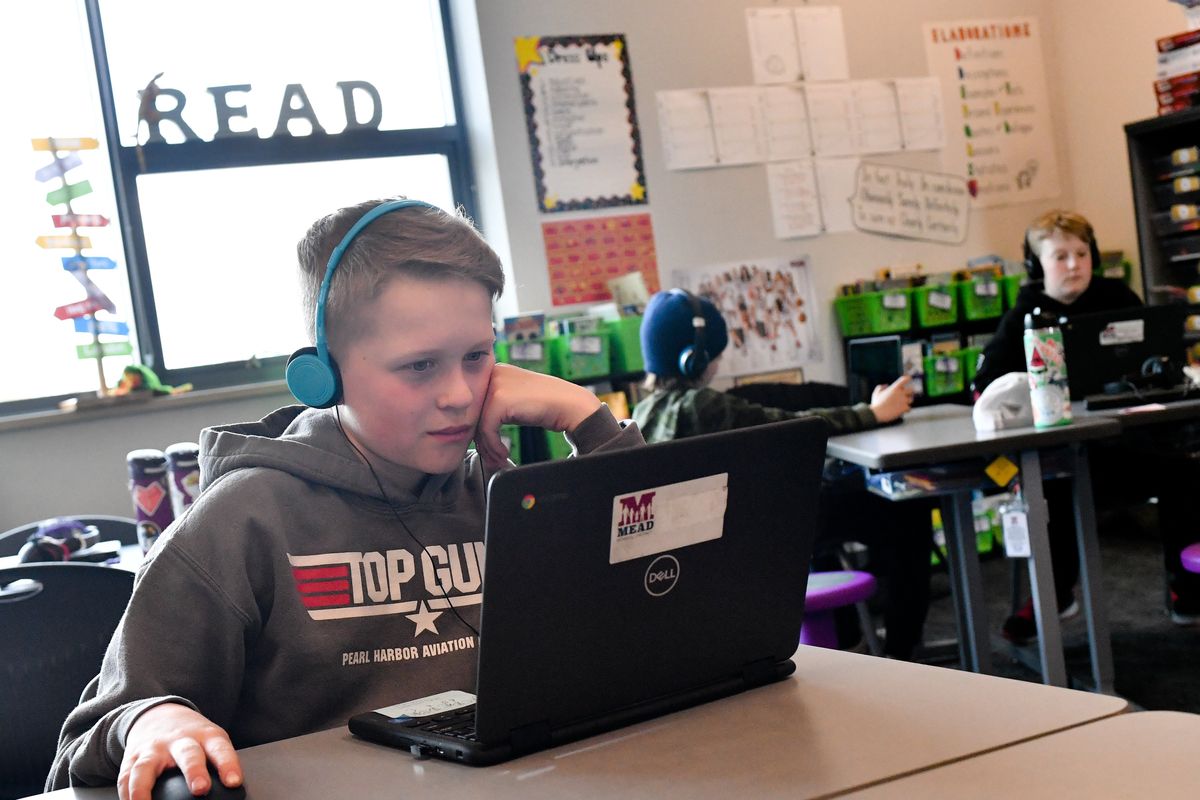

Technology tools for students accelerated during the pandemic. Despite often a bad rap about kids on computers, one longtime Mead teacher has noticed wide learning gains this year among her fourth-graders.

Skyline Elementary School teacher Melva Pryor said her students are each assigned a Chromebook laptop – a school district investment last year when Mead had in-person classes – yet flexible to go remote if COVID-19 cases rose. Again this year, students are using the laptops and tools such as Google Classroom, Lexia Learning and Prodigy.

Pryor, a 34-year educator, said she sees many positives as a result of this shift since fall 2020. The technology is allowing her and other educators to see real-time data, daily, on students’ skills that might need individualized teacher support, or let some children leap ahead. The feedback helps her adjust to student needs far ahead of state testing assessments, she said. The Chromebooks go home with students, who bring them back to school.

However, her students while at school aren’t constantly on their laptops, Pryor added. She blends in overall classroom instruction, group-learning rotations and hands-on work.

“Last year, when we were face-to-face, we would never know if we were going to be in-person or if we would have the number of cases that would cause us to shut down,” Pryor said. “So, the students would take the Chromebook back and forth, and we taught them to use platforms like Google Classroom, Lexia, Raz-Kids and all the things we wanted them to do, if we had to go virtual.”

The option this year also helps if students miss school days. Today, Pryor said she wouldn’t want to go back to a less-tech classroom as before, for her students’ sake.

“With the one-on-one Chromebook, I’m able to use the technology as a way to differentiate for my students because they are coming from different places,” Pryor said.

“Platforms like Lexia allow me to have real-time data that I can use to make decisions around teaching about flexible grouping with small groups, and one-on-one, I can address needs right away.

“I know where my students are performing, and it will tell me what skills my student is working on, what errors they’re making. I can say, ‘Oh, I noticed you’re having some trouble with idioms, can you come back and work with me?’ Then we can go through it, and I can teach that skill, and they’re able to move on.”

As another example, another student hadn’t grasped elements of reading comprehension and text structure, so she worked with the child one-on-one on the concepts.

It’s been a steep technology learning curve for her. Pryor has spent most of her career at Mead, other than a stint 2015-18 at Spokane International Academy, a K-12 charter public school, where more technology was used in classrooms. One of her jobs there was curriculum director.

Pryor missed teaching kids directly and returned to Mead in 2019 with first-graders until the pandemic shut schools down. The 2020-21 Mead school year stayed in-person, with masks and protocols. But families had the option of virtual learning, so some students in class this year did remote-only, while others moved from outside the region.

The newly constructed Skyline opened this past fall. Previously in Mead, Pryor said she and other teachers shared a cart of computers for technology learning for short times each day. It wasn’t unusual for many schools then because of the expense, she said.

“The pandemic forced advances in technology because we needed to help our students continue to move forward.”

A student’s Chromebook is assigned for a number of years, she said. Pryor can integrate technology and assignments while each can get a “what I need” approach, she said.

“I feel it just helps kids feel better about where they’re at and also to take charge of their own learning because we really set a lot of goals in the classroom, and they know, like on Lexia, ‘I need to make this number of units and finish this much time in order to be on grade level by the end of the year.’ It empowers them.”

She can receive information on each child’s needs or work to offset any learning losses from pandemic shutdowns. “For me right now, I want to know in the moment where students are having trouble so I can help them out and individually because they’re all unique.”

That’s both on and off their devices. Often during a school day, students are interacting with her and classmates. There’s a morning meeting and work with specialists. Math involves a whole-class lesson for core instruction, followed by three rotations.

One rotation is doing a Zearn lesson, complementing the math curriculum. Another rotation applies Prodigy, a program that can shore up skills that students missed.

A third rotation with Pryor has project-based learning or hands-on manipulatives, “so I can reinforce concepts that we’re learning in class.” There’s time to practice by playing math games, such as for multiplication and division.

After lunch, students work on English language arts for reading and writing, again starting with full classroom instruction. The ELA rotations follow, such as working with Lexia that enables students to work on goals by week’s end. The students close to meeting grade-level targets might need to do 20 minutes of work, while other students complete longer stretches to reach goals.

“All of my students have made significant growth,” she said. “There are quite a few of them who have made over a year’s growth on Lexia. There were some who are already on grade level. They’ve completed the fourth-grade core skills and now are working on fifth-grade skills.”

One student has finished fifth-grade skills. In another rotation, Pryor works with a group of students. A third rotation has them reading or listening to books.

“I really want my kids to love to read, so we’re working on just reading books on that last rotation, or if using Epic, they can listen to books.” After recess, science lessons are mostly hands-on, and then social studies work. Technology can boost social studies’ access to articles, she said, to listen to text or read.

“I feel there are some real positives and enhancements that have come out of this that have really made me be a more successful teacher,” Pryor said. “Again, my kids are not on the Chromebook all the time, but there is a time where they get to work on their level, uninterrupted. They put their little headphones on, and they just get to work.

“They get to do it at their own pace. They get to advocate for themselves and say, ‘I need help with this.’ I can swoop in before that little quiet kiddo slips between the cracks.”