‘Something you never, ever get through’: Half a century ago in the Silver Valley, 91 Sunshine miners died in Idaho’s worst mining disaster

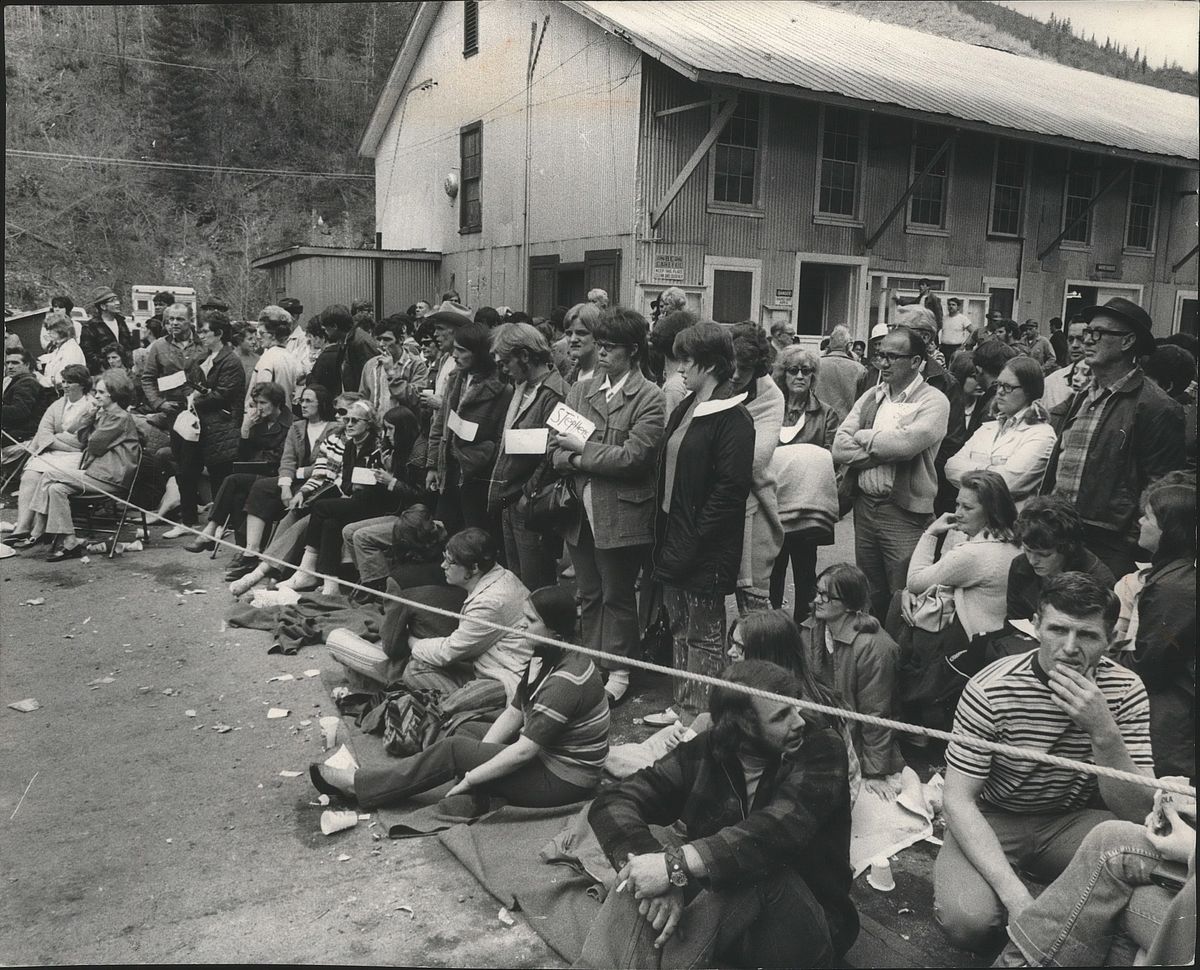

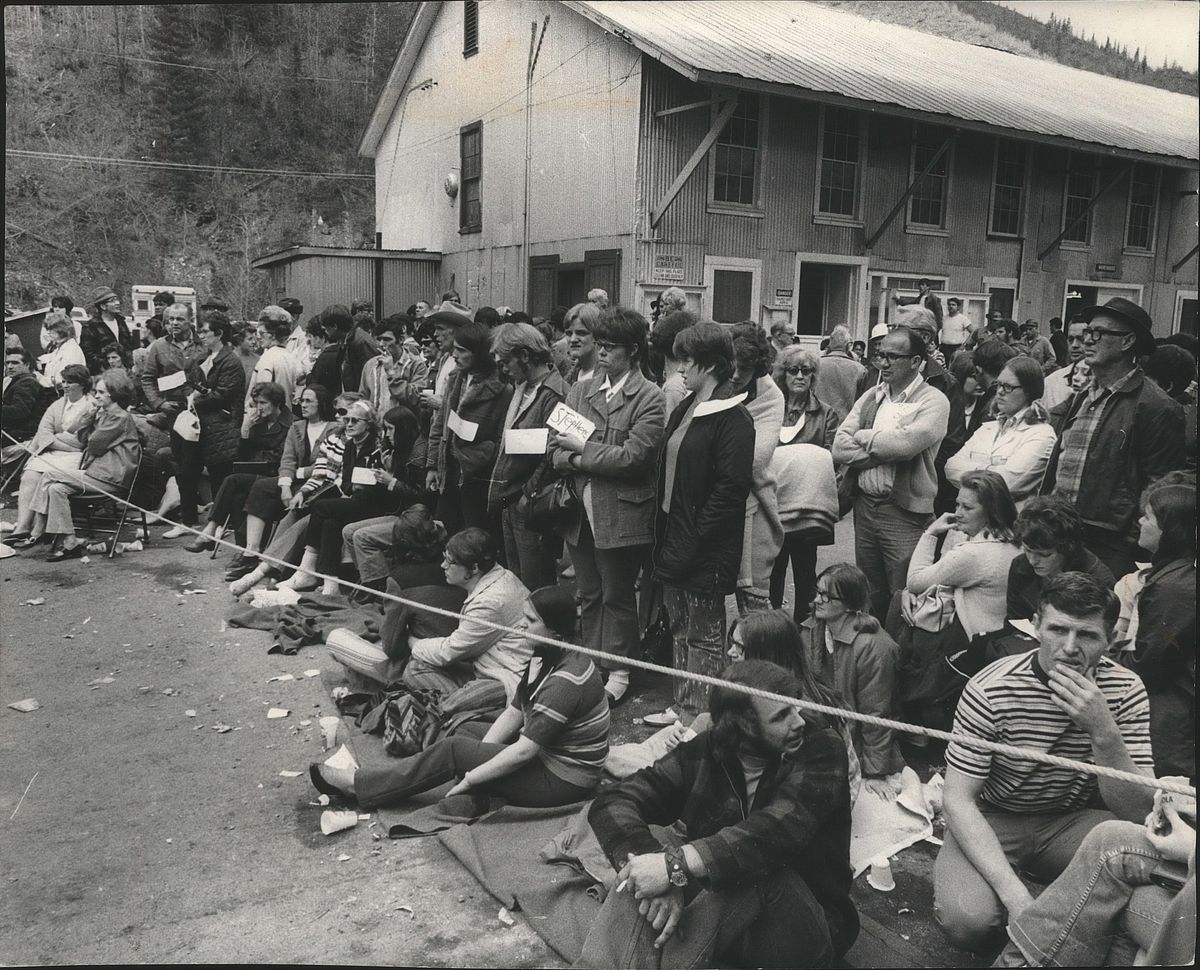

A crowd waits outside the Sunshine Mine for updates from the accident in May 1972. (Spokesman-Review photo archives)Buy a print of this photo

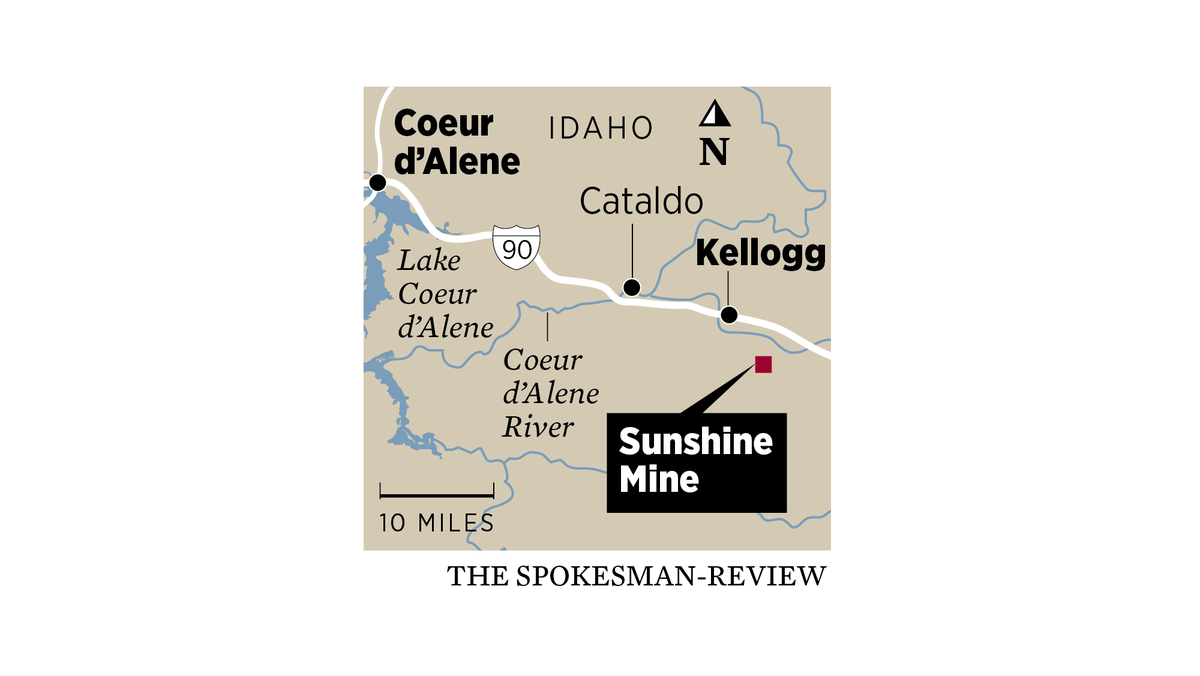

The Sunshine Mine Disaster still reverberates across North Idaho’s Silver Valley half a century after that fateful day in 1972 when 91 miners died from a fire and smoke underground.

“It’s hard to believe because it seems like it was just yesterday,” said Peggy White, 70. She lost her father, uncle and brother-in-law in the tragedy.

The fire led to sweeping mine safety reforms. It left 217 children fatherless and devastated the community.

“It’s something you never, ever get through,” White said.

Typical day turned tragic

In the early morning of May 2, 1972 as the night crew headed home, 173 miners arrived for their shift in the “deepest and richest silver mine in the nation,” according to a Spokesman-Review story at the time.

The miners began to notice smoke just before noon, which wasn’t uncommon in the mine. But as the smoke thickened, it became clear something was wrong.

Miners began trying to make their way up through the maze of mine shafts.

What they didn’t know was that the fire was near a part of the mine where clean air came in, causing carbon monoxide to circulate through the main airways.

Most miners hadn’t been trained to use the rebreathers stocked near the first aid kits by their work areas.

Those would provide them with a limited amount of breathable air, according to news articles at the time. Some tried to wet their shirts and breathe through them, hoping to block out the smoke, unaware that carbon monoxide was the real threat.

A crowd awaits outside the Sunshine Mine as rescue efforts continued in May 1972. (Cowles Publishing)

Dozens of miners were able to escape, thanks to the courage and skill of the lift operators who went deeper into the mine to pick up their fellow miners.

Byron L. Schulz was a 21-year-old “cager” who helped get the 56 miners who escaped to safety. From the hospital bed where he was being treated for smoke inhalation the day after the fire, Schulz told Spokane Daily Chronicle reporter Bill Morlin of his harrowing escape .

“I was pulling the cage at the 5,600-foot level when the buzzer went – oh, I’d say about 11:30 or so – I went to the 3,700-foot level. It was filled with smoke but I couldn’t see any fire,” Schulz said. “I loaded up some men and took them up to 3,100 so they could walk out.”

Schulz went back down into the mine, deeper this time, to get more men.

“When I came up the last time, I couldn’t go back. Before I headed up, I went into the hoist room,” Schulz said. “When I came out there, all these guys were laying around gasping for air. I felt some pulses and some guys were dead at that time.”

After making it out of the danger zone, Schulz had to walk a mile up another tunnel to the Jewel shaft, where he was hoisted to safety.

“I started walking, and I knew I was about ready to go when the rescue crew picked me up and gave me oxygen,” Schulz said. “If they hadn’t picked me up, I would never have made it.”

Schulz became emotional when talking about the hectic escape.

“If they had just been more organized, there wouldn’t be 58 men down there. Everybody was just in an uproar,” he said. “There was no organization – nobody knew what to do or how to do it.”

By late that first night, 24 people were known to be dead and 58 remained missing, according to a May 3, 1972, Spokesman-Review article.

Initial rescue crews said the mine was “extremely hot, extremely smoky and almost impossible to see in.”

Relatives of the trapped miners held a vigil near the mine’s main shaft. Idaho Governor Cecil Andrus arrived on scene the next day.

“The only thing in our minds right now is the rescue of any survivors,” Andrus said at the time. “I’m convinced right now that everything is being done which can be done.”

Fresh air was forced through the mine in hopes that the missing miners were still alive.

A day after the fire broke out, the incident was already being called “the worst disaster in Idaho mining history,” according to a Spokane Daily Chronicle story.

Marvin Chase, vice president and general manager of Sunshine Mining Company, said at the time that hope remained the missing men were alive.

Two days after the fire, President Richard Nixon asked the Federal Bureau of Mines to investigate . On May 5, it came to light that many miners hadn’t been trained to use the individual air resuscitators that could have protected them from the smoke and toxic gas.

On May 7, rescuers discovered more bodies, bringing the death toll to 35.

Miners who had escaped began sharing their safety concerns.

“There better be some improvements or there won’t be any miners in that mine,” William Mitchell, a 26-year-old, told The Spokesman-Review.

“They better have better safety equipment.”

The first funerals for miners whose bodies had been recovered began taking place as rescue efforts continued.

Lee Donald Beehner, 38, escaped the mine but returned to try and save his friends. Reports indicated Beehner removed his air mask and thrust it onto the face of a fellow miner. The two died side by side.

“He died trying to save a fellow miner,” Pastor Ralph Wendt said at Beehner’s funeral.

A slew of mechanical malfunctions complicated rescue efforts, including a break in a major electrical cable that had to be repaired for work to continue.

After a week of rescue efforts, hope waned. Five more miners were discovered, bringing the death toll to 40.

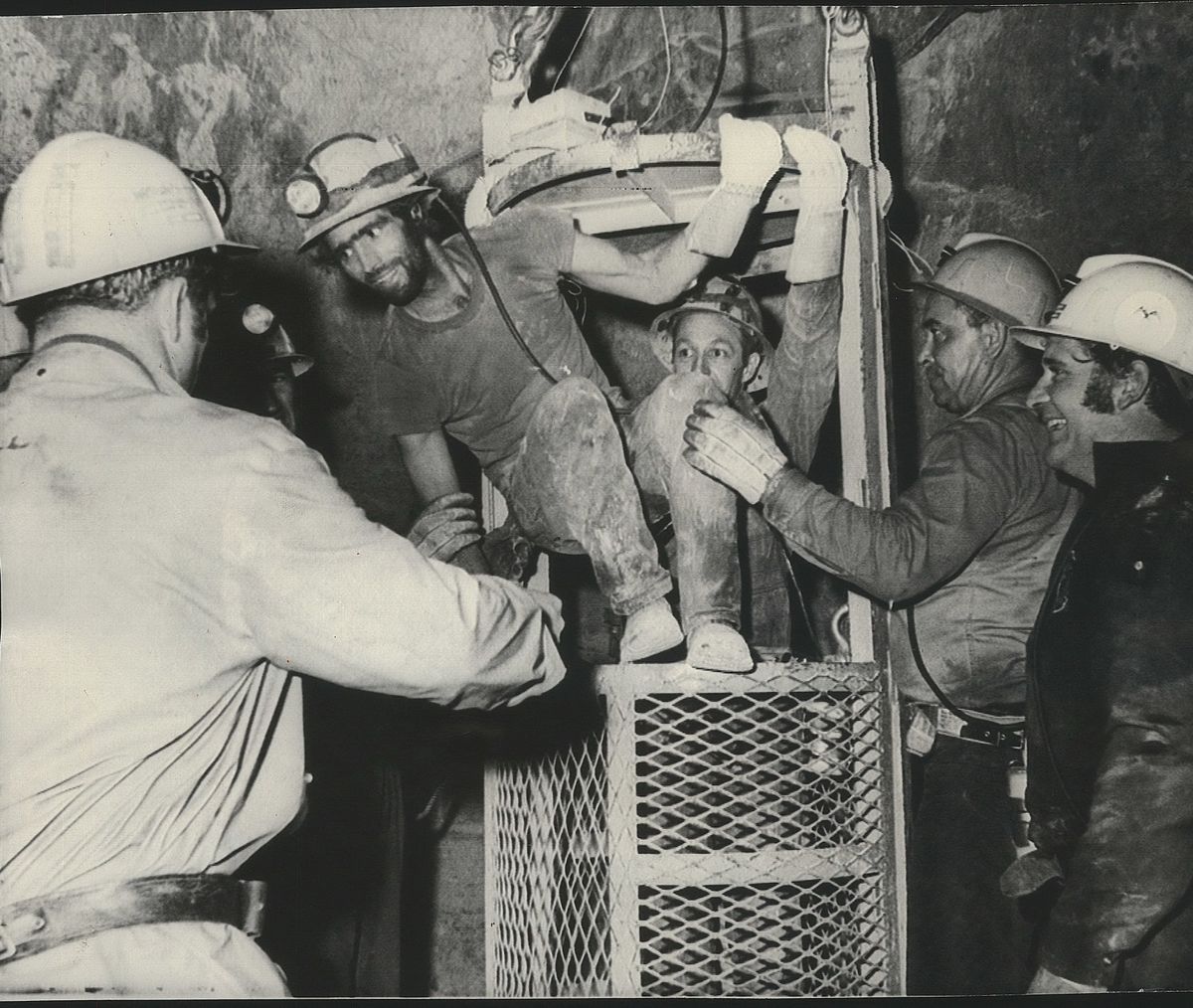

And then two miners, Tom Wilkinson, 29, and Ron Flory, 28, were found alive deep in the mine.

The pair walked out of the mine, “apparently unharmed,” according to a Spokesman-Review story. They were “smiling victoriously” as they pushed aside stretchers and “walked triumphantly away from the scene of their ordeal,” the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported.

The two miners had holed up in a storage room, surviving on their own packed lunches and the lunches of men who had died nearby. When one of them got down, they pumped each other up, they recounted.

“It was the will of God,” Wilkinson said. The survival of Wilkinson and Flory gave families of the missing men hope.

But that was quickly dashed when the last of the miners were found dead on May 12. The dead ranged in age from 20 to 61.

The damage was immeasurable.

Lasting legacy

The cause of the fire was never determined. The mine remained closed for seven months .

A Bureau of Mines report on the disaster listed nine major factors contributing to its severity, including delay in evacuation, failure of company officials to train their miners in self-rescue and survival techniques, lack of evacuation drills and a ventilation system that contaminated the main intake airways with smoke and carbon monoxide.

The tragedy resulted in broad safety reforms in the mining industry. In 1977, the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act passed in Congress, requiring multiple annual inspections of underground mines, strengthened and expanded rights for miners, and required training and mine rescue teams.

A film titled “You are my Sunshine” produced by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in 2002 commemorated the miners lost while also serving as a training video for mine rescue crews. The film now serves as a way to teach the next generation about the tragedy, White said. Last week, students at Kellogg schools watched the movie ahead of the anniversary, she said.

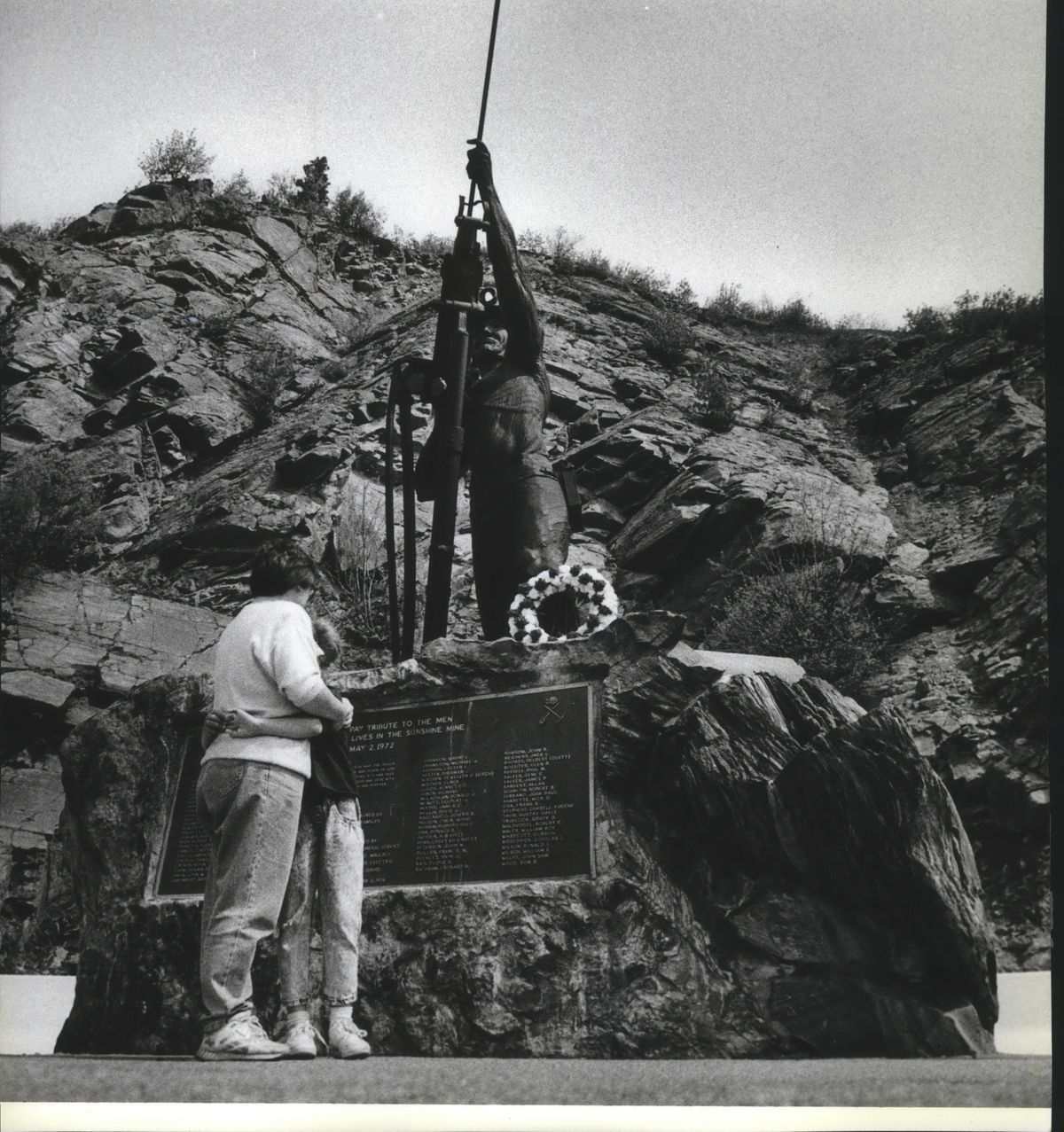

Monday will be the first annual “Miners Memorial Day” after the Idaho State Legislature passed a bill designating the day earlier this year.

Families of those lost planned an anniversary event at 11 a.m. at the Sunshine Miners Memorial located immediately off Interstate 90 at Exit 54 in Big Creek.

White and other community members have been preparing the Sunshine Miners Memorial for the big day. A new sidewalk was installed, new headstones were ordered and the vegetation trimmed.

At the 50th anniversary ceremony Monday, students will sit in chairs with miners’ hats and turn off the lights as the victims’ names are read, White said.

Gov. Brad Little will speak, and families of those lost will have a chance to reconnect and visit, she said.

“That’s why we have it,” White said, “for the families.”