‘The Godfather’ retains its mythic power 50 years after release

What’s there to say about “The Godfather” that hasn’t been said hundreds of times before?

Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel, which premiered 50 years ago this week, is a watershed in American culture. It’s an institution. A milestone. A best picture Oscar winner. A sacred cinematic text. Its greatness is practically sacrosanct.

The film has been referenced, spoofed and imitated over and over again, and yet its effect hasn’t diminished. Countless Mafia films may have preceded and followed it, but “The Godfather” (along with its 1974 sequel) remains the gold standard because it’s both an ambitious, visionary piece of filmmaking and solidly crafted mainstream entertainment. As Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker back in 1972, it’s “a great example of how the best popular movies come out of a merger of commerce and art.”

Even if you were to discount its artistic bona fides, “The Godfather” would still be a fascinating cultural artifact. The details of its circuitous journey from page to screen are themselves inherently dramatic – how Puzo sold the film rights to his then-unfinished manuscript to pay off gambling debts; how 31-year-old Coppola declined the gig but then acquiesced to pay off studio debts; how Paramount Studios head Robert Evans fought to maintain Coppola’s riskiest directorial decisions, including a three-hour runtime and a cast that included a mostly unknown Al Pacino and a washed-up Marlon Brando. (All of this is set to be dramatized in the upcoming miniseries “The Offer,” debuting April 28 on Paramount+.)

The film’s story begins in the waning months of WWII and spans a decade in the lives of the Corleones, the most powerful of New York’s five primary crime families. When aging patriarch Don Vito (Brando) is nearly assassinated by a rival crime family, his three sons – impetuous Sonny (James Caan), feeble Fredo (John Cazale), virtuous Michael (Pacino) – step in to maintain the Corleones’ foothold.

It’s Michael, the prodigal son who has returned from fighting overseas and initially distances himself from the family business, who becomes the moral center of the story. The movie isn’t really about Mafia murders and brutality; it’s about a good man’s inevitable corruption, about his struggle to maintain the purity of his soul, about the need for vengeance ultimately overtaking him.

When “The Godfather” was released, movie studios were still reeling from a string of old-fashioned, big-budget flops, and audiences were gravitating toward grittier, edgier, more socially relevant pictures: “Bonnie & Clyde,” “Midnight Cowboy,” “Easy Rider,” “The French Connection.” In that sense, “The Godfather” was accidentally symbolic of its era’s film landscape, straddling the line between the grand sweep of old Hollywood and the cynicism and violence of new Hollywood.

“The Godfather” eventually surpassed 1965’s “The Sound of Music,” the sort of family-friendly spectacle on which studios had for so long relied, to become the highest-grossing film of all time. It was also critically adored in a way that massive blockbusters rarely are: The New York Times’ Vincent Canby said it was “as dark and ominous a reflection of certain aspects of American life as has ever been presented in a movie designed as sheer entertainment.”

Much of its dialogue has entered the lexicon – whom amongst us hasn’t made a joke about making someone an offer they can’t refuse? – and its young actors became superstars overnight.

Puzo’s 1969 novel is propulsive pulp, but Coppola’s adaptation is so shrewd because he streamlines the material, honing in on the most interesting characters and cutting many of the book’s baggiest (and weirdest) subplots. The novel details the rituals and hierarchies of the Corleones’ hermetically sealed world with a flat, journalistic specificity, but Coppola found a way to imbue that material with a sense of pain and loss that’s missing from Puzo’s prose.

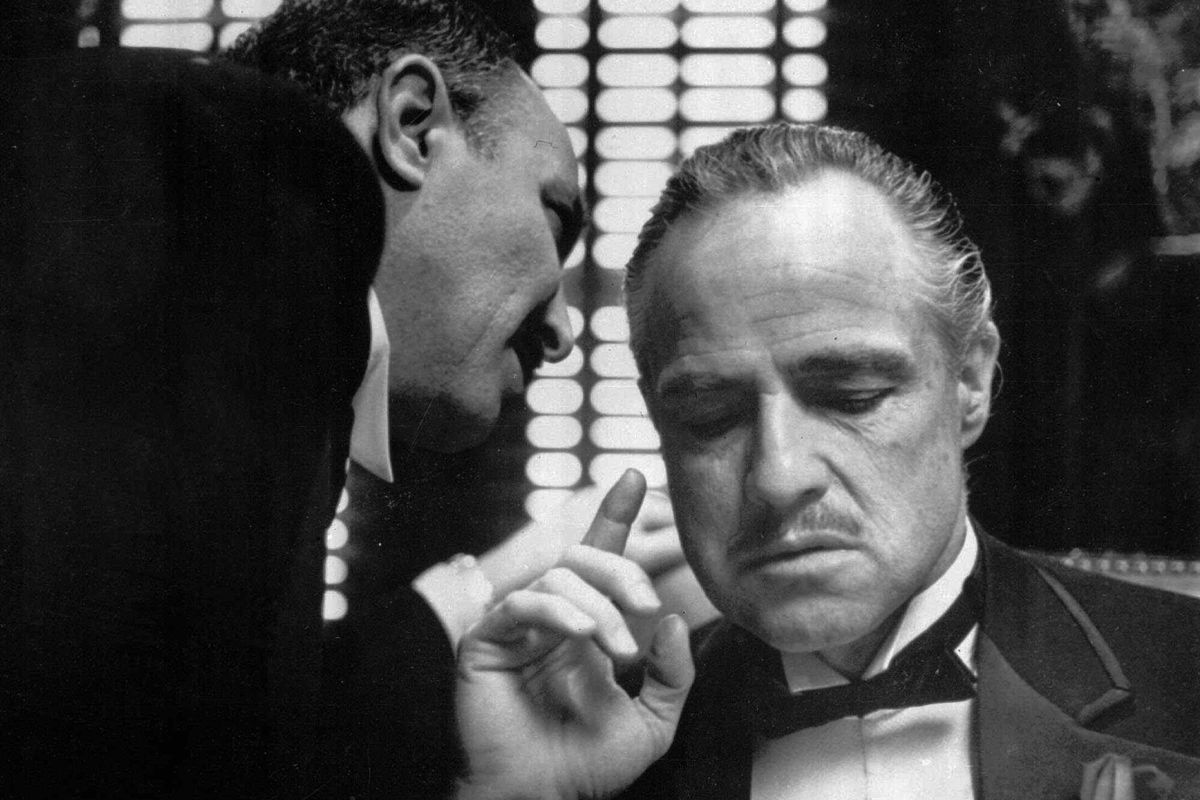

Seeing the film’s sparkling 4K restoration on the big screen last month, I was struck all over again by its almost mythic power. The opening half hour, establishing its sprawling cast during Connie Corleone’s wedding, is an exhilarating stretch of film, and the famous baptism sequence is still beautiful, horrifying and electric. Gordon Willis’ moody cinematography lends the story a golden sepia glow and subsumes its characters in chasms of shadow. Brando’s Oscar-winning performance is perhaps the most parodied piece of acting ever, and yet his work hasn’t been cheapened by the imitators; he is sturdy and imposing and just a little weird, and he injects the character with unexpected notes of softness and humanity.

If there is a debate surrounding the greatness of “The Godfather,” it’s about whether it’s slightly better or slightly worse than its equally beloved 1974 sequel. I can’t choose a favorite, because both films come together to form an epic of unchecked ambition, of characters being pushed along by fates of their own making, and of the American dream falling prey to its own darkest impulses.