‘No More Stolen Sisters’: Indigenous artists curate Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women exhibit during Women’s History Month

In celebration of Women’s History Month, Gonzaga University’s Urban Arts Center is hosting the exhibition “No More Stolen Sisters” to raise awareness for the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women campaign primarily in the Pacific Northwest region.

Spokane Tribal member Jeff Ferguson, the curator of the event, also served as the master of ceremonies along with Margo Hill, a fellow member of the Spokane Tribe. “Murdered and missing Indigenous women is a serious matter, but today, we are not sad or mad,” Hill said. “We are here to honor the resiliency of our people. We honor Indigenous women.”

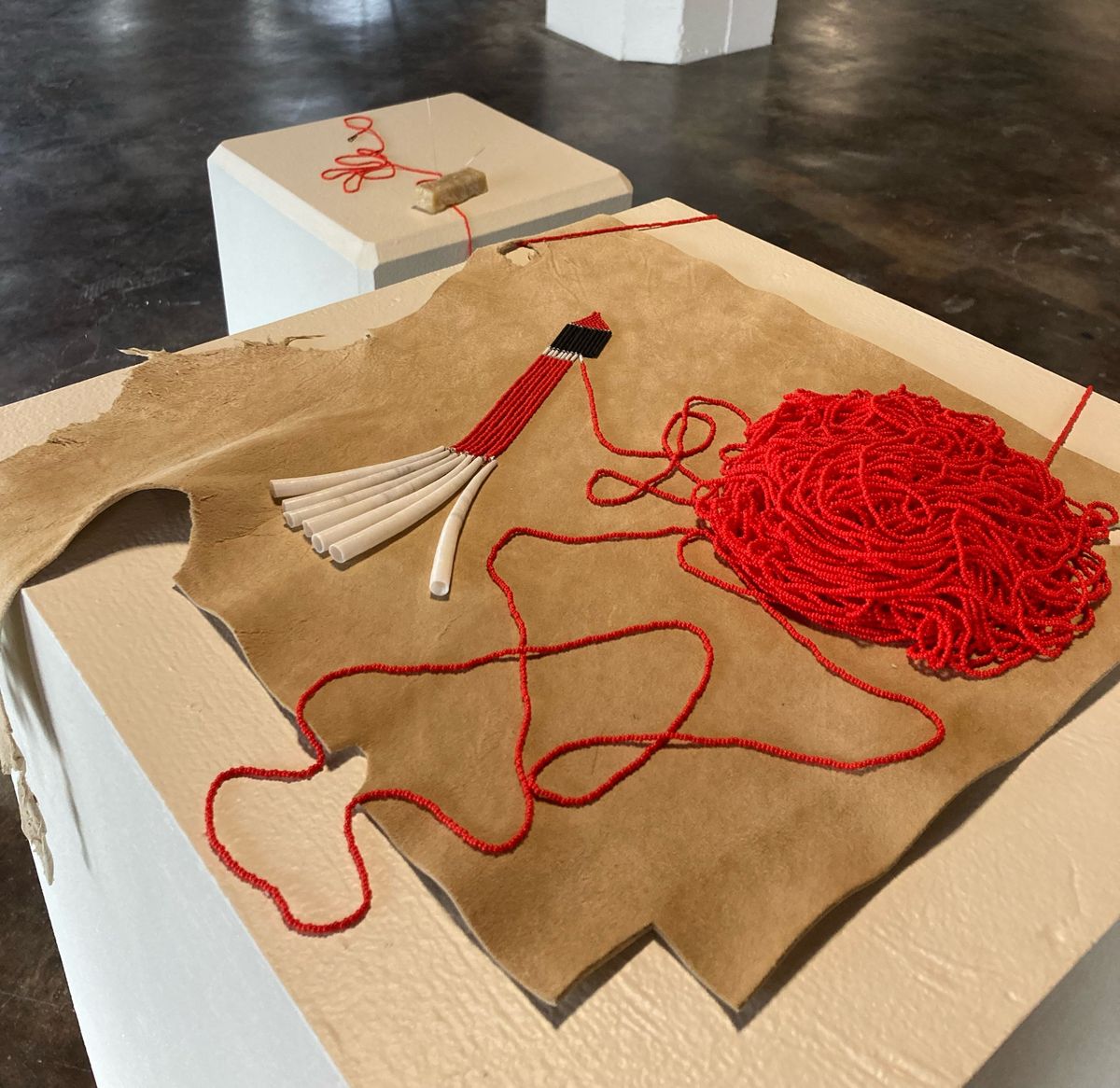

Instead of a traditional exhibition, “No More Stolen Sisters” was more of a direct call to action. “I thought this was a very creative way to get the message out,” said Patsy Whitefoot, a Yakama Nation elder who has been part of the MMIW fight for decades. “I don’t think I’ve been to one like this. It’s wonderful the kind of messaging you get. I love the paintings, the beadwork, everything. There’s a message that changes the mindset that’s here.”

Whitefoot has also mastered the art-activism binary: She’s dedicated her life in on-the-ground activism and is the founder of the Little Swans dance team. The group wears red outfits to commemorate murdered and missing Indigenous women at powwows and dance competitions. Whitefoot’s sister has been missing for almost 30 years.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, homicide is the third leading cause of death for Indigenous women ages 10-24 and the fifth leading cause for women 25 to 34. In Spokane County, there are currently a dozen cases open for missing Indigenous women.

At the entrance to the exhibit stood three large prints of 100 missing Indigenous women. Cases were as dated as George W. McDonald, who, according to the Colville Tribal Police Department, went missing on July 13, 1982. The most current case is Alberta F. Stahi, reported missing on Jan. 30.

Emily Migliazzo quietly sobbed at the list. She is a teacher at the Salish Spokane School and recognized the name of a former student they’d found in February.

“She was a really sweet girl who had to deal with a lot,” Migiliazzo said. “For her going-away party at the end of the school year, we barbecued her some salmon because that’s what she wanted. Really, really difficult life, but just so sweet most of the time.”

Migiliazzo, a white woman, visited the exhibition as a chance to connect with the students she teaches outside the classroom. She called “No More Stolen Sisters” an event to understand “the amount of loss that they’ll experience over their lifetime.”

“They just deal with so much mental health things, and most of my kids are in counseling right now. There’s awareness of the things that are going on in their community and the dangers of what it means to be an Indigenous woman or child,” Migiliazzo said.

In the middle of the main exhibition room, Idella King told the story of how her sister was killed on June 19, 2004. King described the systemic, cultural negligence that harms Indigenous women. She was killed by her partner in Montana.

“June 19 was Father’s Day that year. That was how my father celebrated that day: my sister dying, being killed on that day. It was unreal,” she said.

Still, in their collective trauma of vanishing women and girls, King reflected on her memories of preparing her sister’s physical body for her homegoing.

“We had a double tepee in the back of the yard, and that’s where she came home to,” King said. “That was the last time I braided my sister’s hair.”

She closed with a call to action to return and connect with Indigenous healing practices.

“Find out about your tribal ways,” King said. “Because that healing is the only way that I can stand up here and talk about what I experienced. This war bonnet that I wear, this rattle that I have, are all part of my healing.”

Indigenous artists like Arrow Lakes Band member Ric Gendron, whose work uses vibrant and poignant hues to capture Indigenous life, were featured in the exhibition. Regalia pieces, dolls and war bonnets displayed the richness of Indigenous women’s traditions.

Ione Yellowjohn, a descendent of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe, presented an embroidered, beaded jacket with two bald eagles resting on the shoulders. Yellowjohn considers the animal “strong, beautiful and powerful.” The beads start in purple and transition into white fog.

“It reminds me of the mist early in the morning,” Yellowjohn explained in her artist statement. “I look at the trees so peaceful and calm. I love beading animals in motion.”

One section of the exhibit features artists who captured the male perspective of losing mothers, sisters and other female community members who are the backbone of their community.

Lee Sekaquaptewa, an artist with Yakama, Navajo and Hope Tribe heritage, crafted a black-and-white face of his friend Carmen, an Indigenous woman, on a wood panel. Red papier-mâché doll cutouts spiral over but never meet Carmen’s face.

Sekaquaptewa also made note that the triangle that’s formed when the dolls hold hands represents “the trial and journey of what Indigenous women are going through.”

The papier-mâché dolls not only add dimension, but also the moving downward spiral of the holes in Indigenous communities once women are taken.

“When our women are taken away, disappearing, they’re the ones who hold the stories and families together. That’s what’s disappearing with them.” Sekaquaptewa said.

Hill, a former attorney, also participated in the testimonies, showcasing a data report that highlights human trafficking in Indigenous communities. During the presentation, she presented a map that shows missing Indigenous women throughout the state of Washington. Four cases are open in Spokane County.

During the exhibition, Ferguson also introduced a system similar to Amber Alert that immediately notifies surrounding areas about a missing Indigenous woman. Investigators note reporting a missing person 72 hours after they go missing increases her likelihood to be found.

“Everything that we do, whether it’s an art show or passing a bill, we’re outnumbered 98 to 2,” Ferguson said. “We can’t do this alone. We need our non-Native allies to help us snowball these efforts, these movements. It can be done.”