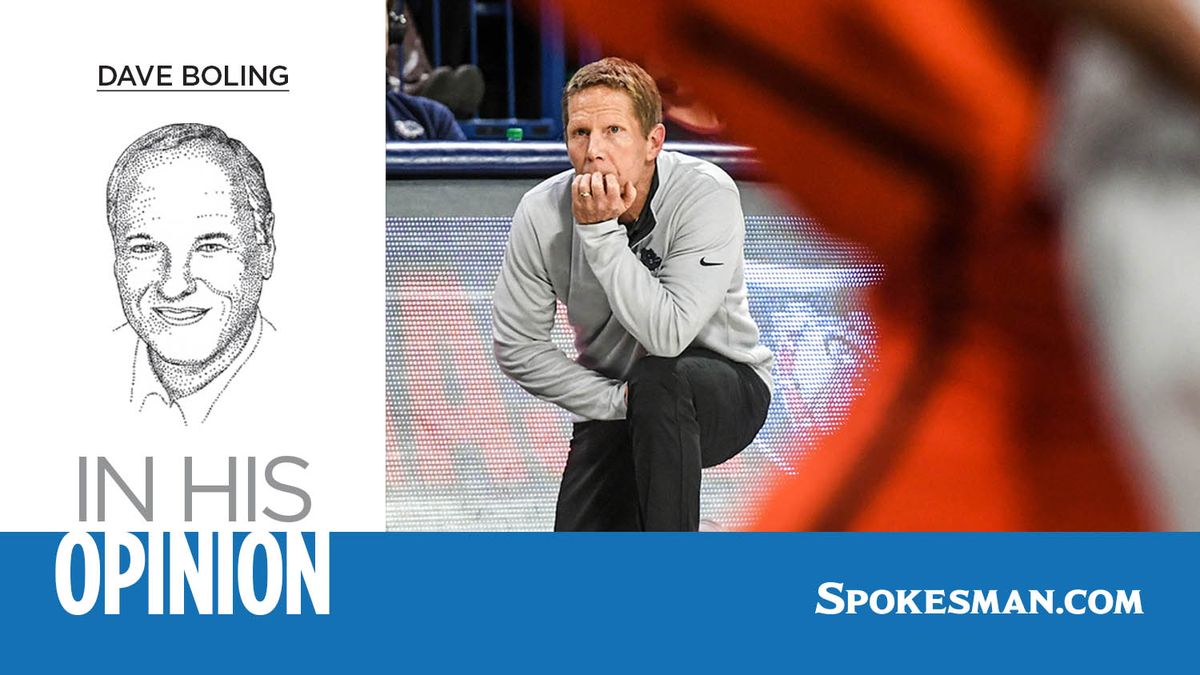

Dave Boling: Always-adapting Mark Few isn’t college basketball’s winningest coach by accident

Mark Few doesn’t have much practice explaining defeats.

After two of the three losses the Gonzaga men’s basketball team suffered this season, Few credited the opponents for being more aggressive and purposeful.

The “aggressive” part seemed obvious as both Alabama and Saint Mary’s were highly motivated by the chance to knock off the favored Zags. But the “purposeful” adjective sounded vague and somewhat New-Agey.

Few benefits from a more-than-adequate vocabulary, so it wasn’t simple redundancy; he clearly was citing an element crucial to his team’s success.

By all accounts of his early years, Few was hypercompetitive and intense. He never seemed like one who, during a timeout, would instruct his players to front the post, switch on the pick and roll, and, oh, yeah, follow your bliss.

Those were the days when coaches often were firebreathers, reacting to player mistakes with punitive drills and profane derision.

But no coach builds the best winning percentage in the history of college basketball, as Few has, by clinging to outdated methods. Holistic and relationship-based coaching worked fine for Phil Jackson and Pete Carroll, and others who recognized that coaching has become a matter of effective messaging.

“I think it’s always been one of (Few’s) strengths, changing and adapting, and never being satisfied with what happened the previous year, always making adjustments,” said Mike Nilson, a former Zags player on the GU strength and conditioning staff, working primarily with the women’s basketball team. “I think that’s why they’ve continued to thrive through the years and are always improving.”

Nilson supplies sound perspective on Few’s growth and changes. One, he was the epitome of old-school Zagliness, arriving as a walk-on while Few was still an assistant in 1997, and leaving in 2000 as the WCC Defensive Player of the Year. He was on the floor during the genesis moments of GU’s national emergence, and has been in the building and close to the team as it sustained national prominence.

“Coach Few and his staff have invested a lot of resources into personal development, the mental performance, growing leadership – the things we know are important, but a lot of coaches might not address. It’s easy to work on a two-foot jumpstop, but working on grit and growth mindset and gratitude are things that are at the heart of what we do here.”

The Zags focus on those qualities during a weekly period called Personal Growth Mondays. PGMs.

“This is something coach Few, Travis Knight (men’s strength and conditioning coach) and the staff have been doing, and just gave a name to it in the past four or five years,” Nilson said. “It’s working on the mental side of things, and the emotional side of sport, to see how that can help build stronger teams and more resilient players.”

PGMs, generally, occupy a 15-minute or so period with no coaches involved.

“We explore personal growth for the benefit of themselves and their game, mindfulness, visualization, how they can use their strengths to contribute to the team,” Nilson said. “It’s a new presentation every week.”

Nilson said the program has received positive responses from the players, and seems to have impressed some of the team’s recruits.

“Coach Few and the staff spend a lot of time with the families of recruits, showing them what we’re about. When recruits leave here they’re either saying, yes, they want to be a part of something like this, the family atmosphere, or maybe they leave because they want to be the star and maybe have some different priorities.”

That’s why, Nilson suggests, platinum prospects like Jalen Suggs and Chet Holmgren have fit in so well and quickly, being willing to focus on their roles and on winning games rather than just showcasing themselves for NBA scouts.

Can the effects of the positive-growth message be seen on the court? The win totals and rankings should stand as validation. Even if the message doesn’t always fit an individual, the effort to deliver the message carries meaning in itself. Studies of motivation show that employees in a work setting most care about being cared about, and knowing that somebody is trying to improve their experience.

“People on the outside might think (Few) has mellowed, but he’s constantly working,” Nilson said. “Having assistants like Tommy Lloyd (now head coach at Arizona) and Brian Michaelson – really intense coaches in practices – allows him to step back and see things from a different angle.”

Of course a person evolves during an improbable evolution from an inexperienced graduate assistant coach at a middling program to a sure Hall of Fame career as head coach of an annual powerhouse. Plus, Few is less than a year away from turning 60.

“I think having his kids growing and going through their basketball experiences has given him a lot of empathy,” Nilson said. “I think he has a deeper understanding, being a parent and living through the eyes of his kids, and that helps him connect with his players even more.”

Amid this praise for coaching adaptations, it’s probably fair to point out that Few had his own personal-growth experience last fall, pleading guilty to a DUI. For the first time in more than 30 years at Gonzaga, he wobbled on the pedestal built of competitive success and universal respect. In response, he expressed convincing remorse. “Please know that I am committed to learning from this mistake and will work to earn back your trust in me.”

Clearly, embracing a growth mindset and attaining self-knowledge is valuable at the top of the program, too.

Coaches have grown to understand that you don’t build a team by tearing down its individuals. And they’re recognizing that fully actualized people make better players, ones who also stand a good chance of coming out of the experience a better person in the bargain, which should be the purpose of sports in the first place.