Almira students to adjust to portables as construction about to start on new school, replacing one destroyed by fire

Almira School eighth-graders play some hoops Wednesday on a backboard salvaged from the playground after a fire destroyed their K-8 school building last fall. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVI)

It has been a volatile year for the students, staff and parents of Almira School. Since their school burned down last fall, they have had to adapt to multiple temporary learning environments and mourn the loss of their beloved building that housed memorabilia dating back to the 1800s.

“It was kind of like a museum for this town,” sixth-grade student Coy Wallace said.

About 140 students attend school in Almira from kindergarten through eighth grade before they attend Almira Coulee Hartline High School in Coulee City 20 miles away.

Groundwork for a new building is expected to begin this week on the site of the former school. The administration hopes it will be ready for students as soon as the fall of 2023.

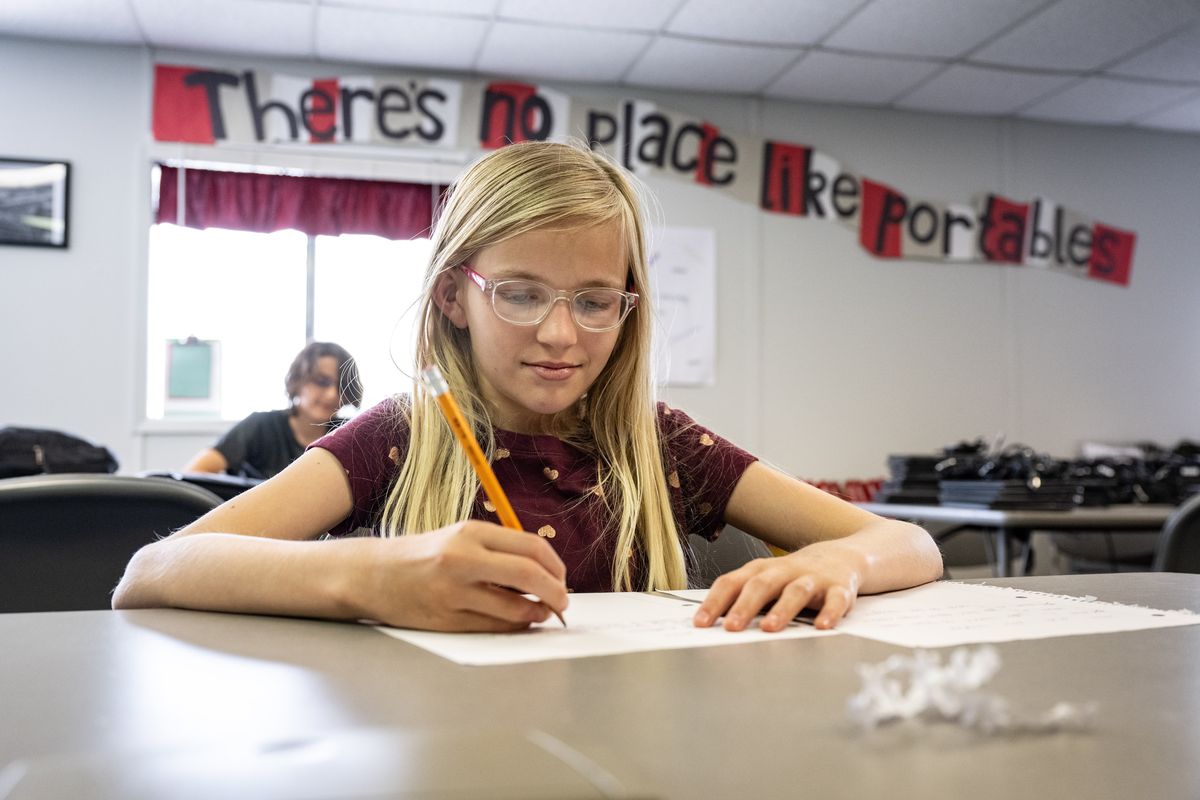

In the meantime, students are attending classes on a makeshift campus of portable classrooms on the school’s football field across the street.

“It was a little intimidating at first, with the unknown of it all,” Almira Principal Kelsey Hoppe said, “but the kids are super flexible and just adapted to it really well.”

Seven portable units, each containing two classrooms, form a neat quad with a courtyard in the center. One unit holds the office and library, another holds the cafeteria and band room and the rest are regular classrooms. The classrooms do not have running water, but two additional portables contain restrooms for the elementary and middle school students.

The temporary school even has a playground, with equipment that survived the fire and was relocated from across the street.

Except for the scoreboard in the corner, the former football field looks unrecognizable. “It will turn into a football field again one day,” Hoppe said. Until then, student athletes will practice and compete in Coulee City.

Figuring out the logistics of how to continue schooling would have been a challenge for any leader, and yet this was both Hoppe’s first year at the school and her first year as a principal.

“It was a whirlwind,” she said. “I don’t really have words to describe it, but it was a wild ride. It was amazing to see the support.”

The school caught fire in the late afternoon on Oct. 12. No one was inside because school had been canceled that day due to a power outage. Fire crews responded from as far as Ephrata and Grand Coulee.

The town gathered to watch, helplessly, from the football field as the building burned down. It continued to smolder overnight until there was essentially nothing left.

“It was really devastating,” sixth-grader Savannah Monson said. “I’ve gone to that school my whole life, I started in pre-K, and just to see it burn in front of me, I was really sad, and it took a while to get over.”

Investigations involving the fire department, the school’s insurance company, the utility company and other contractors that had worked on the school were unable to determine the cause fire, but did determine that it started in the pre-K room in the northwest corner of the school, said Dennis Pinar, fire chief at Lincoln County Fire District 8 Almira. He said that it did not appear to have been caused by the power outage.

The Almira School was built in 1952 after another fire damaged the previous school building in 1951.

After a fire destroyed their K-8 school building last fall, students and staff have spent the year in portable classrooms while the new Almira School building is constructed in the Lincoln County rural town. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVI)

Sean Matthewson, the middle school math teacher, said his biggest challenge is not having access to all the resources and materials amassed over the years that were destroyed – especially paper curriculum that was not backed up online.

“We all felt like we were a first-year teacher after the fire, just starting over,” he said. “Whether you are a second-year teacher or a 30-year teacher, we all have that same feeling.”

After the fire, elementary students attended classes at the Almira Community Center and Almira Community Church, while the middle school students were bused to the high school in Coulee City. The elementary and middle school moved into the portable classrooms in March.

Students said having to move around several times during the school year was difficult, disruptive and confusing, but they are glad to have their own space again.

“It has been really weird,” said sixth-grader Ayden Bresee, “but I know we’ve been trying to get back to normal, slowly. Learning has been great in the portables.”

“I feel like we have become more adaptive and learned how to deal with different situations,” Savannah Monson said.

Malory Isaak, who is also in sixth grade, said they have made the best of it, and the teachers have made the portables feel like home.

“It’s been challenging, but I feel like we have overcome the challenges.”

The students are eager to watch the construction of their new school over the next year. Sixth-graders, especially, hope it will be finished in time for them to attend eighth grade before they go to high school in Coulee City.

“That will be an educational experience as well, you know, letting the kids see that progress,” Matthewson said. He plans to work the blueprints into some of his math lessons.

The disaster was an unlikely chance to start over, for Almira to upgrade and redesign their own school based on current needs.

“Of course the fire was tragic, but the community and staff pretty quickly looked at it as a glass half-full opportunity to build a school,” said Gene Sementi, retired West Valley School District superintendent. The Almira School District hired him as a consultant and project manager to help with logistics since the fire.

“The old school lasted 70 years, which is pretty great. So the chance to build a new school that will last another 70 or 80 years came up out of the ashes. People are excited about it,” he said.

A committee has met almost weekly since December to work on the plans, Hoppe said. The community reviewed the plans and gave input at several open houses with architects early this year.

The new building will have a similar footprint to the original 35,000-square-foot school, but the academic wing will get a second story for the middle school classrooms, adding an extra 12,000 square feet. The plans also add a science lab, an art room, several breakout rooms and quiet study spaces.

The total budget of the project has not been finalized, but it will be funded by a combination of insurance settlement funds, almost $13 million from the state budget, grants from the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction and fundraising from the Columbia Basin Foundation.

Reflecting on the second-to-last day of the school year last week, Matthewson sensed that the school was ultimately able to make the situation work and that the kids are genuinely happy.

“They will look back on it and understand this is a really good, positive life lesson that they went through,” he said.