An Amazon uprising and the fight for a second warehouse

NEW YORK – As soon as Chris Smalls ended one call, his phone buzzed again. It had been that way for three days, ever since the 33-year-old and his team had won a vote to unionize an Amazon warehouse, a first in the company’s history.

“I don’t have an assistant. It’s just me,” he was telling a television producer whose name and show he would quickly forget. “Send me another text tomorrow, and I’ll call from wherever I’m at.”

The Amazon Labor Union’s win in early April – at the same 8,300-person facility on Staten Island where Smalls had been fired – defied almost every rule of organizing. With virtually no money, experience or help from big unions, Smalls and his team had convinced a building full of disaffected workers that they could fight for themselves and win.

Now Smalls, with his “Eat the Rich” sweatsuits, sunglasses and gold chains, was being touted as the leader of a new kind of worker-led uprising, one that could reinvigorate a shrinking labor movement. He also faced tough questions: Could the unruly, often-chaotic movement that he had helped to spark spread to other Amazon warehouses? A vote at a second Staten Island facility was scheduled for April 25, about three weeks away. Could he and his fellow warehouse workers ever amass enough power to wrest concessions from Amazon and actually improve their lives?

Around 9 p.m., Smalls was sitting in the front seat of a beat-up SUV that doubled as his office when his phone started ringing again, this time with news that a worker he knew had been suspended for fighting with some employees and needed his help. He FaceTimed the worker’s manager and, when she didn’t respond, fired off a text asking what had happened.

“Just fyi I officially represent the workers so they are going to tell me,” he wrote.

“So, go through the right channels,” the manager texted back.

“Lol you my friend or nah,” Smalls typed. “The right channels stfu lol.”

He climbed out of his car and headed into the living room of a small Staten Island duplex that served as the union’s temporary headquarters. Bags of trash and a dirty gray carpet covered the floor. Trays of molding ziti filled the refrigerator. The senior members of Smalls’s team sat on plastic folding chairs and discussed plans for the coming week: State lawmakers in Albany wanted to give Smalls an award. The head of the Teamsters union wanted to meet with him in D.C. The election at the second warehouse was fast approaching.

By 2 a.m., most of the staffers had drifted home. Only Smalls and Brett Daniels, a night-shift worker and the union’s director of organizing, remained. The two smoked a joint and Smalls dived into the thousands of unopened texts and emails on his phone.

Many were from Amazon workers who had been inspired by the Staten Island victory and wanted to unionize, too. Smalls skimmed a message from an Amazon driver in Kansas City, Mo. “I’ve never been to Kansas City,” he said. “That’d be a dope trip.”

He read an email from a worker in Sacramento, Calif., who was complaining about the abuse she was suffering on the job. “No one here gives a flying fudge about my wellbeing,” she wrote. The Staten Island win, she continued, had “sparked a fire” and a “hunger” in her.

“I’m calling her tomorrow. I ain’t playing,” Smalls said. “It’s lit, bro. It’s lit. We’re going to Cali.”

It wasn’t just Amazon workers. Walmart, Target and Dollar General employees wanted his help, too. There were so many requests pouring in through so many channels that Smalls and his team had for the moment given up on keeping track of them all. Smalls looked up from his phone and flashed a grin that revealed teeth covered in gold grillz.

“We just made unionizing cool as f—-,” he said.

Smalls’s breaking point with Amazon came in March 2020 at a moment when the pandemic was raging in New York City and so many workers around the country were reevaluating their relationships with their employers.

By then, he had been with Amazon for nearly five years, worked at three warehouses and been promoted to “process assistant,” a low-level management position. He had been briefly terminated – and then reinstated after a six-week battle – for stealing two minutes of the company’s time. “It was so ridiculous,” he said of the way he had been treated.

And so when he learned that a worker in his building had tested positive for the coronavirus, he suspected that Amazon didn’t have his or his co-workers’ best interests at heart.

For a week, Smalls said, he pressed the JFK8 warehouse’s top managers to shut down and clean the facility. When that failed, he led a walkout that got him fired and caught the attention of Amazon’s general counsel in Seattle, who wrote in an email leaked to Vice News that Smalls was “not smart or articulate.”

Smalls was reaching his own conclusions: “I’ll never work for anybody again,” he recalled thinking. He began searching online for the addresses of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s homes in New York City, D.C., Beverly Hills and Seattle, where he then organized demonstrations. (Bezos owns the Washington Post.) Sometimes a couple dozen people attended; sometimes a couple hundred. At each stop, Smalls raised his megaphone to a mostly empty, heavily guarded mansion and led the protesters in a call and response.

“F- – Jeff Bezos!” he yelled and the crowd repeated in kind.

One year into his crusade, Smalls realized that shouting at houses wasn’t going to produce lasting change, so he set up a tent on public property next to a bus stop across from the warehouse where he had been fired and began organizing a union. A far larger, better-funded effort by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union was already underway to organize an Amazon facility in Bessemer, Ala.

Smalls was starting with almost nothing. Via tweet, he found a lawyer willing to help for free.

The core of his initial team was warehouse workers whom he had supervised in New York or who had found him outside one of Bezos’s mansions. The rest ran into him at the bus stop, where Smalls strove to build a haven for workers who often complained that they were abused and surveilled. Amid a miasma of exhaust, Smalls lit a firepit on cold nights, played music, served food and made s’mores.

Angelika Maldonado, a 27-year-old single mom, was feeling sick when she cut short her 12-hour shift one night last October. She missed her bus, but there was Smalls. Someone from his team invited her over to the tent and asked her what she thought they could gain from unionizing.

Maldonado talked about her struggle to afford the $54 weekly health-care premium for her and her son. Smalls handed her a slice of pumpkin pie.

She spent six hours at the tent that first night, returning home with the sunrise about 5 a.m., and then quickly became a regular. She’d just broken up with her boyfriend and moved in with her mother. For her, the tent became an escape from the drudgery and isolation of working the overnight shift at Amazon.

Michelle Valentin Nieves, 45, was screaming at a manager in the JFK8 warehouse when one of Smalls’s best friends approached her about the union. On her phone was a year-old picture of her and a dozen co-workers – from Panama, Colombia, Peru, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. “Los Originales,” read the caption. They’d gone to birthday parties, baby showers, and bowling and karaoke nights together.

Now only three, including Nieves, were left. They were people with “families, mortgages and car notes,” Nieves said. The pandemic had left people stranded at home and caused Amazon’s business to boom. The surge in demand put new pressures on Amazon workers in places like Staten Island. Some of Nieves’s friends had grown tired of a workplace where their every move, including bathroom breaks, was tracked by sensors and scrutinized by managers. Others were fired for arguing with bosses or failing to meet production targets, a common occurrence at Amazon warehouses, which typically have 100 percent turnover annually.

Amazon officials said the surveillance is needed to keep employees and inventory safe. The churn is a function of the company’s flexible work environment, they said. “A large percentage of people we hire are re-hires, showing that they will choose to work with us when they want to, then come back when it’s convenient for them – and we’re glad they’re on our team,” said Kelly Nantel, an Amazon spokeswoman.

Nieves attributed the high attrition to the grinding nature of the labor. “There’s no culture here,” she said. “You just produce, produce, produce.”

In Smalls, she saw someone like her – someone who was “tired of the B.S.”

The workers were joined by a half-dozen outsiders – most of them recent college graduates – who had seen Smalls on the news and signed up to help him fight Amazon, a company that posted soaring profits throughout the pandemic and to them epitomized everything that was cruel and unjust in the U.S. economy. Smalls couldn’t pay them, so they got warehouse jobs and worked with him to organize Amazon from the inside.

To trigger an election, Smalls and his team needed to persuade at least 30% of the workers at an Amazon building to sign authorization cards. By early 2022, the union had collected enough signatures for votes at two Staten Island warehouses – known as JFK8 and LDJ5. The JFK8 warehouse was set to go first.

About the same time, the union scored a big legal win. Amazon reached a settlement with the National Labor Relations Board that allowed employees to stay and organize in their building’s nonwork areas even when they were off the clock. Smalls held down the tent by the bus stop. His worker-organizers occupied the break rooms, passing out pro-union literature and serving hot meals.

When the votes were counted on April 1, showing that the union had won by more than 500 votes, international media descended on Staten Island, and Smalls became an overnight star. President Biden gave him a shout-out: “Amazon, here we come.”

“What an insane story,” raved “Daily Show” host Trevor Noah with Smalls sitting next to him in the studio.

Smalls was often asked how he had done it. Sometimes he focused on his team’s firsthand knowledge of the workers’ struggles. “We live the grievances, the reality of the warehouse,” he said. Sometimes he talked about the culture they’d built at the bus stop: the food, the music, the friendships.

“The one thing that Amazon can’t buy is love,” he said.

The truth, he’d realized as he prepared for the next warehouse’s vote, was that he’d been willing to spend 11 months at a dirty bus stop, fighting to prove himself to the workers.

“It was day after day working straight,” he said. “We were there with the bonfires. We were there with rallies. We were there at every shift change. There’s no secrecy. You have to go all in.”

The lead organizer for the next vote was Maddie Wesley, 23, whose pathway to Amazon was in so many ways the opposite of Smalls’s. She had graduated from Wesleyan University in Connecticut in 2020 and was living in Florida last summer when Seth Goldstein, the labor lawyer who had responded to Smalls’ tweet asking for help, called her. The two had worked together organizing campus custodial workers when Wesley was a student.

Wesley had tentatively signed on to work with Unite Here, a big union with 300,000 members that was organizing hotel workers in South Florida. Goldstein urged her to drop the job. “This is the kind of stuff you and I dream about,” he told her of Smalls’ effort. “This is a chance to make history.”

In August, she moved north and got a job at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island. Wesley knew that the poorly funded, worker-led campaign was a long shot. Smalls didn’t even have money to pay her. But she also understood that the payoff, if it succeeded, could be huge.

Amazon workers held a critical position at the heart of the U.S. economy. Smalls was building an organization that could help them exercise their power. To Wesley, the effort seemed potentially “revolutionary.”

Her first sense of Smalls’s potential as a leader came days after her move at a Medicare-for-all rally in Manhattan. Smalls was late and the rally, organized by another group, was a mess. Activists were fighting over the megaphones. Their chants were way too complicated. “Chris finally shows up and all the issues just melt away,” she recalled. “He’s able to take over and lead the whole protest. I saw his potential to really lead a movement.”

When the final tally came in showing the union’s win at the first warehouse, Wesley stood cheering next to Smalls as he popped champagne on a Brooklyn sidewalk. But as the days passed, she worried that the spotlight was introducing new strains on the group and on Smalls, who she said was struggling to balance running a union and being the face of a movement. She missed the simplicity of their “dirty-little-tent days,” when they were all equals.

Now, Wesley was once again waiting on Smalls, who was late. The victorious worker-organizers from the first warehouse were meeting with Wesley and the team she had recruited for the second vote. The union didn’t have office space, so a Staten Island chapter of the Communications Workers of America lent them a room.

“Is Chris pulling up?” one of the organizers asked.

“Theoretically,” Wesley replied.

The group got started without him. All eyes turned to Wesley, who stood beside a whiteboard at the front of the room. The union depended on donations collected via a GoFundMe account that since the win had ballooned from virtually nothing to more than $120,000. “The good news is that we’re rolling in dough,” said Wesley, who doubled as the union’s treasurer.

The bad news was that they were up against a $1 trillion company, which had been surprised by the loss at the JFK8 warehouse and was already ramping up spending to counter the union’s message at the second facility.

Wesley sketched out a round-the-clock plan to occupy the LDJ5 warehouse break rooms, where she and her team would serve food and pass out leaflets outlining the union’s demands: better wages, more job security, a pension fund, better health benefits.

The JFK8 workers talked about the tactics they had used to win over union skeptics.

Eventually, Smalls arrived and assured them that he was going to set up the tent by the bus stop, just as he had during the earlier campaign. Because he was no longer an Amazon worker, Smalls wasn’t allowed on company property. In February, he had been in a warehouse parking lot delivering food to workers when Amazon called the police and he was arrested.

“I’m going to catch all your stragglers … day and night,” he told Wesley at the meeting. “I got you. I’ll be there.”

When the meeting ended, Smalls lingered by the front door. His movement suddenly had money and momentum. But Smalls sensed that something was wrong. For the past several months, the union’s all-consuming focus had been winning the election at JFK8, which was five times the size of the 1,600-worker LDJ5 facility.

Smalls worried that Wesley and her team – many of whom had been focused on helping with the first warehouse campaign – didn’t have a good handle on the problems and frustrations of workers inside their building. With only 20 days until the voting started, he knew that they were running out of time. “It’s like starting over,” Smalls told an organizer from the JFK8 warehouse. “We gotta go hard. It’s gotta be a full-on assault.”

He climbed into his SUV and was gone.

Days passed, and the demands on Smalls’s time exploded in ways he never imagined.

In Manhattan, the New York City comptroller wanted to discuss ways that he and other big pension fund investors could put pressure on Amazon to lower its worker injury rate. The next day Smalls traveled to D.C., where he met with members of Congress and labor leaders who were offering money and expertise.

He and his team visited Albany, N.Y., where they were the guests of honor at a luncheon hosted by a coalition of minority lawmakers and sponsored, in part, by Amazon. “It just goes to show how they try to control everything,” Smalls said.

The NAACP invited him to Detroit. Another group was offering to fly him to Cuba. He appeared alongside actress Susan Sarandon at a rally in Manhattan. He was a near-daily presence on cable news.

Much of it was important work. But it was far from the daily concerns of the warehouse workers on Staten Island. About a week into the campaign for the second warehouse, Smalls stopped by the bus shelter to pass out yellow union lanyards during a shift change. Empty cigarette packs, discarded work gloves and a folded-up Amazon ID littered the ground next to a makeshift memorial for a 24-year-old employee who had been fatally struck by a car on her way to work. The smell of diesel fumes, cigarettes and marijuana filled the air.

Smalls was on the phone with his lawyer, who was updating him on Amazon’s latest legal filing challenging the first vote. Amazon alleges that the National Labor Relations Board improperly “created the impression” it was supporting the union before the balloting and that Smalls and his team harassed employees to win their backing.

“Nobody cheated,” Smalls told his lawyer. “A trillion-dollar company loses and they want to cry.”

A former network news president was calling to gauge Smalls’s interest in a documentary film project. “Thank you. Thank you,” Smalls was telling him. “We’re still trying to get to the next level. It’s been a journey.”

An older woman with a limp who knew Smalls from the JFK8 warehouse rushed up to talk. He pointed at his headphones to signal that he was on a call and gave her a hug.

She returned to the conversation she was having with her co-worker about a manager who had criticized her hourly “rate” – the pace at which she worked – in front of others.

“He shouldn’t have said that!” she fumed.

“We need a change,” her friend agreed.

After about 15 minutes, the workers climbed onto the S-90 bus headed to the St. George Ferry Terminal and were gone. So was Smalls.

At the LDJ5 warehouse, Wesley was growing increasingly worried that she and her team of organizers were overmatched. Amazon, chastened by its earlier loss, moved virtually all of the anti-union consultants – some of whom charged as much as $3,200 a day, according to federal disclosure forms – into the smaller LDJ5 building.

“The [Amazon Labor Union] is trying to insult your intelligence,” read one of their anti-union fliers. “Its officers can put you on trial and fine and expel you.” Others reviewed by The Washington Post falsely accused the union of being a for-profit business and featured cartoon drawings of union officials surrounded by stacks of money and driving a convertible sports car. Amazon declined to comment on the activities of its anti-union consultants. “It’s our employees’ choice whether or not to join a union, it always has been,” the company said in a statement.

Most of the organizers that Wesley recruited were friends in their early 20s that she had made in the warehouse break room during her eight months with the company. They were all learning on the fly how to connect with demoralized co-workers who were often twice their age.

About a week into the campaign, Wesley began to worry. “We need you here,” Wesley warned Smalls in a phone call. “We’re going to lose this building.”

Wesley treasured the responsibility that Smalls and the union had given her. “This organization, it means so much to me,” she said.

Lately, though, the pressure was almost too much to bear. She had been sleeping only four hours a night and suffering panic attacks in which her heart would start racing as she was lying in bed. If the movement couldn’t spread to other warehouses, she knew it stood little chance against Amazon. “All this responsibility, this early in life,” she said, “it’s a lot.”

She wanted Smalls to press the JFK8 worker-organizers, who weren’t allowed inside the LDJ5 warehouse, to spend more time working the phone banks and passing out literature on the steps of the building. And she wanted Smalls to put in more time at the bus stop, where he could talk to workers, tell his story and counter the lies Amazon was spreading about him.

Smalls, who was also tired and stretched thin, told Wesley that he had more-pressing responsibilities. The union needed to find office space, lawyers and accountants. The outreach to Smalls from politicians and the international media hadn’t let up. “Being at the bus stop is not valuable to my time and not valuable to the organizing,” he told her.

About 10 days before voting was set to start, Wesley sat on the sidewalk by the LDJ5 warehouse’s front doors. The long hours inside the windowless building made the brightness of the afternoon sun overwhelming. Next to her was Julian Mitchell-Israel, who had landed a job at the warehouse in the fall after reading an article about the union drive in Jacobin, a socialist magazine. Mitchell-Israel, a graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio, had called Smalls to ask how he could help.

Both Wesley and Mitchell-Israel, 22, had backed the second presidential run of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), believing he might be able to galvanize a working-class movement like the one they were now trying to build at Amazon. In 2020, Sanders’s campaign slogan had been: “Fight for someone you don’t know.” The motto, they decided, explained why Sanders had failed to mobilize people like the workers in their warehouse.

“It should be fight for someone you love,” Mitchell-Israel argued.

“It should be fight for yourself,” Wesley insisted.

Their toughest job was persuading dispirited Amazon workers to fight at all. Many who opposed the union argued that the demands they were making – a $30-an-hour wage, pensions, free college for family members – were unrealistic. “You think you’re going to get $30 an hour for this?” one woman yelled at them. “This is not a career. You’re working at a warehouse.” Others insisted that many of their colleagues at the plant were undeserving or lazy. Or they said that they had decided to wait and see if the unionized workers at the JFK8 building across the street would be able to negotiate a better deal – a process that was likely to take at least a year.

Smalls’s chief of staff stopped by to check on Wesley and talk about their strategy for the final days of the campaign. Amazon was halting production for five hours each day so that employees could attend sessions with the warehouse’s general manager and a senior executive from Seattle. Wesley told him that anti-union workers were spreading false rumors that Smalls had bought her a Mercedes.

“You have a target on your back,” he said.

“I am second only to Chris Smalls,” Wesley replied.

Wesley believed that to win, she and her team had to shift the focus away from both her and Smalls, whom Amazon was portraying as an embittered employee with a vendetta against the company that had fired him.

“It’s not about me,” she said. “It’s not about Chris.”

She grabbed several boxes of pizza that had just arrived and headed back inside with them.

The workers would soon be arriving in the break room, and she needed to be there.

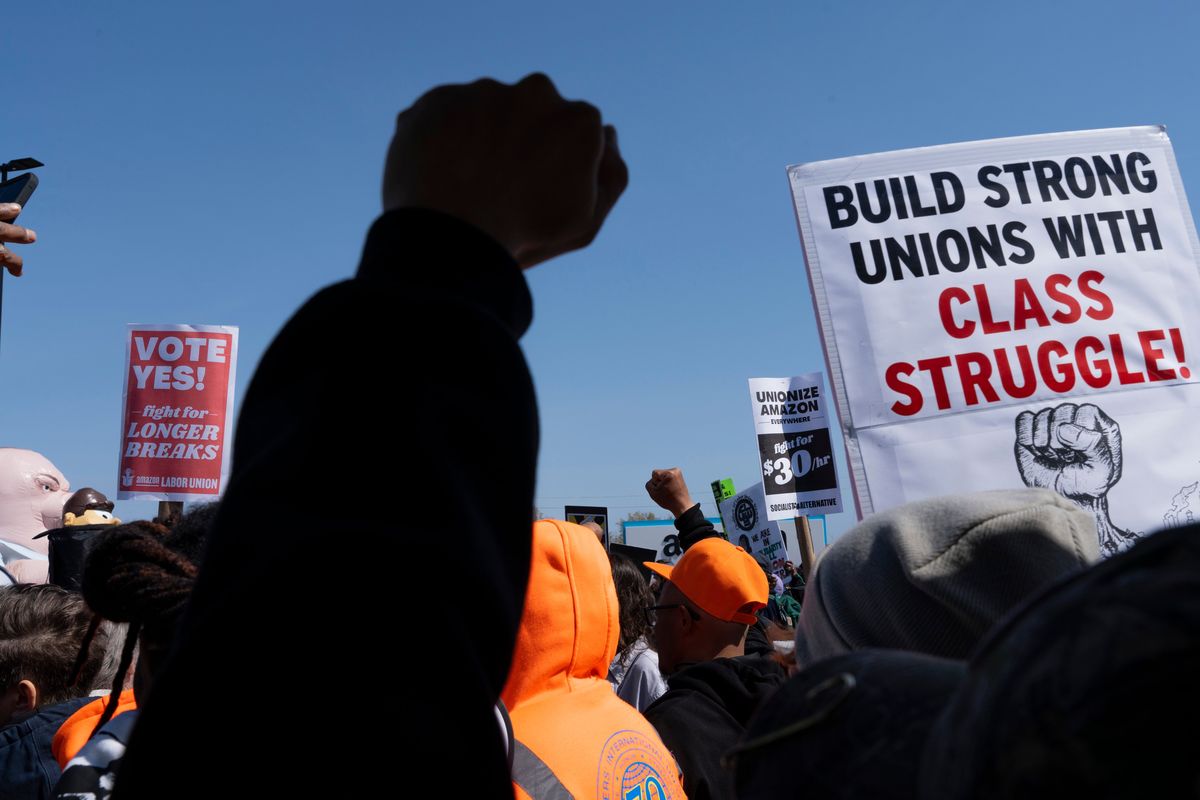

The day before the voting at LDJ5, Smalls and the rest of the Amazon Labor Union held a news conference and rally on a patch of grass halfway between the bus stop and the warehouse. The initial win and Smalls’ rising profile helped attract some heavy hitters who hadn’t been willing to make the trek to Staten Island for the first campaign.

“What you’re doing here is sending a message to every worker in America that the time is now to stand up to our oligarchy,” said Sanders, who had come from Washington.

Next up was Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat representing New York. “Let’s just give a big shout-out to the workers who did the damn thing!” she shouted in praise of Smalls and his team.

Eventually, Wesley climbed the riser and addressed the crowd. “This is our one chance to improve our livelihoods, to be a part of something truly great,” she said.

The voting was spread over four days. On May 2, Wesley, her black work boots untied, arrived at the National Labor Relations Board headquarters in Brooklyn to watch the final count. Smalls was en route from Detroit, where a day earlier, the NAACP had presented him with its Great Expectation Award.

The tally was done in about 90 minutes and ended in a rout. Of the roughly 1,600 workers eligible to vote, 380 voted in favor of unionizing and 618 voted no.

In the union’s win at the JFK8 warehouse, Smalls’s personal story – his COVID-19 protest, his firing, his two-year battle with the company – had been a critical part of the campaign’s closing argument. Workers who had toiled alongside Smalls before his firing or had spoken with him at the bus stop saw someone just like them. Most of the other JFK8 organizers, who became regulars at the Smalls’s tent, had worked at the warehouse for years.

At LDJ5, workers didn’t have the same bond with Smalls. To them, Smalls was “the guy with the gold chains” they had seen on the news or on Instagram. Some who voted no complained that the union was making unrealistic promises or said they didn’t want to pay dues. A few noted that the work in their warehouse wasn’t as hard as in the larger JFK8 facility.

Most of these workers knew Wesley and liked her. But they also knew she had come to Amazon to help organize it, not because she desperately needed a job. And while Wesley had recruited several workers to her organizing team, most had been reluctant to assume central roles that would turn them into targets or put their jobs in jeopardy. Others had families or stresses at home that prevented them from devoting weeks to a union campaign. So, much of the burden for the campaign fell on Wesley.

Once the votes were counted, Wesley who had been steeling herself for a loss, slipped away unnoticed.

Outside, members of the union’s organizing committee – many of whom had been key to the first win – were fending off questions from reporters.

“It’s just a bump in the road,” one said.

“A minor setback,” insisted another.

Everyone was waiting for Smalls, who projected confidence and calm when he arrived an hour later.

“What’s the strategy for the next vote?” one journalist asked.

“What about the 100 other warehouses that contacted you?” another pressed.

Smalls talked about his plans for a national video call this summer for Amazon workers around the country who were interested in organizing. And he emphasized the need for government reforms that would “level the playing field” and make it harder for companies such as Amazon to “crush workers’ voices” and “intimidate” those seeking to unionize. “We’re going to apply pressure to the ones that can make decisions and help us,” he told the reporters.

In the coming days, Smalls was scheduled to visit Washington, where, clad in his “Eat the Rich” jacket, he would testify before Congress and meet with the president in the White House.

“You got it done in one place,” Biden told him. “Let’s not stop.”

“That’s right,” Smalls replied.

Amazon officials touted the LDJ5 victory as proof that workers are satisfied with the company. “It’s our employees’ choice whether or not to join a union, it always has been,” said the Amazon spokesperson. “And in the case of LDJ5, our employees overwhelmingly rejected the union.”

Smalls, Wesley and the rest of the team knew that to put pressure on Amazon and win a contract – a process that could take years – the union would have to expand to other warehouses. And they knew that the people they needed didn’t live in Washington. They didn’t watch cable news or attend rallies. They were people with busy lives and bills that they were struggling to pay. They were the kind of people who were exhausted after a long shift and waiting at the Staten Island bus stop.

Smalls and his team were tired, too. He had spent the first year after his dismissal leading protests against Amazon and much of the second organizing and breathing exhaust fumes at the bus stop.

Someone urged him to help find Wesley.

“I’ve called her twice,” he said sharply. “She hasn’t picked up.”

Smalls was standing just steps from the spot where, a month earlier, he had popped a celebratory bottle of champagne. The reporters were gone. A light rain fell as he considered his next move.

- – -

Anna Betts contributed to this report.