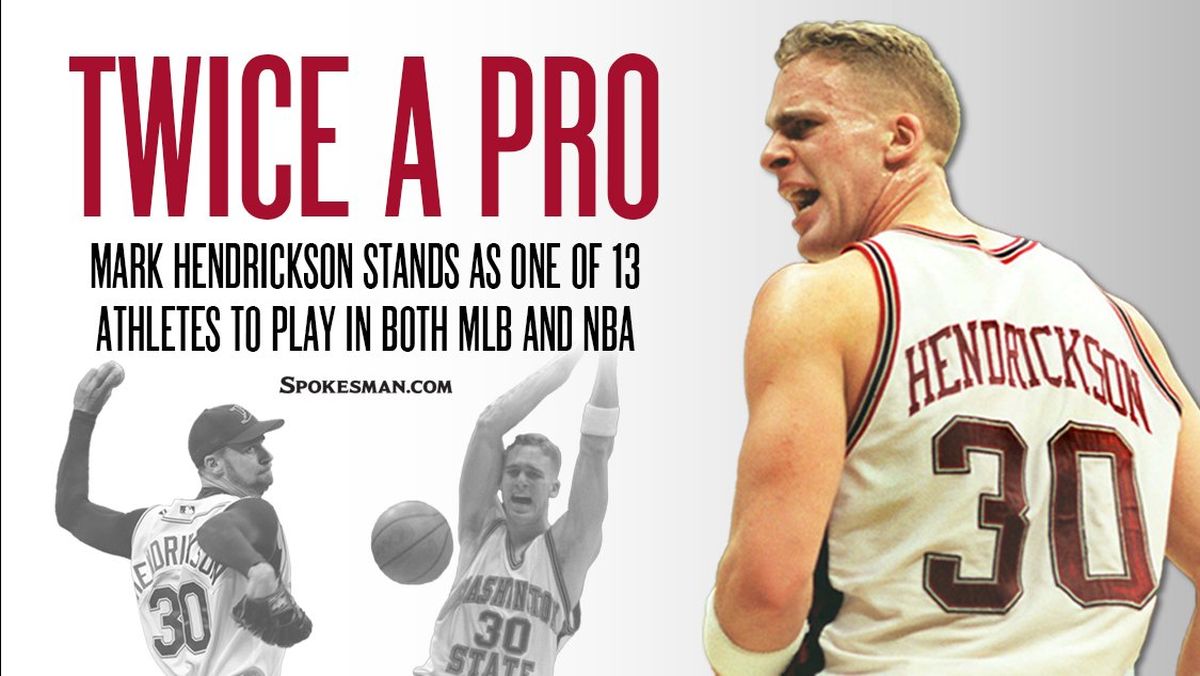

Twice a pro: Washington State’s Mark Hendrickson stands as one of 13 to play professionally in the MLB and NBA

There are 92 locales mentioned in the song “I’ve Been Everywhere,” made famous decades ago by the late Johnny Cash.

It would take Mark Hendrickson a stanza or two to recite the long list of places he’s lived and visited from spending 231/2 years of playing basketball and baseball both at the collegiate and professional levels.

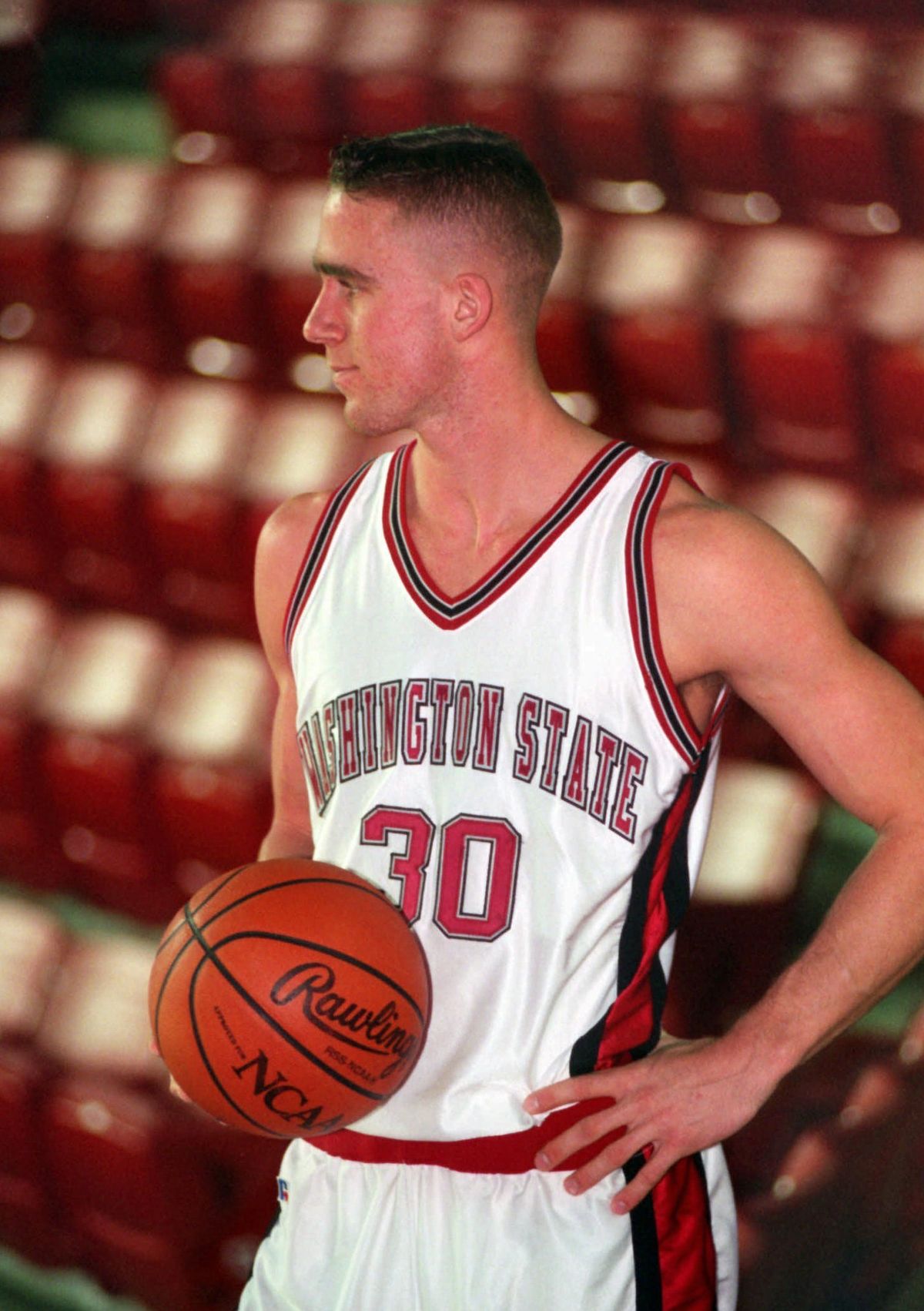

He first chased the vision while attending Washington State University from 1992-96, and then lived the dream as a forward in the National Basketball Association and as a pitcher in Major League Baseball.

“You learn to travel light, that’s for sure,” he said, seven years after ending that vagabond chapter of his life. “I lived out of suitcases, but it is what it is. You have to get used to that lifestyle.”

For the 6-foot-9 left-hander, the grind included preseason training camps and an 82-game season in basketball. For baseball, it started with spring training in Arizona or Florida for six to eight weeks, then living in a minor league town or a big league city for a 162-game schedule.

“It was life in a hotel,” he said in June from York, Pennsylvania, where he now shares a home with his wife, four daughters and two grandchildren. “It becomes a very nomadic life, even in college. I missed all the holidays and we spent them at the coach’s house. That wasn’t the same.”

This summer marks the 20-year anniversary of his major league debut – Aug. 6, 2002, while playing for the Toronto Blue Jays. Born and raised in Mount Vernon, Washington, Hendrickson’s debut came in a relief appearance versus the Seattle Mariners – his favorite team growing up.

Hendrickson entered in the eighth inning after a dominant outing from Hall of Famer Roy Halladay. He struck out the first batter, Carlos Guillen, on four pitches, but came down to earth allowing five runs on three hits and two walks before he was pulled.

It came at the Toronto Skydome, where he says the bullpen is under the enclosed portion of the stadium, but the pitcher’s mound left him in the open with a swirling wind in his face.

“It was the weirdest thing, and on top of that I was making my debut,” he recalled. “My heart is pounding and it just happened so quick. I don’t know if I was even close on any of my pitches, it just worked out that I got the strikeout. Then it was boom, boom, boom, boom. And of all teams to be playing it was Seattle, so a lot of people were watching.”

It certainly provided a noteworthy footnote to what would be a stellar career in the league.

“Obviously it didn’t start out very well,” laughs Hendrickson, who turned 47 in June. “Debuts are funny – you remember them but they sometimes don’t go the way you want.”

That was the beginning of a 10-year career in the majors, after completing a four-year tenure in the NBA. In all, he was in professional baseball from 1998 to 2015, including three years in the minor leagues testing his mettle as a two-sport player.

Hendrickson is just one of 13 players in history listed by the Baseball Almanac to play in both the NBA and MLB. Included are Danny Ainge, Dave DeBusschere and Gene Conley. Michael Jordan, mind you, was a superstar in the NBA but never made it to baseball’s highest level.

If he had to do it all over again, would Hendrickson pursue both sports at the professional level again? Without hesitation, Hendrickson answered in the affirmative, but with a warning label.

“You have to have an ego to get to the professional ranks – you have to be thick-headed and confident because you’ll have a lot of adversity to get through,” he explained. “You have to evaluate yourself as an athlete and make adjustments regardless of who you are and whatever skill level you have.

“I was never the most talented – I didn’t have any skill set that stood out as great,” he admitted. “But my hand-eye coordination was off the charts. I picked up every sport rather easily, and I would do it again even though the athletes are getting more specialized.”

Hendrickson was drafted 31st overall in the 1996 NBA draft by the Philadelphia 76ers. His basketball journey took him to four different teams across the United States – Sacramento, New Jersey and Cleveland were the others. He played in 114 games, averaging 3.3 points and 2.8 rebounds.

Before and during his basketball career, Hendrickson was drafted six straight years by MLB teams.

The first time was out of high school as a 13th-round pick in 1992 by Atlanta. The sixth came in 1997 when he was taken in the 20th round by Toronto. He played in the Blue Jays organization for three seasons from 1998-2000 while also playing in the NBA.

Once Hendrickson dedicated his career to baseball he moved quickly through the minor leagues to the majors.

Despite a rocky start versus the Mariners, he became a starter and finished his rookie season in 2002 with a 3-0 record and a 2.45 earned run average in 36 innings.

Hendrickson played for Tampa Bay, Los Angeles, Florida and Baltimore, finishing his career with a 58-74 record and 5.03 ERA. He made 328 appearances and 166 starts and finished with a total of 1,169 innings and 666 strikeouts. And that doesn’t even include numerous stops in the minor leagues to both begin and end his baseball odyssey.

And through it all, he had nary a multiyear contract – just one that included a second-year option.

“Every athlete is trying to survive. It makes it very challenging to come back and continue to perform,” Hendrickson said.

His challenges started at a young age.

…

Hendrickson was just five months old when his father, Thomas Hendrickson, died on Nov. 17, 1974, at the age of 31. A Washington State Patrol officer, Thomas was killed in the line of duty by a drunk driver.

That left his mother, Barbara, to watch over Mark and his older brother, Steve. Two years older than Mark, Steve would also eventually attend Washington State and watch over his younger brother in Pullman. Their grandfather helped instill a love of sports into the brothers, and they would play any and all sports as they grew up.

A natural lefty, Mark would grow from 6-foot-1 to 6-foot-7 between his freshman and sophomore year at Mount Vernon High School. That meant as long as he could learn to deal with his growth spurt, his youth soccer skills and point guard skills in basketball would be assets on the court and on the diamond.

As a sophomore at Mount Vernon, the Bulldogs were humbled by Battle Ground 95-63 for the State AA basketball title. They came back to win the championship the next year with a 59-52 victory over Battle Ground, then in his senior season were undefeated and repeated as state champs with a 56-38 victory over Shorecrest.

In baseball, the Bulldogs also won State AA titles in 1990 and 1992. The summer after his senior season while playing American Legion baseball, his team won the state tile and lost in the championship game of the regional tourney.

“We weren’t spoiled by winning, but we appreciated it,” he says of his high school days. “I remember crying after my senior year of basketball when we won the state tournament. I was sad it was done, and to that point I had spent 18 years in Mount Vernon.”

…

Success seemed to follow Hendrickson to Pullman, and he played considerably as a freshman in the 1992-93 season. He averaged 12.6 points and 8.0 rebounds as he was named to the five-member Pac-10 All-Freshmen Team.

The next season, the Cougars earned their way into the NCAA Tournament under Kelvin Sampson, who would depart Pullman after that year for Oklahoma.

In 1995 and 1996, Hendrickson would earn first team All-Pac 10 honors and help the team advance to the NIT both seasons under new coach Kevin Eastman.

Hendrickson finished his career as the Pac-10 active leader in double-doubles with 43 in 108 games and became the first Cougar to lead his team in rebounding all four seasons. Hendrickson concluded his basketball career by holding the school record in career field goal percentage (.567), while ranking second for career rebounds (927) and third for points (1,496).

Hendrickson also made eight appearances on the mound for the Cougar baseball team during his junior year in 1995 under new coach Steve Farrington, who succeeded legendary coach Chuck “Bobo” Brayton. The Cougars won the Pac-10 North Division title that season.

“I was ready for it emotionally,” he said of waiting until his third year at WSU to dive into the life of a dual-sport athlete. “College was an eye-opening experience. Coach Sampson was demanding, and it was good for me. Those were two years with a steep learning curve to really understand the commitment to basketball and the training involved. It was a big jump from high school.”

Hendrickson said he always considered baseball a summer sport, partly because he grew up on the rainy west side of Washington where the high school baseball season was essentially crammed from mid-April to the end of May. So even though he didn’t play collegiately his other three seasons at WSU, he honed his skills by playing semiprofessional baseball in the summers.

“Baseball started so early in college, then they would go south for a while,” he said of the collegiate baseball season which began in January just as league play in basketball was beginning. “And with basketball going as long as it did, (my college baseball career) didn’t amount to much. But I always played in the summers.”

He says now his desire to play professional baseball was “always there” when he was in college. But what the Cougs accomplished on the basketball court was more important. “Being a part of the NCAA Tournament was a big deal to me.”

…

When his WSU hoops career concluded in 1996, the Seattle SuperSonics were high on his list of potential teams to play for in the NBA. He was 5 years old when they won the NBA title in 1979, and in 1996 Seattle won the Western Conference title the same year Hendrickson was to be drafted.

Hendrickson remembers having a pre-draft workout with the Vancouver Grizzlies in the morning one day, then flying to Seattle for his workout with the Sonics that afternoon. Seattle had a pick at the end of the first round that he hoped to snag, but Seattle traded it away for two second-round picks.

“Because it was the Sonics and I was from that area, I had the best workout of any of my workouts,” he said of his hopes of being the 28th pick overall. “That crushed me. I really wanted to play for them.”

As it turned out, three selections later he was picked by the 76ers with the second choice of the second round. He had impressed the brass at Philadelphia during his final pre-draft workout, and ended up on a squad with No. 1 pick Allen Iverson out of Georgetown.

“I caught fire,” he said of his visit to Philly. “Any drill we were doing I just couldn’t miss. So I wasn’t surprised when they picked me, but I was pulling for Seattle for sure.”

Because his parents were both from York, he had a built-in fan base of family members his rookie year. He played in 29 games that season, then 48 the next season for Sacramento.

He also had two stints in New Jersey, including the final five games of his career in the 1999-2000 campaign. None of the teams he played on reached the playoffs.

“I was able to play well enough to play into a contract the rest of the year,” he said of his four years in the NBA. “But people don’t realize just how many people are trying to get into the league.”

…

While in the NBA, he played semiprofessional baseball in the offseason before signing with the Blue Jays on May 22, 1998. He spent time with A and AA minor league clubs in 1998 and 1999, and again in 2000 after he quit basketball.

He sometimes wonders what would have happened if he would have signed with the Braves out of high school, but knows he took the best path possible to the majors. He found out firsthand what the minor leagues are like but was thankful he didn’t go through it as an 18-year-old.

“That’s a brutal life. It’s survival of the fittest. There will be instruction, but they don’t give you instructions on the grueling grind of playing every day, living off of pennies and staying in hotels.”

After his third year in the NBA, Hendrickson was invited to the Arizona fall baseball league for top prospects and where scouts congregate. It was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up and he performed well, but he knew he had to quit the NBA to give him the best leverage. So early in 2000, his basketball career was over.

“I said, ‘I’ll see you at spring training, Toronto.’ And that’s all she wrote – I didn’t look back. I had to commit.”

He played for Syracuse in the AAA International League in 2001 and 2002 before getting called up by the Blue Jays.

The most innings he pitched in MLB came in 2004 with 1831/3 for Tampa Bay (10-15, 4.81 ERA), then pitched 1781/3 the next year (11-8, 5.90). His lone postseason appearance came in the 2006 National League Divisional Series while he was with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He appeared in all three games and gave up no runs in 22/3 innings, but the Dodgers were swept by the New York Mets.

“It’s all chemistry,” he explains of what makes teams into playoff contenders and champions. “Players have an inner circle where they can’t do anything wrong, so it’s very difficult to get them to buy into a team aspect when there is so much at stake individually.

“In baseball, you can’t cheat a 182-game season.”

Hendrickson also became the first pitcher in Toronto Blue Jays history to hit a home run, which he did against the Montreal Expos on June 21, 2003. He played in 2008 for Florida and 2009-11 for Baltimore. The Orioles extended contracts in 2013 and 2015, but he was released both times.

“You have to put the work in to stay, and it’s harder to stay than to get there,” he says. “You have to have the motivation every day. There is no guarantee for tomorrow.”

…

He says one of the lessons he absorbed and tries to pass along to others was to learn how to be a good practice player, and become very efficient in preparation.

“Getting drafted can’t be the climax, the euphoria and the ultimate dream,” he warns, likening it to climbing Mt. Everest. “You are up there for maybe two minutes, and now all of the sudden the real work begins because you have to get down the mountain.”

In 2015, Hendrickson settled back in York, a small town of about 45,000 in Southern Pennsylvania. He says when he retired, he cried in a parking lot because that part of his life was over.

“It was hard to do, and I see why athletes really suffer when they retire. That singular motivation, focus and attention to detail you have year-round is no longer there. I was walking around in a daze.”

Hendrickson, though, was motivated to get over it by the new-found time with his family, and working out and being healthy. “That lifestyle has never changed for me.

“It was a long time, and a lot of commitment,” he said of his time in collegiate and professional sports. “I always had the dream when I was a kid that I would play until I was 40 and then take it year-to-year after that. It’s a much different mindset when your body goes through the changes I don’t think the average fan understands. You have a lot of wear and tear on your body, and it comes down to trying to bounce back and play game-after-game-after-game. That’s the hardest part.”

After a year off, Hendrickson coached a couple of years in the Orioles organization, and for the most part was able to commute to his job in Aberdeen, Maryland. “I loved it when I was interacting with the players, but I was missing out. I just decided I couldn’t do it.”

So instead, he turned to interacting with his own kids by coaching his daughter’s basketball team. She’s 9 and in the third grade now, and one of his other daughters is 11 and helps coach. Even his 4-year-old is involved.

“It was probably the first time I’ve been on a basketball court in a team setting since my NBA days,” he admits. “It got the juices flowing again. I have way too much to pay forward.”

His 27-year-old daughter is married and has two daughters of her own.

“I have girls, girls and more girls,” he laughs.

In York, Hendrickson owns a company called Major League Properties, a firm that specializes in buying and renovating homes. He’s also doing some public speaking, and hopes to do more as he shares the lessons he’s learned in life.

He looks back fondly to his induction into the Washington State University Athletics Hall of Fame in 2016. In 2008 he was selected to the Pac-12 Conference Hall of Honor.

He’s still a big fan of the state of Washington.

“I enjoy watching the teams in the state, obviously the Cougs, but I’m not opposed to rooting for Gonzaga or UW,” he said. “It’s good to see the state of Washington do well.

“I miss Washington – I don’t get back to Pullman or Mount Vernon as much as I would like,” he added. “But it was a good spot to grow up for sure, and Pullman was a good college town. It was just big enough, and I can tell people when I went to college Washington State had the best basketball team in the region.”

Hendrickson said he isn’t sure if the number of NBA/MLB two-sport athletes will increase from 13.

Advances in technology, facilities and training regimens have changed the face of college and professional athletics over the years. But he knows it still comes down to a human component when determining if an athlete can handle the rigors of competing in two sports at a high level.

“Everything is better than it was, but athletes are still human,” Hendrickson said. “Committing to one sport full time year-round, I don’t how much better that makes you without taking some time off. I don’t foresee two-sport athletes in the future.”