Author Putsata Reang reflects on ‘Ma and Me,’ her accidental memoir, at Northwest Passages talk

Author and journalist Putsata Reangdidn’t set out to write a memoir. In fact, she didn’t consider herself a fan of memoirs before she found herself writing one.

Reang said so to a crowd of people Wednesday night at the Montvale Event Center, as she discussed her memoir “Ma and Me,” with Spokesman-Review columnist and Spokane NAACP President Kiantha Duncan. The event was part of The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages book club series.

Reang said she intended to write a book about the immigrant experience of her parents, who fled war-torn Cambodia in 1975 when she was just 11 months old. Reang’s original pitch transitioned into a memoir that explores Reang’s multifaceted identity as a gay Cambodian refugee raised in rural Oregon – as well as the strained relationship with her mother.

Reang grew up hearing the story of her parents’ escape from the coast of Cambodia to the Philippines on a crowded naval ship: how she was a sick infant at the time, how the ship’s captain thought she was dead and how her mother refused to throw Reang over the side as the captain demanded.

NAACP President and Spokesman-Review columnist Kiantha Duncan, on left, has a conversation with Putsata Reang about her memoir, "Ma and Me," which explores the legacy of trauma and cultural identity, and how Reang navigated her complicated upbringing, Wednesday, July 27, 2022, during a Northwest Passages event held at the Montvale Event Center. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN)

Hearing the story again and again left a profound mark on Reang. She said it led to her feeling like she was indebted to her mother, and needed to live her life to please her.

“So there was that added complexity of not only did she birth me, but she saved my life after that,” Reang said. “And I grew up internalizing that, thinking that I owed her my life because she saved mine.”

Like most people, Reang felt she needed to make her mother proud, but to such an extreme that she felt she needed to hide the parts of herself that would make her mother feel ashamed or disappointed.

She said she knew from an early age that she was gay, but hid it from herself and the rest of the world. It wasn’t until Reang took a job at the Seattle Times and found herself in the “gay mecca” of the Capitol Hill Neighborhood that she felt fully realized in that aspect of her identity.

“That was the first time that I let myself be who I was,” Reang said. “But the depths of the disappointment that my mom felt when I told her that I was going to marry my partner, a woman, was so painful to me.”

“What I realized in that moment, and I think that as children, is we get to this place at some point in the arc of our lives with our parents where a part of you has to die so that the rest of you can live,” Reang continued.

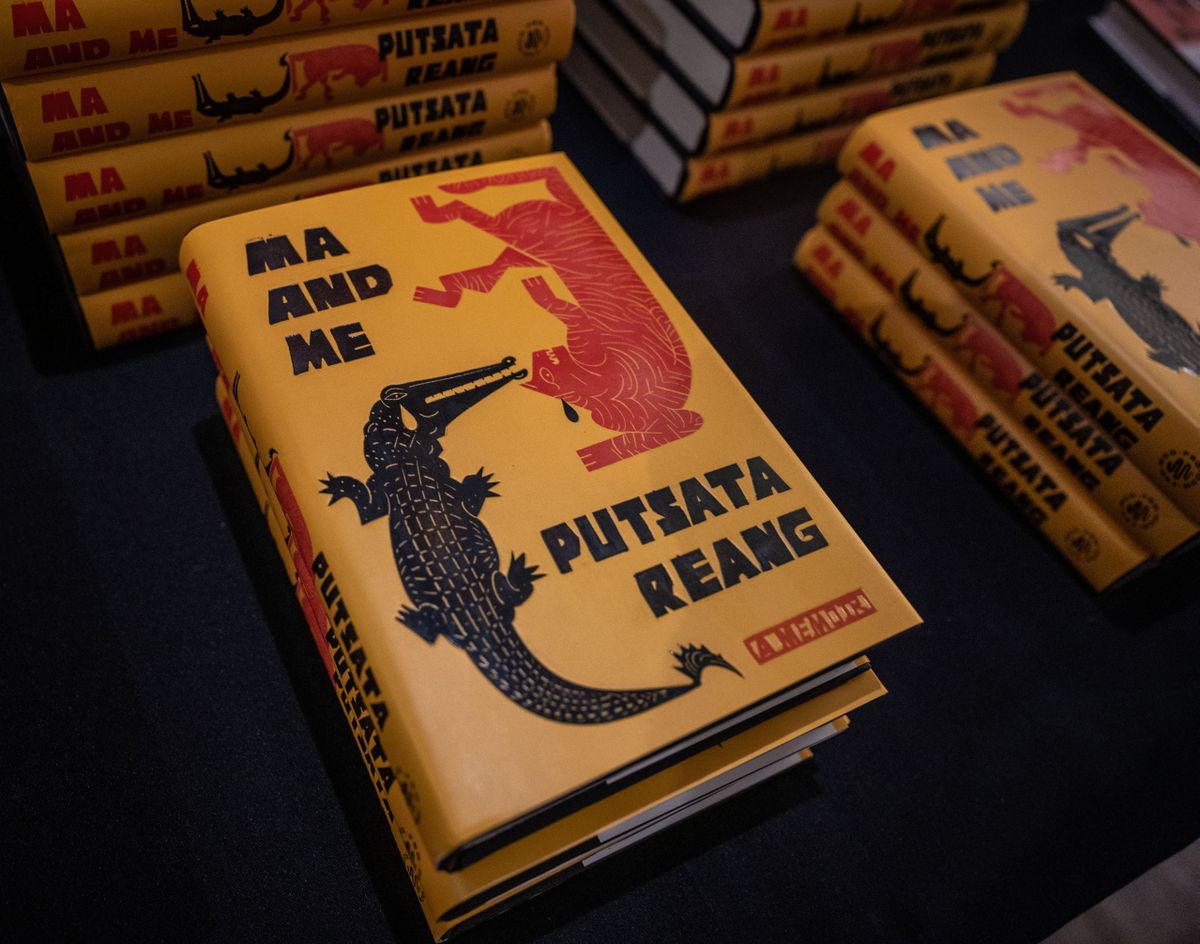

The cover of “Ma and Me” portrays a crocodile and a tiger, inspired by a Khmer saying: “Go in the water, there is the crocodile. Come up on land, there is a tiger.” Duncan and Reang discussed how that resonates with both of them as women of color, the sense of being stuck between a rock and a hard place, unsure of what threat may be around the corner.

Reang’s career as a journalist has taken her around the world but originated in the Pacific Northwest. Before she was published by the New York Times, Politico and the Guardian, Reang spent a year working for The Spokesman-Review after graduating from college.

Reang said it has been a sweet return to Spokane, even though she faced hardship during her time here in the late 1990s as a gay Asian-American woman. Although it was tough, she said it was the most formative year of her life, and it helped shape her into the woman she is today.

As gay women of color, Duncan and Reang reflected on their parallel life experiences. Both landed in Spokane knowing little about the city and faced hardships, but wanted to be a force for good despite it all.

“I think that there is something to say about pushing through those moments of stress, in those moments of discomfort, but there is also something to say about doing what is best for you,” Duncan told Reang.

“Had you not left, and had you not taken that position at the Seattle Times, and all those things, then we would not have gotten this memoir,” Duncan said. “This is really testament to how you did what you were supposed to do, because now you’re able to help an entire world of people because of your story.”