Most Camp Hope residents don’t want to leave, survey finds as City of Spokane wrestles with palatability of Trent homeless shelter

Heather Morse doesn’t usually sleep past around 8 a.m. these days. Any longer, her tent can feel like an oven.

Morse, who is from Spokane, has learned just how hot it can get having lived the past four or so months in the homeless encampment at East Second Avenue and Ray Street, known commonly as Camp Hope.

There is no “typical day” at Camp Hope, Morse said. Some days, she is responding to more incidents than usual as part of the camp’s security team. Other days, there’s nothing going on, or she’s helped remodel a tight common area that’s taken shape between her tent, a bus and a camper.

It’s the first time in the roughly 15 years she has spent parts of her life in homelessness that Morse has lived without dedicated power or water, she said.

“At first, I was ashamed of myself for how far I’ve dropped. I never thought that I would be in a tent city,” said Morse, 40. “I love it here, actually, now. I’ve been here since the end of February and I’ve met a lot of people here and I enjoy these people.

“If I had to be anywhere else, I’d want to be here and not anywhere else.”

Count Morse, then, among the people staying at Camp Hope who would not stay in a shelter if they have to be homeless.

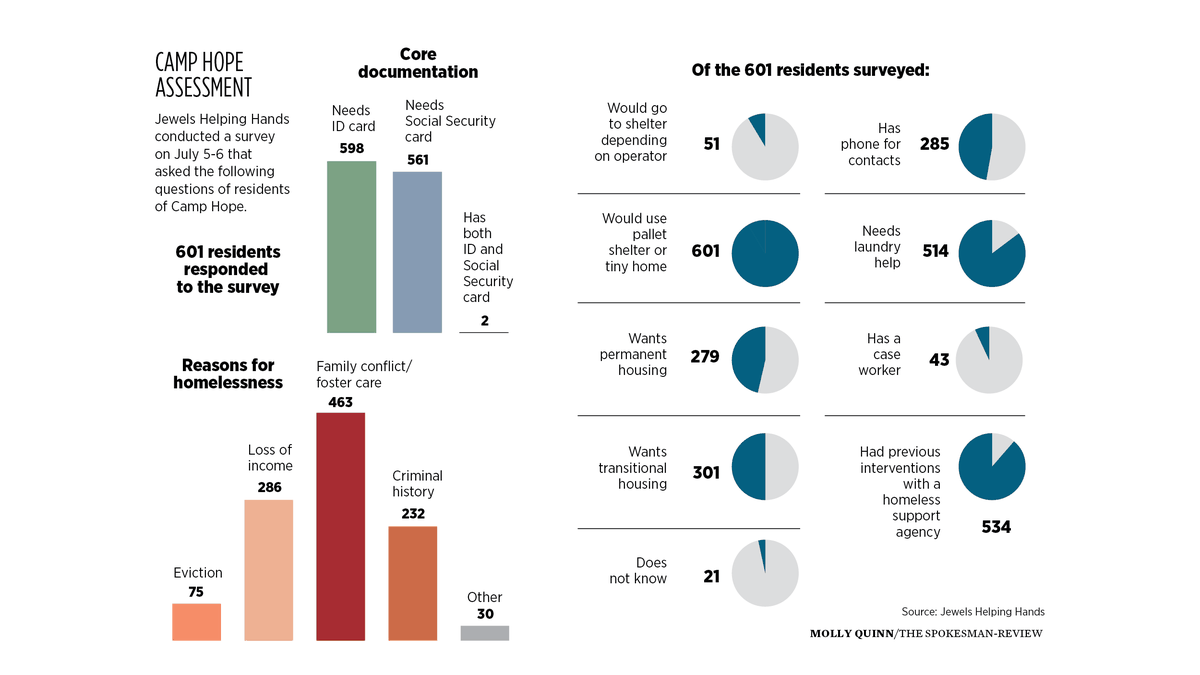

A census of Camp Hope residents recorded by Jewels Helping Hands, the homeless services nonprofit that oversees Camp Hope, recorded the preferences and issues facing 601 camp residents. The assessments, conducted July 5-6, found only 51 of the 601 reached would be willing to go to a shelter – depending on the operator.

“I personally wouldn’t go,” Morse said, “but if it would help other people that are here and other people here would want to go, then I would be super happy for them, but it’s not something that I want.”

Those sentiments conflict with the hopes of Spokane city officials that a new low-barrier, 150- to 250-bed shelter on East Trent Avenue is part of the solution for relocating people out of Camp Hope and into more secure living situations. Low-barrier shelters don’t impose certain rules like sobriety on guests.

The city administration has earmarked the Guardians Foundation to operate the facility at 4320 E. Trent Ave. with the goal of opening by August. City officials are still looking at options for providing social services to shelter residents, however.

Even if the Trent shelter does open in August, there is no timeline at this point for when people will have to move out of Camp Hope, according to city and state officials. In other words, the camp won’t have to disband after Trent opens.

“If that’s what happens, that’s what happens. I would never go to it,” Morse said. “I would still be out here or wherever else I could be.

The Trent shelter is just part of the city’s plan to relocate people out of Camp Hope, which evolved from a protest this past winter outside of Spokane City Hall demanding more shelter for the homeless.

After the city disbanded the protest in December, the camp sprang up at the corner of East Second Avenue and Ray Street where it has grown to what it is today.

The state Department of Commerce has offered $24.3 million to support efforts by the city and neighboring jurisdictions to get people out of Camp Hope. The funding is part of $144 million offered to five counties through the state’s Rights of Way initiative to move people out of state rights of way and into better living situations.

Earlier this month, the city submitted a spending plan for an initial approximately 30%, proposing to use $7.5 million for assessments and case management of Camp Hope residents, purchasing and rehabilitating a Sunset Highway motel for affordable housing, and providing for 30 two-person transitional living pods at the Trent shelter.

The Jewels assessment recorded 534 people who reported they’ve had previous interventions with a homeless support agency.

“Most of them have been kicked out of their shelter. That’s just the real reality,” said Julie Garcia, executive director of Jewels Helping Hands. “They’ve visited these shelters before. What happens if you’ve been kicked out of one or had a really bad experience? You’re not going to go back. Without trust, they’re not going to go anywhere.”

‘A place to exist’

Camp Hope, now reportedly the size of a small village, does not have any handwashing stations.

Garcia said there aren’t enough portable toilets on site; the ones they do have are supported by the Empire Health Foundation, while the city has provided three dumpsters.

The water supply is a mix of donated bottles or what’s available through the week in two tanks that can collectively hold 900 gallons. Garcia said camp facilitators pay a neighbor to use their water three times per week, filling the tanks with a hundreds-foot-long hose line.

There’s a single lane going through the center of the camp for emergency or other vehicles going in and out. The exterior facing I-90, meanwhile, is walled by campers.

This is something of a protective measure, Garcia said, as Camp Hope tents have been hit by paintballs, pellet guns and bear spray.

“This camp is growing faster than we can do anything about, mostly because they’re clearing out people from downtown, and everybody just comes here. Literally, there’s no space. We’re out of room here,” Garcia said. “This is not a shelter. This is just a place to exist on bare minimal stuff. We’re a nonprofit with no funding.”

Conflicts also arise within the camp itself – such is the nature of hundreds of people sardined on one residential block, Morse said.

“Of course there’s going to be conflict and there’s going to be problems that arise,” she said. “But for the amount that does, I think it’s pretty good for the amount of people that are here. There’s problems here, but it’s not as bad as it’s being made out to be.”

Jessica Chavez feels out of place at Camp Hope.

The 36-year-old from Spokane said she ended up at Camp Hope when she was evicted after a relative she was staying with overdosed. Living in Camp Hope is “scary for the most part,” Chavez said, due to the fighting she’s heard take place.

“I’ve already been to all of the shelters in town,” said Chavez, who lives at the camp with her dog, Lilly, “so I guess this would have to be it.”

Kristen Gerloff, 41, had to leave her previous living situation due to a family conflict. Family conflict/foster care was recorded on the Jewels assessment as the most common reason for why people at Camp Hope are homeless.

Gerloff and her fiancé, Steven, had nowhere else to go because Steven didn’t have his state identification. She said a shelter wouldn’t work for her, as some do not accommodate work schedules and separate couples.

Now that the two have their IDs, Gerloff has plans to move out of Camp Hope soon, after arriving in May.

“It’s kind of a struggle at times. Lots of fights. Lots of drugs,” she said. “People just need to give other people a chance. They don’t know other people’s situations until they walk in their shoes.”

Danny Taylor described himself as the “boss” of Camp Hope.

The 39-year-old, who moved to Spokane in May 2021, has a bus and RV at Camp Hope.

The backs of both vehicles also serve as the walls of a makeshift shower usable, Taylor said, by first heating up water in a jug and hanging it up high.

Taylor said getting a job is difficult with his criminal history. Having lived in shelters before in other states, Taylor said it’s challenging not having a guaranteed bed.

“You can’t ever get stable. You got to be in by this time, you got to be in by that time to get a bed,” he said. “You really don’t know if you’re going to get a bed if you’re not there at this time; there’s only so many beds, usually.”

Moving forward

Of the 601 people tallied with the Jewels assessment earlier this month, 598 do not have any ID, while 561 do not have a social security card.

All 601 reportedly indicated they would use a tiny home or a pallet shelter. When the city sought proposals from potential agencies to run the Trent shelter, Jewels submitted a plan that included pallet shelters.

“It’s time to stop doing it the way we always have,” Garcia said, “because all scientific data and best practices show that congregate shelters are the worst idea for people experiencing homelessness.”

Nevertheless, Garcia said she does believe the city needs the Trent shelter – but without a service provider, it’s “an overpaid warming center.”

“I don’t really know what the answers are at this point, but the politics is talking about what they’re going to do with all of this money,” Garcia said. “The basic needs of these folks are not being met.”

City spokesman Brian Coddington said city officials are working on ways to encourage Camp Hope residents to move into the Trent shelter more comfortably.

“One of the things we’ve heard about the WSDOT camp is they’ve created a sense of community,” Coddington said. “A community is not a big group; it’s more of smaller units within the camp there, so we’re looking for ways to incentivize people to move as a unit into that location and keep them together in a smaller, defined way.

“We’re also looking to provide more private or semi-private space as well, which is something we’ve heard that’s important.”

In the city’s proposal to the Department of Commerce for the initial round of Right of Way funding, Jewels Helping Hands is listed as one of the agencies that would help out with the onsite assessments of Camp Hope residents.

Other agencies include the United Way, Spokane Neighborhood Action Partners, Providence Clinic, Frontier Behavioral Health, Spokane Regional Health District, Compassionate Addictive Treatment, CHAS Medical Street Outreach, Revive Counseling and Wear Law Office.

The assessments, estimated to cost $500,000, would include ID and documentation assistance, transportation and “immediate and short-term alignment with housing and shelter options that are available,” according to the proposal provided to The Spokesman-Review.

“The Trent opening and the assessments of people moving are not totally tied together,” Coddington said. “If people are willing to move right away, they can go into the Trent shelter, be assessed there for next steps.”

With the initial Commerce funding, the city proposed to use much of it – $6.5 million, as proposed – for the purchase and rehabilitation of a Sunset Highway motel to create 88 affordable housing units for 100 to 110 people.

Finally, in addition to the 30 two-person transitional living pods, another $500,000 would go to expand shelter infrastructure “for more permanent restroom, shower, laundry, and ADA accessibility for sustained use.”

The city’s submission was signed by Mayor Nadine Woodward, City Council President Breean Beggs and council members Lori Kinnear and Zack Zappone. No decisions have been made on the proposal, said Tedd Kelleher, managing director of the Housing Assistance Unit at the Department of Commerce.

There’s no guarantee Spokane County is in line to receive the full $24.3 million. Kelleher said if one community moves faster than another, the Department of Commerce reserves the right to reallocate money to support efforts with greater progress.

The state won’t be able to make that call until all of the proposals for shares of the $144 million are submitted. The deadline is Thursday.

“We’re still in conversation with each of the five counties about what does really aggressive look like given available resources and infrastructure,” Kelleher said.

“This site is a little different than some of the other communities because this is one large site as opposed to smaller ones, so we’re still working out what that looks like.”