‘We’re not doing enough’: Latest point-in-time count offers snapshot of rising homelessness in Spokane County

A recent census of Spokane County’s homeless populations has indicated an approximately 13% rise in homelessness over the last complete tally conducted two years ago.

While a lack of housing is a factor in the region’s rising homelessness rates, approaching it as a supply-and-demand issue is not the answer – especially since the problem doesn’t have a singular cause or solution, said Matthew Anderson, an associate professor and director of the urban and regional planning program at Eastern Washington University.

“There’s so many mediating variables that it tends not to really happen. Seattle, for instance, has been doing this, but prices have never been higher,” he said. “The time it takes … it could be a year or more later. A lot’s happened in that year or more later.”

Anderson offered his conclusions as one of the coordinators behind this year’s point-in-time-count, the latest annual census of Spokane County’s homeless population as required by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Researchers and volunteers focused this year’s count on where people were living and sleeping Feb. 24. Approximately 140 volunteers formed a team helmed by Daniel Ramos, who runs the city’s Community Management Information System; Shiloh Deitz, community data coordinator for Spokane Public Library; Anderson; a number of EWU students and city officials.

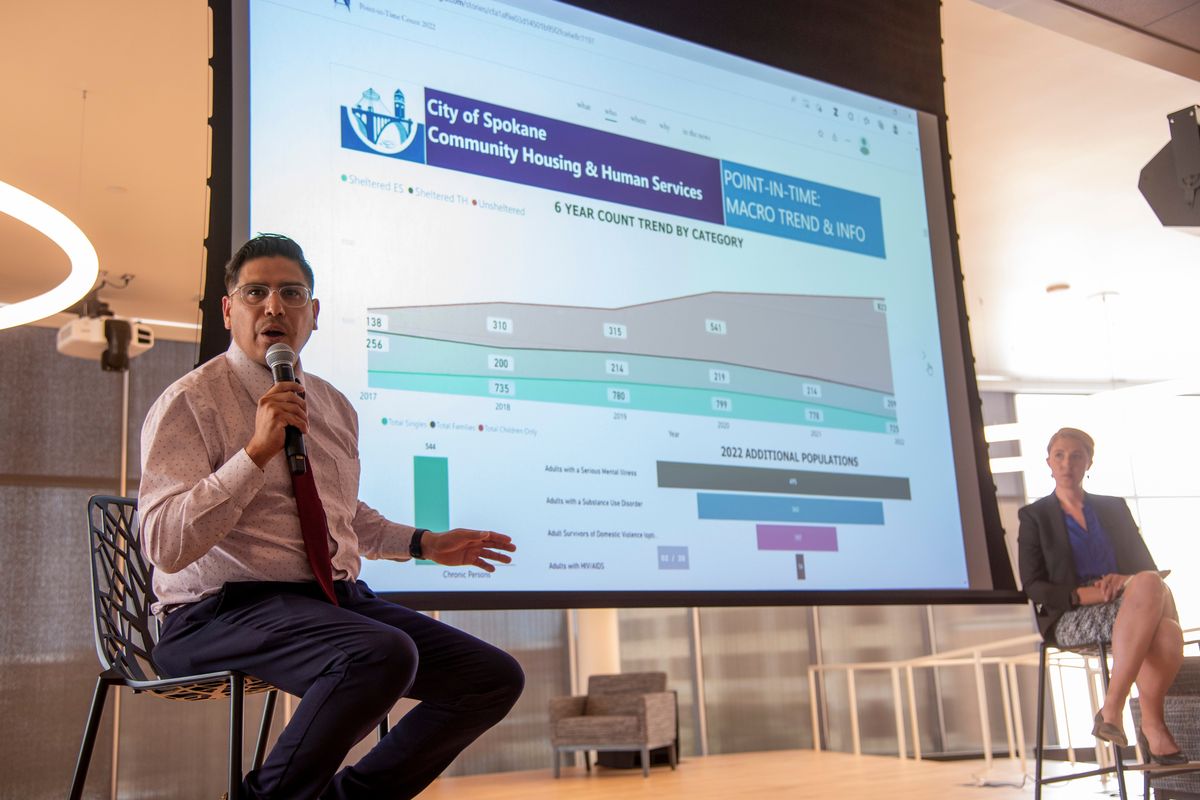

The results, detailed during a presentation Wednesday at the downtown Spokane library, tallied 1,757 people out of 1,513 households that were homeless.

That’s up from the 1,559 people in 1,244 households counted in 2020, the last time evaluators could conduct a complete Point-in-Time count, as the COVID-19 pandemic restricted 2021’s research to sheltered individuals only.

Of the 1,757 tallied, 934 were sheltered, with 725 in emergency shelters and 209 in transitional housing.

The other 823 were unsheltered, up 52% from the 541 tallied in 2020.

By the numbers

Ramos said HUD classifies homeless persons into three groups: singles, families and “children-only households,” or households made up of persons under 18 years old.

Singles accounted for 1,460 of the 1,757 persons documented. Individuals from children-only families accounted for just 10.

The number of veterans tallied with this year’s count, or lack thereof, was a bright spot of the report, Ramos said, as veterans only represented 6% of the tally. Approximately 11% of the county’s population is veterans, he said.

“Which means there’s some work that’s been done over the last couple of years,” Ramos said, “and it’s working.”

A majority of the people documented for this year’s count were living in Spokane before they were homeless, according to the data.

Of the 74% of unsheltered individuals who indicated they lived in Spokane County before becoming homeless, 79% said they lived in Spokane. Another 13% indicated they lived in Spokane Valley.

On Feb. 24, however, 260 of the 823 unsheltered individuals were living in a homeless encampment, up from the 74 counted in 2020.

Several dozen of the unsheltered were recorded on or near state Department of Transportation land along East Second Avenue and Ray Street that has grown into the Camp Hope homeless encampment, which is occupied by upward of 600 people, according to a recent count. That land was unoccupied during the 2020 point-in-time count, according to the data.

There were 213 people documented as living on the street or sidewalk, up from 156 (approximately 37%) in 2020. Another 155 were found in RVs, vans or cars, similar to the 149 documented two years ago.

‘We need a lot more from the top’

Unsheltered individuals documented with this year’s count were asked a number of survey questions, including why they didn’t plan to sleep in an emergency shelter Feb. 24.

Approximately 44% of people cited reasons related to “safety/fear of violence,” according to the data, with “privacy” (38%) “anxiety” (31%) and “rules” the next most-common responses. People were allowed to choose more than one answer.

In evaluating the causes of homelessness, the point-in-time count differentiates between “structural determinants,” like housing and the job market, and “individual risk factors,” such as mental health and domestic or substance abuse.

The data suggests, however, that while substance abuse and serious mental illness are factors, there have not been major increases in those areas that correlate with the county’s rise in homelessness.

The report does outline a relationship between the number of homeless individuals tallied with point-in-time counts over the years versus the area’s housing affordability index.

The housing affordability index measures a median-income household’s ability to afford an average-priced home. A higher number means more affordability.

In Spokane County, that number has trended downward over around the past five years to its lowest point since 2009, according to the data, but, the 1,757 people tallied this year is the highest the count has been in that span.

“We can’t say that this is exact causation, but it’s interesting the relationship we see here between those two things,” Deitz said. “With the housing affordability index and the point-in-time count, what is likely happening is that more and more people are getting squeezed out of the housing market. Going to the rental market, there’s less and less available.”

Asked about the primary reasons they became homeless or what services they are in most need of, homeless individuals who responded to the point-in-time survey indicated housing in some capacity, whether it’s a lack of affordable housing or the need for permanent housing.

Spokane is “not unique or special” in regards to the lack of affordable housing, Anderson said, as the problem is similar in places with higher costs of living across the country.

“Getting people out of homelessness today is just part of the picture. We’re not doing enough to prevent people from becoming homeless tomorrow,” he said. “What that would look like: a lot more subsidized housing and federally funded mental health institutions, which we had a lot more of until the 1980s.

“We really need a lot more from the top to address why the streets are becoming so unsafe,” he continued.