Senmut’s story: The man behind the old Spokane Masonic Temple’s stone busts

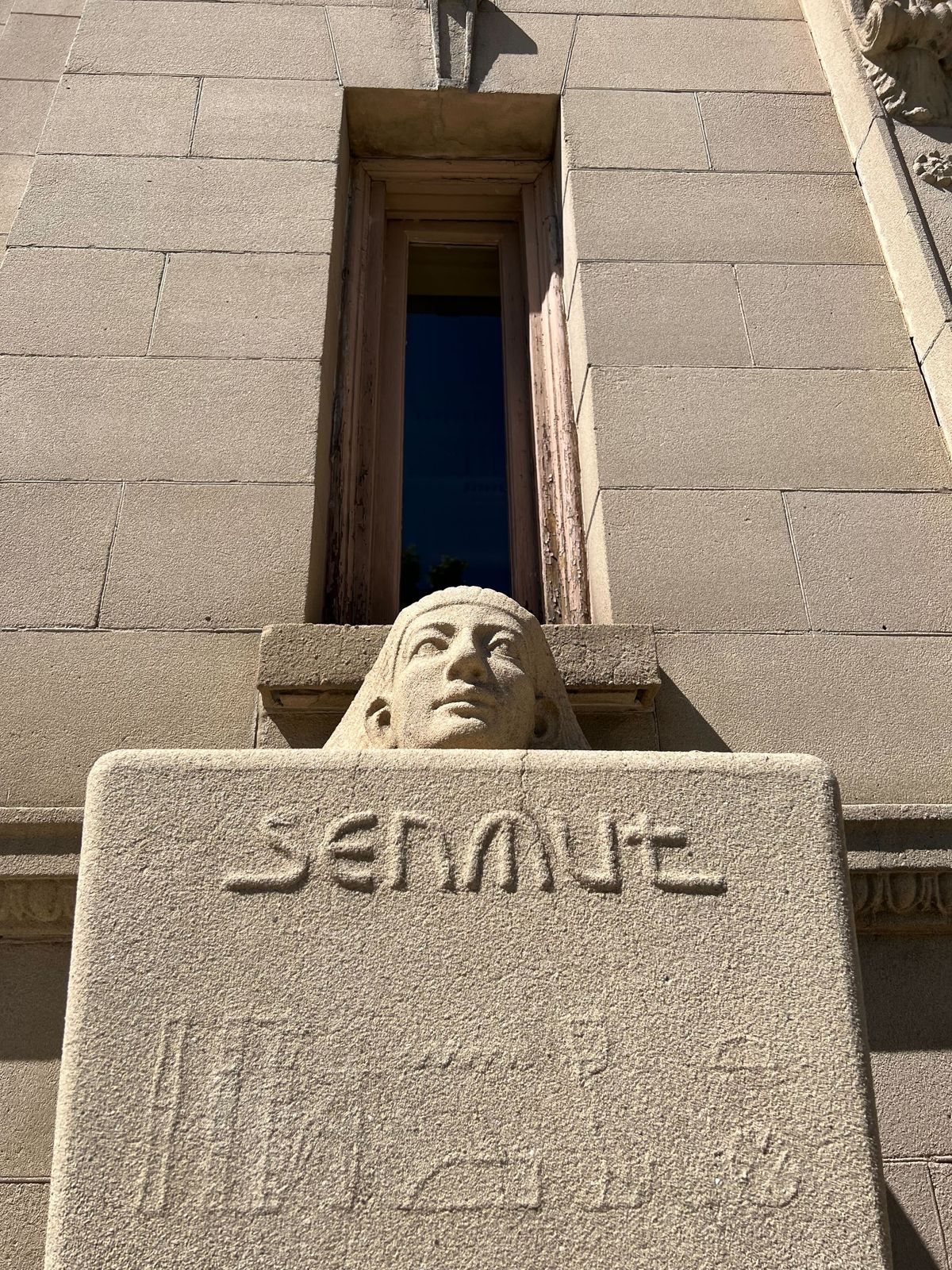

Senmut, the famous Egyptian architect, guards the south entrance of the old Masonic Temple on Riverside Avenue. (Quinn Welsch/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

The wide open halls of Spokane’s old Masonic Temple are mostly empty except for the occasional event bookings. But an ancient guardian maintains a watchful gaze over Riverside Avenue’s Historic District, almost a decade after the Freemasons left the building.

His name is Senmut.

Originally built in 1905 on the edge of the Spokane River and somewhat ironically located across the street from the Freemasons historic rival, the Catholic Church’s Cathedral of Our Lady of Lourdes, the building is a wonder of Neoclassical-Revivalist architecture, adorned with ancient symbols and inscriptions inside its approximately 118,000 square feet. Senmut, an ancient and powerful architect from almost 3,500 years ago, is one of them.

Four stone busts of Senmut guard each of the two south entrances of the building, which gently arcs around the curve of Riverside Avenue.

The Freemasons left the building in 2013 when it was apparent that it was too large for the declining numbers of Masons and associated fraternal organizations to fill. The building was sold the same year for $1.1 million to Australian businessman Greg Newell, president of Power Handling. The building is home to the company’s offices, as well as event hosting company Riverside Place.

While the temple and its secrets are closed to the public outside of private events, Senmut remains one of the most public-facing questions of Spokane’s old Masonic Temple.

Who was Senmut?

Senmut: The man, the myth, the legend

Senmut, often spelled as Senenmut and translated to “mother’s brother,” was one of ancient Egypt’s most famous architects most known for his work at the height of the ancient empire’s power.

Despite humble origins, Senmut’s story is one of bootstrapping success and a rise through the highest rungs of power. Although he was born to what might be considered a middle class family, Senmut made a name for himself in one of the ancient Egyptian empire’s most revered roles: architect.

He is perhaps best known for his close association Queen Hatshepsut, who ruled the empire while her nephew and heir to the throne was still a child. Senmut, who likely began his architecture under the rule of her husband, Thutmose II, was considered one of the queen’s closest companions, her most trusted adviser, and is rumored to have even been her lover and the father of her daughter Neferure, who he mentored, according to some historical accounts.

After the death of her husband, Thutmose II, Hatshepsut was named regent. But just a few years later, she proclaimed herself pharaoh – even portraying herself as a male god king – in what some early Egyptologists considered a conspiracy to wrest power from her young nephew, Thutmose III, according to the Smithsonian. More recent theories suggest her rise was a political move to protect the young heir, the Smithsonian said.

Hatshepsut was one of the few women to rule Egypt during an era of peace and prosperity. All along, Senmut was by her side, advising her and rising through the ranks of power.

The queen’s architect led the most important building projects during her rein. Among the nearly 100 different titles Senmut earned in Egyptian high society, he was named “overseer of temples” and lead the construction of the queen’s Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri, one of the most ambitious projects of the time. Senmut also constructed two 100-foot obelisks – the tallest at their time – in honor of Hatshepsut.

As for himself, Senmut had what the Smithsonian described as a “staggering” 25 personal monuments for a nonroyal. Although Senmut built a tomb for himself near Hatshepsut’s in the Valley of the Kings, the famous Egyptian architect’s fate is unknown.

Following Hatsheput’s death, there was an apparent attempt to deface many of her monuments and essentially “rewrite history” during her nephew Thutmose III’s reign.

Senmut’s legacy lives on in Spokane.