We the People: In an era of great polarization, is the preamble based on an eroding idea?

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: The U.S. Constitution starts with the words “We the People.” What does “We the People” mean?

“We the People” is one of the best-known phrases in the American political lexicon. They are the first three words of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States and propose that the “people” should be the driving force behind what government does or doesn’t do.

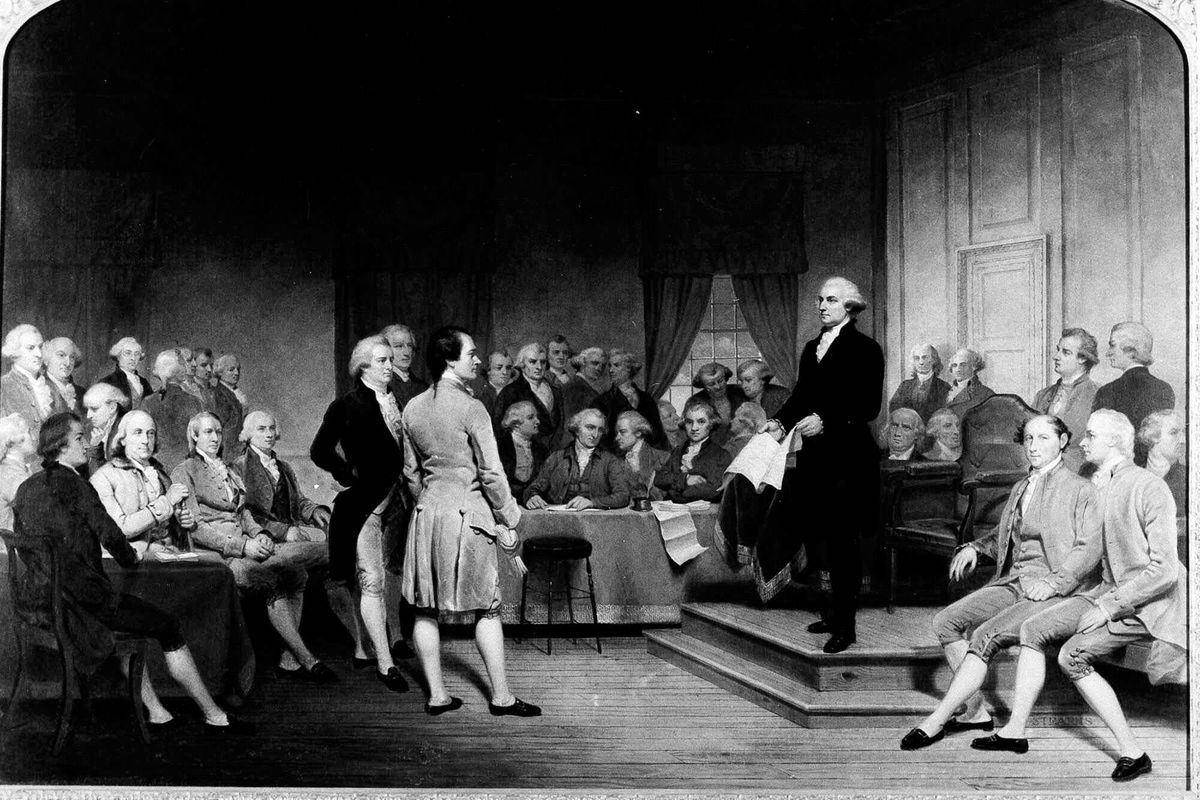

The phrase was written by Gouverneur Morris, one of the most active and vocal of the 55 delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He initially proposed that the preamble begin “We the States,” which was rejected in the final draft in favor of the idea that the Constitution should aim to form a unified nation rather than a treaty of separate, sovereign states like the failed “Articles of Confederation.”

But who are the “people?”

For the purpose of ratifying the Constitution, the “people” were defined as free white men who owned property. Over time, the franchise was expanded through a series of amendments to the Constitution to include African American men (15th Amendment; 1870), women (19th Amendment; 1920) and people 18 years of age (down from 21) and older (26th Amendment; 1971). Native Americans were granted the right to vote in 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 eliminated instruments of voter suppression such as literacy tests, expanding the group even further.

When the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United vs. FEC (2010) that corporations have a First Amendment right to make independent expenditures in political campaigns, the definition of personhood for political purposes was expanded again. Not all changes to voting laws have been inclusive. For example, in 2013 the Supreme Court struck down some portions of the Voting Rights Act. As the U.S. Congress considers the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021 and a number of states debate the topic of voting rights, it is clear that the question of the meaning of “We the People” is far from settled.

On the civics test administered by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, among the acceptable answers to this question are “Popular Sovereignty,” “Consent of the Governed,” and (as an example of a) Social Contract.

Popular Sovereignty is the principle that government gets its authority through the consent of the governed through their elected representatives. Thomas Jefferson proposed this idea in the Declaration of Independence in 1776 when he wrote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident (that) Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The question of what “consent” means is, at best, ambiguous. Does consent connote simply the opportunity to participate in the political process even if that opportunity is not exercised (“implied consent”), or does it mean active participation through voting or other political activities? Is majority rule necessary for consent to be legitimate?

In pondering the idea of consent, it is instructive to remember that the Constitution enshrined several anti-majoritarian features into the Constitution such as the Electoral College for Presidential elections and the fact that each state, regardless of population, receives two seats in the U.S. Senate. These provisions mean that small, predominantly rural states receive disproportionate representation in federal elections and some of its institutions.

For instance, California’s population is roughly equal to that of the 22 smallest states. Since each state receives the same number of seats in the Senate, the result is that California has two Senators while the 22 smaller states send a total of 44 members to this congressional body. Further, what does consent of the governed mean in practice when Joe Biden received over 80 million votes in the presidential election of 2020 but that these votes represented only about 30% of the voting age population in that year?

A frequently overlooked meaning of “We the People” discussed at the Constitutional Convention was the creation of a Social Contract. This idea, popularized by political philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau during the “Age of Enlightenment,” is that democratic governments come into being because people are willing to give up some of their freedoms and agree to follow certain laws in exchange for the security and protections offered by the state.

Locke and others recognized that as individuals, people might naturally prefer absolute freedom to do what they wish. The idea of social contracts recognizes that human societies are greater than the sum of the parts. This is the idea behind James Madison’s famous sentiment in Federalist Paper No. 51 that “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Madison believed that people willingly exchange some freedoms in the name of the collective interest. Social contracts establish rules and norms that can be both explicit, as in laws, but also implicit, as in behaving in a civil manner in the public sphere.

Contemporary politics in the United States is obviously highly polarized and divisive. This is partially owing to disagreements related to “hot button” issues such as gun laws, abortion and immigration.

But to a greater extent, the discord gripping the nation is a result of a battle between different narratives regarding the future of America.

These are not policy differences, which might be open to bargaining and negotiation. Rather, it represents an existential divide in which each side sincerely believes that the other is trying to destroy America.

To what extent does the current state of American politics make the idea that “We the People” are engaging in a social contract quaint and outdated?

Steven Stehr is the Sam Reed Distinguished Professor in Civic Education and Public Civility at Washington State University in Pullman. This article is part of a Spokesman-Review partnership with the Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University.