Democrats’ elections bill offered voting changes and more

The sweeping elections bill that has collapsed in the Senate was about far more than voting.

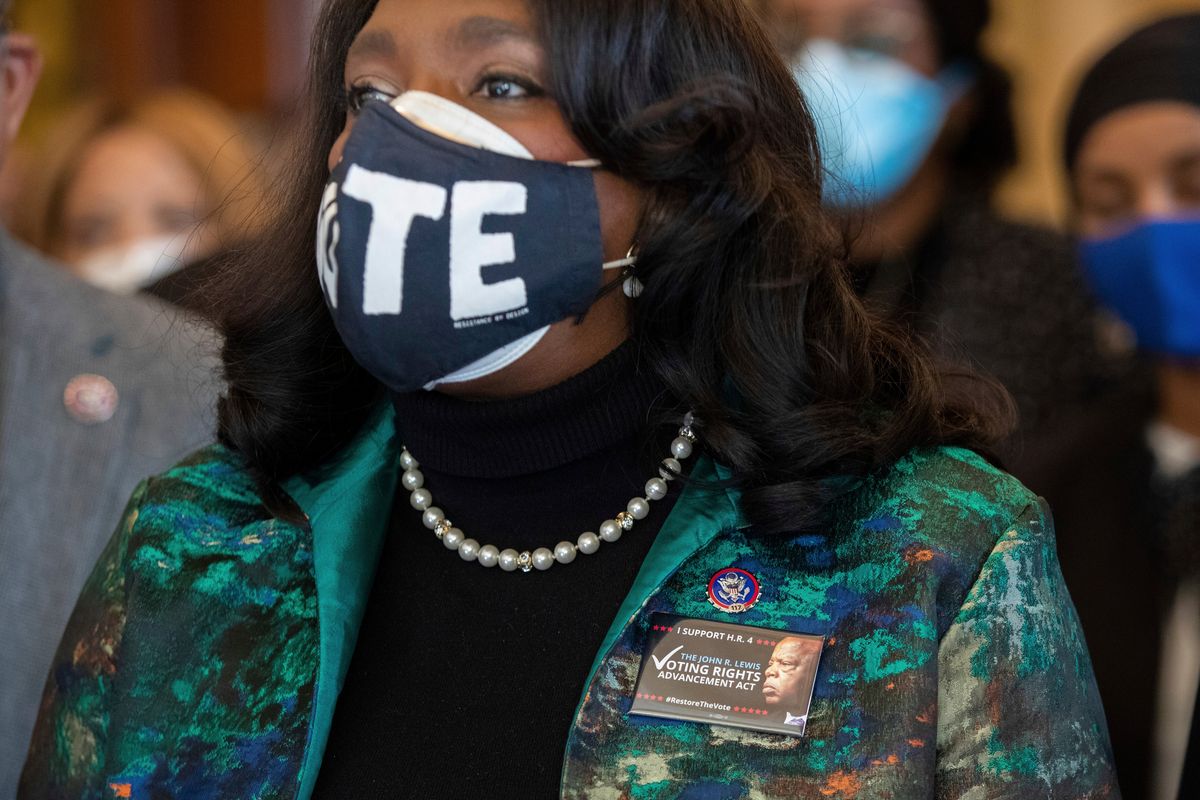

The Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act would have created national automatic voter registration, allowed all voters to cast ballots by mail and weakened voter ID laws. It would have banned partisan gerrymandering and forced “dark money” groups to disclose their major donors.

The legislation was an effort by Democrats to pass a major overhaul before the November elections. It was a response to what voting advocates say is an effort by Republican-led states to make it harder for Black Americans and others to vote.

When two Democratic senators refused to join their own party in changing Senate rules to overcome a Republican filibuster, the outcome Wednesday night was a stinging defeat for President Joe Biden and his party, coming at the tumultuous close to his first year in office.

“I am profoundly disappointed,” Biden said in a statement after the vote. Still, Biden said he was “not deterred” and he pledged to “explore every measure and use every tool at our disposal to stand up for democracy.”

A look at what was in the bill:

Voting protections

Advocates say new voting protections would counter a wave of recent restrictions passed in 19 states and fueled by Donald Trump’s lies that he lost the 2020 presidential election due to voter fraud. No significant fraud was found by Trump’s Department of Justice and by repeated independent investigations.

The bill called for automatically registering citizens to vote in every state, required that all states allow anyone who wants to vote by mail be able to do so, and said that mail ballots postmarked by Election Day could be counted as long as they arrived within seven days of the close of polls. It would have required a minimum number of drop boxes where voters could deposit mail ballots and let convicted felons vote after they have been released from prison.

The measure would have allowed documents such as a utility bill to serve as identification for voting.

Election administration

Many of the bill’s voting provisions have been Democratic dreams for some time. Recent additions were aimed at what some experts say could be even a greater threat to democracy than restrictive voting laws.

Trump has encouraged supporters to run for positions overseeing elections as he continues to claim the 2020 election was tainted. There are concerns that his supporters could try to throw future elections or impede the vote counts by nonpartisan election officials.

The bill would have made interfering with the vote count or failing to accurately report the results of that count a violation of the Voting Rights Act. It would have made it possible for nonpartisan election officials to sue if they were removed for partisan reasons, mandated a paper record trail for all ballots so they could be easily recounted and created cybersecurity standards for election machines.

A separate push in Congress to amend the 1887 law that lays out a complex procedure for counting votes in the Electoral College has attracted some Republican interest. The Senate bill was silent about that subject.

More than voting

The bill would have banned partisan gerrymandering — the act of redrawing political maps to make it easier for one party to get its representatives elected. Such a ban is a Democratic priority. Because Republicans control more state governments than Democrats do, the GOP has been able to exploit gerrymandering more than Democrats recently, though the two parties are close to parity in the latest, once-a-decade redistricting process.

On campaign finance, the bill would have required any entity that spends more than $10,000 on elections to disclose its major donors. This was an attempt to pierce the veil of “dark money” that a Supreme Court ruling helped allow into campaigns. The bill would have allowed states to offer matching funds for small-dollar donations to races for seats in the House of Representatives.

Voting Rights Act

The part of the bill named after Lewis, the late civil rights leader and Democratic congressman from Georgia, would have updated the Voting Rights Act and was a direct response to a Supreme Court ruling that weakened the law’s oversight of states with a history of discriminating against Black and other minority voters.

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the formula used to determine whether a state, county or city has such a history of discrimination that it needs to get permission from the Justice Department before changing voting laws and redrawing political lines. At the time, nine predominantly Southern states, including Republican stronghold such as Alabama, Louisiana and Texas, and dozens of counties required such federal approval.

If that requirement was still in effect, civil rights groups say, many of the most controversial voting law changes passed last year may never have happened. It may have also limited Republican gerrymandering in some states.

The bill would have provided a new formula to start the “preclearance” process. It would have strengthened provisions of the Voting Rights Act to counter a Supreme Court decision last year that made it harder to sue over laws that hamper minority voting.