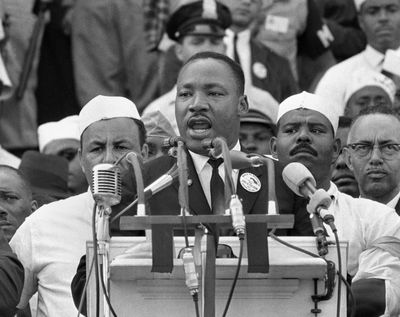

We the People: Martin Luther King’s fight for equality for all changed the way America protests

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Martin Luther King Jr. is famous for many things. Name one.

As one of the giants of the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. rose to worldwide prominence for his demand for equality of all people through nonviolence and religion.

Born in 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia, much of King’s advocacy has its roots in those who came before him. The civil rights movement has strong ties to the Pan-African movement, which dates back to the turn of the 20th century. One of the leading Pan-African activists, W.E.B. DuBois, moved toward equality at a pace many were not ready for, calling for economic equality and self-actuality. But many activists were skeptical of DuBois’ approach. Angela Schwendiman, Eastern Washington University’s Senior Lecturer and Program Director of Africana Studies, noted that DuBois and the Pan-African movement “inevitably culminated” in the civil rights movement, and that DuBois’ ideas “transcended time with the help of Dr. King.”

“DuBois said we need the right to vote, civic equality and economic incentives,” she said. “And we need education, which would open up opportunities for everybody. He was about self-actualization, that we have the right to demand to be treated as human beings, and to realize our full potential, as part of humanity. And when he proposed that, that was considered radical at the time.”

But racism toward Black people became more prevalent throughout the 1940s and 50s, and after the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling in 1954 found that school segregation was illegal, the civil rights movement picked up speed. A year later, King first garnered attention for his efforts during the Montgomery bus boycott, one of the key protests that moved attention to the civil rights movement to the south.

King effectively wrote pieces to advocate for equal bus rights, organized nonviolent protests and delivered speeches during the 13-month boycott. Along with traditional activism, King updated DuBois’ message by taking pages from the Bible.

King’s message of equality for all people rests in his religious beliefs that “everyone is a child of God.” With many white Americans identifying as Christians, religion was an easy way to bridge the gap; King adopted many of his father’s pastoral speaking styles and talking points to influence people. Schwendiman described King’s talking points as “Christian humanism,” a particular route not seen yet by activists of the Civil Rights Movement.

“King comes in with this Christian humanism, this belief that we are all children of God, we all come from the same creator. And therefore, we’re all equal,” Schwediman said. “We’re all of his children, once whites and Blacks begin to feel that they are all children of God. That was empowering, and that meant that Black people were no longer going to accept whites treating them like this.”

Religion also helped King create effective activists through a church-based network. He was the founder and first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights organization founded in 1957 with a goal to eradicate issues in the community such as racism.

Fusing religion and fellowship, Black churches were an easy messaging system to disperse news of information and political protest. Many African Americans attended Sunday church services and could also attend brainstorming and information meetings about protests. Many protesters of the Montgomery bus boycott were members of the church networks.

“The civil rights movement looked very different before organizing took place in the basements of the churches,” Schwendiman said. “These things didn’t happen overnight. They were meeting in the churches, they were talking about these things, forming what they call ‘communities of congruence.’”

King used many political and social pressures of the 1950s to ensure justice for all, discussing how capitalism operated as an economic oppression. He advocated for a people-first economy, creating opportunities to close the gap between poor and rich Americans. He was a well-known supporter of America’s labor movement, arguing that fair wages and workers’ rights served as “economic justice.” In his final speech, given in Memphis on April 3, 1968, in support of a sanitation workers strike, King demanded the city of Memphis “respect the dignity of labor.”

“We overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs,” King said. “But let me say to you tonight that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth.”

King’s work also took root in nonviolence, with many peaceful marches and boycotts. Influenced by other activists such as Mahatma Gandhi and Bayard Rustin, King said nonviolent resistance helped others to see that everyone was part of a common cause for equality. He called nonviolence “a powerful and just weapon, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.”

Though King was assassinated in 1968, his legacy is still prominent in today’s fight for equality. In the same way King modernized DuBois’ message, King’s method of mobilizing through his church networks is now developed into social media outreach. In 2020, many Americans protested after the murder of George Floyd. The Black Lives Matter movement took precedence in 2014 after social media outreach helped plan protests.

“What happened this time with George Floyd is you didn’t have one leader come forward, like you saw before, to kind of push the agenda on city officials and stuff, which led to the Montgomery boycott, right? You had Black people on Twitter, Black Twitter, that were talking about these daily events, the injustice, as if they were in their own living rooms,” Schwendiman said. “They talked about it back and forth, and then people proposed, what are you going to do? Let’s march, and it exploded.”

King’s children are also keeping the fight for equality alive. Bernice King, the eldest daughter of the King family, has asked that on this year’s Martin Luther King Day, activists come together to support the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Voting rights was a critical issue that King advocated for, and the proposed legislation strengthens voting rights for all Americans and limits voter suppression tactics.

“My father would speak and act in a way to ensure that this nation lives up to its promise of democracy by putting pressure on our United States Senate to bypass the filibuster, and instead of taking the King holiday off,” they should make it a day to pass the Voting Rights Act, Bernice King said in a video statement.

Editor’s note: Schwendiman mentioned the ‘community of congruence’, like-minded people who meet to discuss their issues and find they have many things in common. An earlier draft of this story used an incorrect word for that quote.