Gray wolves ordered back onto federal endangered species list, majority of Washington wolves unaffected

A gray wolf pauses on a trail in Pend Oreille County, Wash. (JESSE TINSLEY)

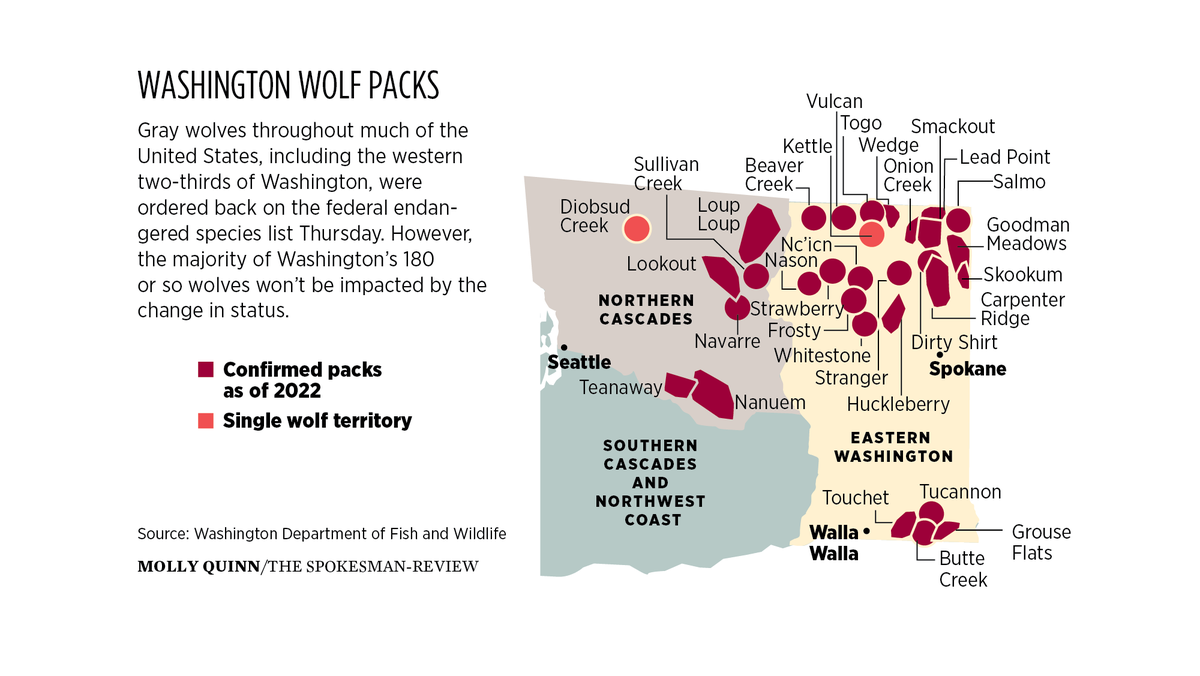

Gray wolves throughout much of the United States, including the western two-thirds of Washington, were ordered back on the federal endangered species list Thursday. However, the majority of Washington’s 180 or so wolves won’t be impacted by the change in status.

A U.S. District judge in California sided with a number of environmental groups that challenged the 2021 removal of wolves from the Endangered Species Act. The judge argued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based its delisting decision off wolf populations in the Northern Rockies and Great Lakes populations, which are more robust than wolf populations elsewhere in the Lower 48.

The relisting excludes the Northern Rockies wolf population, which includes wolves in eastern Washington, eastern Oregon and all of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. The Northern Rockies population was removed from the Endangered Species Act by Congress in 2011.

As of 2020, 23 wolf packs lived in the eastern third of the state; there are six documented wolf packs in the western two-thirds of the state. Not much will change for Washington wolf managers, said WDFW wolf policy lead Julia Smith.

“We’re actually more used to this scenario than we were before,” she said. “WDFW is committed to the recovery of wolves in Washington. That doesn’t change.”

The relisting does mean that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the managing agency for wolves in western Washington. It also means WDFW can’t kill wolves in the western two-thirds of the state.

The department’s lethal removal policy allows killing wolves if they have attacked or killed livestock three times within the last 30 days or four times within 10 months. Two nonlethal deterrents must be deployed before kills can occur. During the 13 months wolves were delisted throughout the state, WDFW didn’t kill any wolves in the western two thirds of Washington.

Wolf advocates praised the decision Thursday while also decrying wolf management actions in Idaho and Montana.

“Wolves are an integral part in the health and resilience of western ecosystems,” Adam Gebauer, the public lands program director at the Spokane-based Lands Council, said in a statement. “Local land managers, state wildlife offices and the federal government must work together and rely on science and not politics to ensure their recovery. Wolves are our allies in the conservation of wildlands.”

In 2021, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game liberalized wolf hunting and trapping rules after the Legislature passed a law calling for a 90% reduction in the state’s wolf population. Montana and Wyoming saw similar legislation. And so far this winter, 23 wolves from Yellowstone National Park packs have been killed after leaving park boundaries, according to the Associated Press. That includes 18 in Montana, three in Wyoming and two in Idaho. That’s the most in a season since the wolves were restored to the U.S. northern Rocky Mountains in 1995 after being widely decimated last century, reports the AP.

“Unfortunately, wolves in the eastern third of Washington remain without federal protections as part of the delisted Northern Rocky Mountains Distinct Population Segment,” said Chris Bachman, an employee of the Kettle Range Conservation Group. “Wolves in the Northern Rockies are being decimated in Idaho and Montana due to new hunting and trapping laws. We need to continue working to restore protections and protect the Northern Rocky Mountain wolves and other carnivores that are vital to ecosystems.”

Mitch Friedman, the executive director of Conservation Northwest, said he thought relisting gray wolves was the right decision although he praised Washington’s wolf management, saying he believes it should be a model for other states.

Meanwhile on Feb. 19, the WDFW commission will be presented with the findings of a study examining the risk of wolves going extinct in Washington in the next 50 years.

The analysis, which hasn’t been published yet, used department data and was conducted by a University of Washington researcher. That report will help inform the state’s periodic status review of the wolf population. The review in turn will determine whether wolves are delisted or downlisted at the state level. Currently, wolves are a state-listed endangered species, a designation that could change regardless of the federal status of Canis lupus. For example: Wolves in Oregon are delisted at the state level and now, after the judge’s ruling, listed federally.

Kim Thorburn, a WDFW commissioner from Spokane, said she was disappointed with the federal ruling. She argues wolves aren’t near extinction, and there are other species facing more dire threats, including sage grouse, butterflies and bees.

“It seems to me that these kinds of decisions pour resources into species that don’t need the kind of help,” she said, adding later, “Wolves have vast amounts (of money) spent on them. Then you look at something like a butterfly or a bumblebee that is so critical to an ecosystem’s survival and it has nothing spent on it.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.