Outdoor writing contest third place: The Alaskan Frontier

“Psshhh!!” A refreshing breeze washes over me, littering my face with salty sea drops and remnants of sea phlegm. A whale had just breached from the ocean depth, and I couldn’t help but feel grateful. At the time, my lifelong friend, Alex, after fishing for a week prior to catch chinook salmon, a luxury no longer shared with those of us who live in Spokane, had brought me to southeast Alaska for a National Geographic exploration. The adventure included boating the inside passages of the Alexander Archipelago while admiring the Alaskan array of natural beauty, untouched by the urban world. The unreal crusade entailed perilous pursuits of the outdoors, including kayaking, hiking and bathing in a mountain pool of clear water. So, when I first felt the splash of the sea’s frigid ice water from a mysterious brute of an animal I had never seen before, I knew I had missed out; the untouched, wild nature of the world is meant for us, and we need to come out of our neo-caves and into the freedom of the unknown.

One of my first adventures was exploring a fjord - a deep inlet of sea between high cliffs, formed by the submergence of a glaciated valley. As we first approached the Dawes Glacier in the Tracy Arm Fjord, I gazed upon a mist-shrouded valley, where the water was a murky dark-blue, and still, without wrinkles or waves. Within stood chunks of unnaturally blue icebergs, just darker than a summer sky, contrasting the gloomy aura of the sea. Nonetheless, the ship’s trudging poisoned the tranquility of the scenery. We were surrounded by fog for a moment before the spectacular, glacially carved cove was revealed. Everyone was silent, stunned by the miraculously calming radiance of the natural splendor. The glacier was ginormous, and from it came countless icebergs. They were comprised of vivid color differences, and I could hear the faint, popcorn-sizzling sound of air bubbles bursting as they melted. As if gigantic cinderblocks dropped from the sky, an iceberg would break off the glacier sporadically and fall into the water below. The blasts were humorously delayed, amplified by the cliffs showing peach-orange and mandarin layers of sedimentary rock. In a dinghy, we boated farther toward the glacier, enjoying the company of my friend and newfound companions, and then returned. On thinning sheets of ice lounged an uncountable multitude of dark-brown harbor seals as blubbery as a fat bus tire, but strangely cute and innocent. As we trekked away, I was anxious for the next thrill of adventure of the wild outdoors.

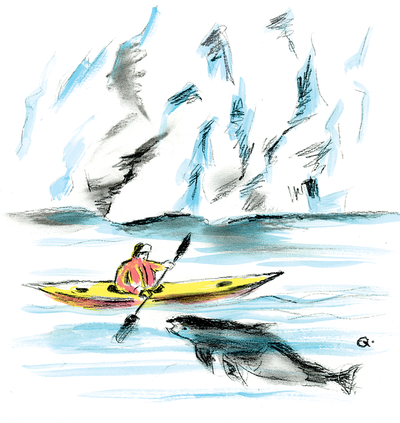

After continuing to explore the Alaskan frontier for a few more days, we came to an island in the Frederick Sound and Chatham Strait where we were allowed to kayak around an island dense with overgrowth and mystery. At this point in the journey, my desire for adventure peaked, giddy with expectation. Here, there were multitudes of islands, surrounded by dark water inhabited by kelp forests, twisted entanglements of sulky rods, bending to the whim of the ocean like black licorice in wet mud. My friend and I endeavored to circumnavigate an island by kayak, toiling our way through the vicious web, while enjoying the marvel spectacle around us. Even so, the Frederick Sound has ingrained itself into my memory for one reason: the Dall’s porpoise. As we were about halfway around the isle, only an arm’s reach from my vessel, an ebony-black, shiny figure emerged from the dark waters, spouting air like a steam engine. It was a gentle creature, yet it imitated one of the scariest: the orca. It made my heart skip a beat because I feared the kayak would tip, suspending me in the arctic water with the unknown beast. But the dolphin-like animal continued to swim elegantly through the intertwining plants. I asked myself, “How could anyone get so close to such an animal?” I was grateful once more, and I wished that everyone could see the marvelousness of the ocean.

My last experience in Alaska was hiking the Inian Islands in the Icy Strait. Our expedition planned to split, me being with the younger group, and hiking a ‘trail’ to a mountain stream. On the trek up, we saw territorial marks scratched onto trees, monstrous scars which oozed a sticky, yellow sap that smelt of forest girth, which must have been carved with angry bear claws. When we reached the top of the mountain brook, I saw a tender drizzle of a waterfall streaming down a miniature, boulder-like cliff into a pool of water. It was an oasis-like basin between mountain rocks and from the mountain bath flowed a gentle brook. It was an explorer’s haven, a place of tranquility, and I was thankful for a third time that I was allowed to experience it. Excitingly, my group and I were allowed to bathe in the water. Though freezing, it refreshed me, and I couldn’t stop smiling seeing Alex and the other members enjoying it as well.

In all, the trip to Alaska was my wondrous encounter with the wild world, which I hope everyone can share to some capacity. Free from worrying about minute details, I enjoyed nature for being nature. However, I know that for those who want a wild experience, Alaska may not be viable. Yet there is an inherent beauty in all the world. A man from Patagonia even said that Spokane is beautiful, though he came from the most iconic examples of natural magnificence. So, ever since my adventure in the Alaskan frontier, I have been exploring the wilderness of Spokane. It renewed a curious, child-like persona within me, and now I enjoy viewing the northwestern terrain. I hope that my story can be a reason for people to also go and explore the wild outdoors, and it doesn’t have to be the Alaskan frontier, just nature, in all its splendor, in your frontier.