Memoir by early Montana game warden highlights dangers, oddities

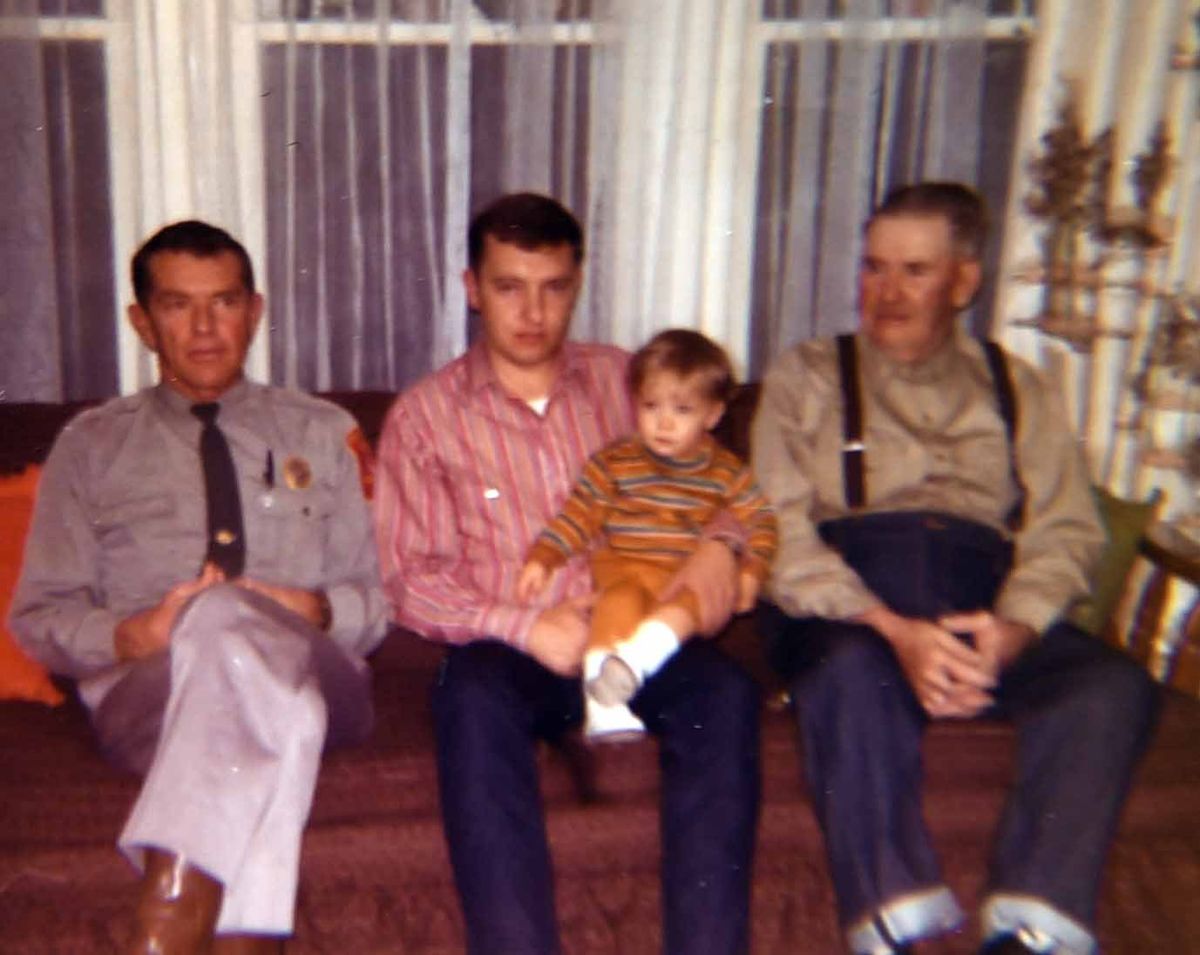

Curtis Tierney credits his love of hunting, the outdoors, shooting sports and collecting to his grandfather, Gene Tierney. He shot this buck where he and his grandfather used to search for arrowheads. (Curtis Tierney/courtesy photo)

BILLINGS – The bullet blasted through the front of the car’s windshield only inches from Gene Tierney’s head, showering his face in shards of glass.

It was a stormy day in November 1957 when the shot was fired from a nearby ridge as Tierney drove up the West Fork of Careless Creek in Montana’s Big Snowy Mountains.

“It didn’t take me many seconds to realize what had happened,” Tierney wrote in his book, “Cry of the Hunted,” published in 1990. “I damned near tore the door handle off getting out, and I drug my rifle along with me. I lay in the mud and snow down by the rear wheel where I could look up the ridge in the direction the shot had been fired from.”

No other shots were fired. Tierney never conclusively identified who had shot at him. A headline in the Great Falls Tribune read, “Game Warden Misses Death.”

Hired on

By 1957, Tierney was a veteran game warden for the Montana Fish and Game Department, now known as the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks. He was hired in April 1944, serving almost 29 years before retiring.

Tierney applied for the job after an injury resulted in his honorable discharge from the Army Air Corps during World War II. After returning to Montana, the idea of continuing his life as a farmer/rancher did not appeal to him, Tierney wrote.

“I recall having moved ten times by the time I was eighteen in addition to being farmed out five or six times to be closer to school.”

With an interest in wildlife and law enforcement, he decided to apply for a warden job.

Family

His memoir recounts details from his work during an early era of wildlife law enforcement in Montana, as well as humorous insights into growing up in a rural state during the Great Depression. With his country upbringing, Gene was good at relating to landowners in the places where he was posted as a warden, which included Helena, Red Lodge, Polson and Harlowton.

“He loved his job,” said Bill Tierney, Gene’s oldest child and a longtime Billings resident. “He loved to be in the outdoors.”

That’s reflected in the foreword, where Gene wrote: “I capitalize Big Game Season because in Montana it symbolizes and commands the same respect as if the words Father’s Day were used.”

Despite his father’s busy schedule, since wardens were expected to be on-call every day all day, Bill said his father taught him how to hunt, shoot and ranch. Some nights, Gene brought Bill along as he sat on a hilltop at night scouring the surrounding land for illegal spotlighting hunters.

“So I got a few night adventures,” Bill said. “I thought it was kind of boring at the time.”

Yet he was “all ears” when Gene and his fellow Fish and Game workers gathered and told stories. Bill also got excused from school on occasion to go with crews as they planted hatchery fish in streams.

Likewise, Bill’s son Curtis learned his outdoor skills and ethics from his grandfather.

“He was a giant in my life,” said Curtis, an art dealer in Bozeman. “We shared a lot of the same interests.”

Those interests included hunting, the shooting sports, a “great passion” for Montana and exploring the state “with a military precision.” Gene was also a collector, filling a small home next to his house along the Musselshell River with his firearms collection, arrowheads and photography. Curtis called it his “big man cave.”

“It was just a dream for any kid,” Curtis said, noting he would spend hours listening to his grandfather talk about items in his collections.

Humor

Gene’s book starts out on a humorous note.

“A couple of old timers told me that instead of being born, I crawled out from under a rock near Shawmut, Montana, on a cold day in October.”

Growing up, Gene recounts a Montana far from being tame. Characters like trapper Rattlesnake Jack, clothed in animal skins, still roamed the countryside, along with bootleggers and plagues of grasshoppers.

“Times were rough and the timid and weak were no longer around” as the Great Depression deepened, he noted. So those who remained had a somewhat ornery sense of humor. One youngster enjoyed putting burrs under saddle blankets. Another would leave carcasses of skinned skunks in mail boxes. Perhaps the worst were two youngsters who starved a feral cat, fed it hamburger laced with cod liver oil and turned it loose in the closed cloak room during a dance at the local schoolhouse.

Bill laughed at the recollection of his father’s acquaintances’ youthful mayhem.

“You just want to put yourself back in that time,” he said.

Gene even had his own run-in with a warden while living in Sweet Grass County. He was walking down a road with a limit of three pheasants on opening morning when the warden pulled up in his vehicle.

“I didn’t brag to him that this was my second trip home that morning with birds,” Gene wrote.

Despite his success with pheasant, Gene wrote that when he was young “deer were nonexistent in the prairie and pine hills country.”

“I was six years old before I saw my first antelope when I was living in what is now known as the heart of the antelope country,” he added.

Challenges

By the time Gene became a warden, game populations had slowly climbed back, thanks in part to enforcement by officers like him, just in time for a new onslaught of hunters and anglers following World War II. Still, he called the bag limits and seasons at that time “haphazard.”

“It did become almost fatal to the (mule deer) as they were practically hunted out in Montana,” Gene wrote. During liberalized seasons, every hunter could kill up to six deer.

His superiors didn’t want wardens to anger the people they were citing, Gene noted. Legislators would routinely have violations dropped for friends. The first biologists hired were secretive and standoffish. At least one sporting club cared nothing for wildlife preservation, the book claims.

Yet Montana was an early adopter of state control over wildlife, with the big game seasons approved in 1872. The first game wardens were appointed in 1889, just two years before the agency was formed. Eight game wardens were initially hired to patrol the vast state. By the end of his career, in addition to enforcing hunting and fishing rules, Gene was also responsible for boating and camping laws, Bill said.

Car troubles

In the early 1950s, the department issued wardens their first state vehicles, nicknamed “Sherman tanks” because of their rough, swaying ride, poor heaters that nearly left the drivers hypothermic in winter and quarter-inch gaps in some panels allowing snow and dust to billow inside. The vehicles were so poorly constructed that it wasn’t unusual for them to literally fall apart going down the road. One warden held his together with seatbelt straps to make it to Helena and trade in the deteriorating hulk.

In one incident Gene recalled, he and a hired hand roped and tied up a mule deer buck that had become too friendly at a ranch home and was feeding on the wife’s garden. As Gene drove down the road to relocate the animal, it broke loose from its bonds and began thrashing around in the back of the rig.

“When the deer realized it was loose and could stand up, he was just like a mad squirrel in a cage,” Gene wrote. “I stopped, got out, slammed the door and stood by watching the buck tear up the inside of the Suburban.”

He couldn’t free the animal until the lasso he had left around the deer’s neck could be cut off through a rolled down window. After the deer was free, Gene inspected the damage to his spare clothing and the Suburban’s upholstery. Despite steam cleaning and repainting the interior of the vehicle, he said the smell of the deer lingered.

Speaking of wildlife and vehicles, Gene writes about working at game check stations and finding bloated animals in trunks almost twice their normal size because they hadn’t been cleaned.

“We have found illegal fish and birds in everything from the hub caps on a vehicle to suitcases looking like a lady’s luggage,” he wrote.

The end

As Gene noted near the end of the book, one thing hasn’t changed for game wardens across all of these years.

“You are exposing yourself to a situation that is not required of any other peace officer in the state. Approximately one half of the people you check for any number of reasons (and half of that you have to write a ticket to) are armed with everything from a .22 caliber pistol to a .300 H&H Magnum rifle.”

Yet the author confessed, after retiring from the force, it left a void in his life that was hard to fill. So he worked as undersheriff in Wheatland County before being forced to resign by poor health. He then took up hand-painting black and white photographs he had taken of the rural countryside.

Bill recalled his father as someone who was multitalented, attributing it to his rural upbringing when folks had to make do with what they had.

Gene even built hydroplane racing boats later in life, along with repairing firearms.

In a 1983 Billings Gazette article, Gene explained to reporter Christene Meyers his reasoning behind the artwork.

“I realized that part of the Old West was rapidly disappearing,” he said.

The painted photographs were one way to preserve an era Gene saw slipping away in Montana, as does his book.

Eugene William Tierney Sr. died on Oct. 2, 1990, at the age of 68.

“I like to think I helped contribute something to the Wildlife Heritage of Montana,” he concluded in “Cry of the Hunted.”

Bill said when he reread his father’s book, it reminded him of a lot of family history he had forgotten.