Walter Cunningham, the last astronaut of Apollo 7, reflects on his time in space as Artemis mission readies

The Apollo 7 prime crew, left to right, are astronauts Donn F. Eisele, command module pilot; Walter M. Schirra Jr., commander; and Walter Cunningham, lunar module pilot. (NASA)

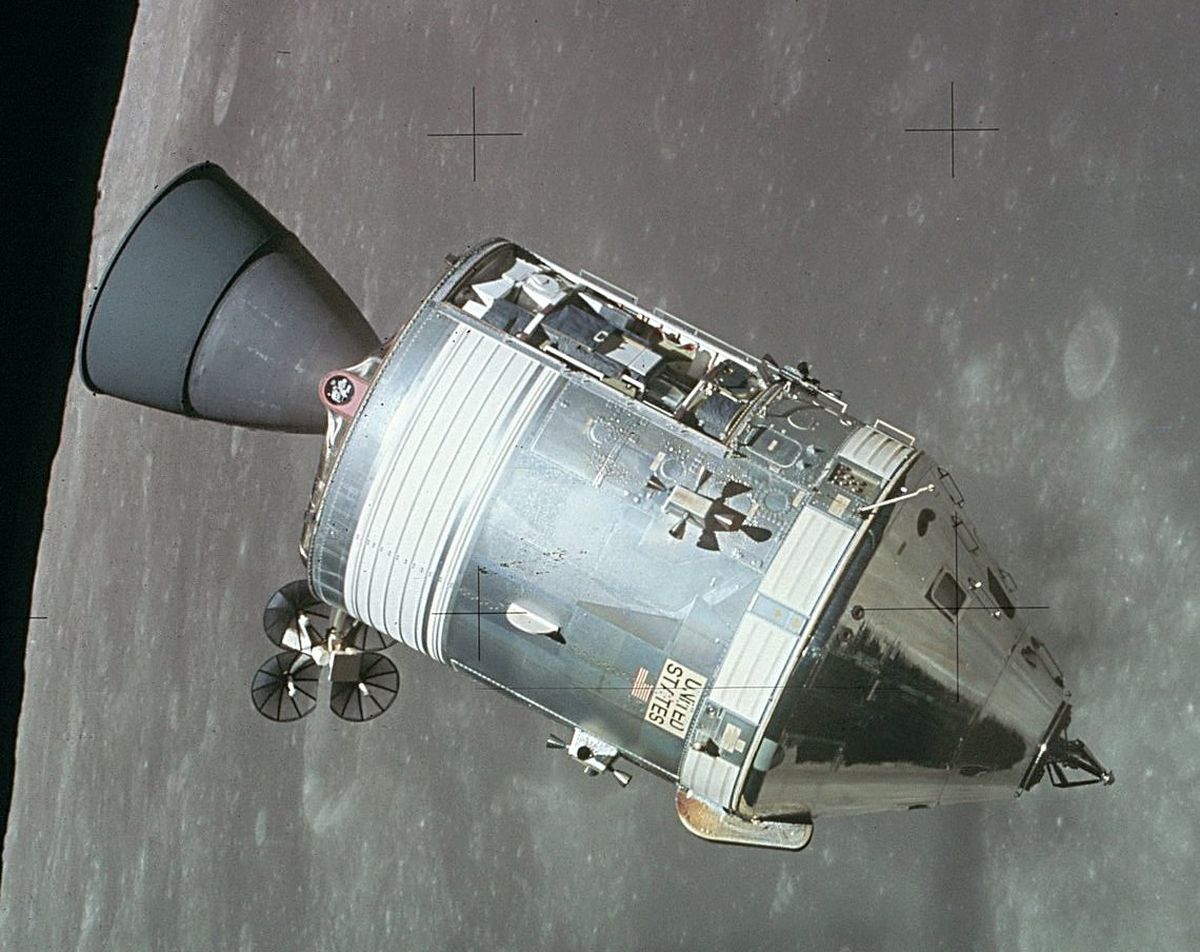

Apollo 7 launched on Oct. 11, 1968, with the goal of demonstrating the capabilities of the command and service module and its crew.

While the command module was designed to get the astronauts from the Earth to the moon and back, the lunar module was meant to land on the moon.

Walter Cunningham, 90, is the last surviving member of the Apollo 7 mission.

“It turns out we didn’t get the lunar module in time,” Cunningham said. “But I was still listed as lunar module pilot. But essentially what was going on is, on board all of us were experts in one way or another on the spacecraft … I was the lunar module pilot, someone else (Don Eisele) was the command module pilot, and (Wally) Schirra was the commander.”

With the success of Apollo 7, NASA was one step closer to the ultimate goal of putting astronauts on the moon. That lofty dream occurred a little less than a year later with Apollo 11.

Don Davis, who worked ground control for Apollo missions 8, 10, 11, 12 and 13, remembers what it was like to land a man on the moon. His job was to develop software for computers at mission control to safely return the astronauts to Earth. After NASA, he help found the Planetary Science Institute, among other projects.

“Oh, well, obviously, it (Apollo 11 moon landing) was extremely, extremely rewarding, and an enormous sense of relief,” Davis said. “Well, an enormous sense of relief once we’d returned them safely to Earth. We still had to get them off the moon and come back. So this was a major step, and I thought it was just a wonderful moment for all of humanity. And the fact that it could be shared with the world via television at that time was very, very powerful.”

Live television broadcasting of an astronaut’s adventure in outer space, however, didn’t start with Apollo 11 – it started with Apollo 7.

Although Apollo 7 never went to the moon, Apollo 7 astronauts had to endure 11 days orbiting Earth. On top of that, Schirra suffered from a head cold, according to Cunningham.

While that may seem more than manageable here on Earth, in space the severity of a cold can be extreme. This is because there is no gravity to pull mucus from the head, which can cause acute discomfort.

Not only was the crew afflicted by illness, but a lot was riding on the success of Apollo 7, which was the resumption of manned space flight since the tragedy of Apollo 1, when three astronauts died when a fire engulfed their command module during routine testing. The astronauts were Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee.

Davis said a lot was resting on the success of the Apollo missions after the disaster.

“I think if we’d had a second major tragedy, then the whole program likely would have been terminated,” Davis said. “But that didn’t happen. And, yeah, we recovered from that tragic fire and learned some lessons from that.

“In hindsight, you always say ‘Well, yes, that should have been avoided in the first place.’… The pressure was on to get to the moon by the end of the decade, and that maybe caused a little more risk than would have been accepted if we didn’t have that particular national goal.”

Cunningham and his crew were originally assigned to Apollo 2, but the failure of Apollo 1 led NASA to believe that more unmanned missions were necessary before they could resume manned missions. When the time came, Cunningham said he was ready.

“It’s kind of funny, if we looked at our attitude back in those days, we didn’t like losing our friends. At the same time, I think we were all impressed and pleased that we were going to be the prime flying, prime crew for that first flight,” Cunningham said.

Ultimately, Apollo 7 ended up a success. Tensions between the ground and those aboard the spacecraft, however, were elevated during the course of the mission. Cunningham said he remembers the good parts of the mission, but also the way his commander, Schirra, made some decisions despite disapproval of ground control.

“But after that (Apollo 7), the media saw the conflict that was going on on board the spacecraft. We never thought about it as bad as the ground did,” Cunningham said. ”From our perspective on board, we felt like we had a hell of a good time.”

Partly because of these elevated tensions, all three members of Apollo 7 never got another space mission.

“I was a bit disappointed. … But there was a brief period of time I was assigned the head of another mission, but then the mission was canceled. And so I never, I didn’t get in line to get another mission,” Cunningham said.

Cunningham is known today as a member of the first three-man crew to go into space, but

he came from humble beginnings.

“We never even knew that there were astronauts when I was growing up. I started off as possibly the poorest person ever,” Cunningham said. “I remember 8 years old when we moved to Los Angeles. I think I was the poorest person in my class … but we didn’t spend our time focusing on that. I was spending my time on what I could do, what I would do and sticking to the mission that was coming up.

“But believe me, it wasn’t space. Flying was still going on. I was in the last squadron that still had a mission from the Second World War. And when we were doing this, I was in high school, and that was going on, and boy, anytime you heard an airplane fly over and the teacher would say, ‘What was that one?’ I’d just turn and tell her right now, I could tell by the sound I knew what was going on. And so that’s kind of what kicked me off. … From day one, I wanted to be the best fighter pilot in any group of people that I was flying with.”

Cunningham earned a college degree while still aiming to be the best fighter pilot in the world.

He joined the Marines after high school and went to Korea. But he soon transferred, pursued his studies and was selected by NASA to become an astronaut.

After his time with NASA, Cunningham became a public speaker, businessman, investor, radio talk show host and even published his own book about his time as an astronaut, “The All-American Boys.”

With the upcoming Artemis mission, which aims to send humans back to the moon for the first time in 50 years, Cunningham is waiting patiently to see what happens next in the world of space exploration.

“I think that humans need to continue expanding and pushing out the levels at which they’re surviving in space,” he said.

“And will that be successful? I don’t know. Because things take time, and we’ll see as it goes on.”