The Tri-Cities are among the fastest growing parts of Washington, according to 2020 Census data. Here’s how they’re dealing with explosive growth

Isidro Ortiz, right, owner of Fiesta Mexican Restaurant, laughs with his wife Elsa and sons Isaac, 11, and Jacob, 10, as they dine at one of their three Fiesta restaurant locations after a church event on Friday, Aug. 19, 2022, in Pasco, Wash. An immigrant from Mexico, Ortiz started the restaurant with his mother and has watched the Tri Cities area grow rapidly since. “This is where I found my opportunity,” Ortiz said. “I felt like the doors were open for me.” More than 50% of the population in Franklin County is Hispanic, and almost 24% of the population in Benton County is Hispanic, according to 2020 Census data. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

TRI-CITIES – Isidro Ortiz opened Fiesta Mexican Restaurant in Pasco with his mother in 2001.

Ortiz, who came to the U.S. from Michoacan, Mexico, when he was younger, wanted to get his mother out of seasonal labor jobs, which are common throughout the agricultural- and manufacturing-heavy Tri-Cities.

Over the past two decades, Ortiz has seen the Tri-Cities grow, and his business with it. Since then, he has opened two more locations in the other two cities that make up the Tri-Cities, Kennewick and Richland.

“This is where I found my opportunity,” Ortiz said. ”I felt like the doors were open for me.”

And he’s not the only one.

Driving through Benton-Franklin counties, construction is practically everywhere. New houses are built and sold within months. Plots of land where development will soon sprout can be seen throughout the hills.

There’s Little Badger Mountain in Richland where just 10 years ago the hillsides were empty. Now, homes along the mountain can be seen from throughout the area. At the new Vista Field in Kennewick, developers are trying to create a more densely populated, walkable area to adapt to growth in a geographically constricted area. At the research district in Benton and the Horn Rapids Industrial Park in Richland, new industrial and manufacturing buildings continue to pop up.

It’s no surprise that the area – known for its agriculture, manufacturing, vineyards and innovation – is developing so rapidly. According to 2020 U.S. Census data, the Tri-Cities has seen the most population growth in the past 10 years in Washington.

Franklin County’s population grew by almost 24%, the largest population change in Washington. Its neighbor Benton County grew by about 18%.

Those are both above the state average. Washington grew by about 14.6%, according to Census data. Spokane County was on par with the state, having grown by 14% in the past 10 years.

“Things have drastically changed in the last few years,” said Erin Braich, transportation planning manager at the Benton-Franklin Council of Governments.

The growth is a mixture of natural increase (the number of births is greater than the number of deaths), low home prices and the pandemic making remote work more easily accessible.

A sprawling upscale housing development is seen from Badger Mountain on Thursday in Richland, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

But there’s only so much space and so many resources for the people who are moving there. As the area continues to grow – and population projections show the growth will continue – the community is looking at ways to accommodate the number of people moving there.

Why people move to the area

Most of the growth in communities in Eastern Washington is because of migration, but the Tri-Cities also heavily relies on a natural increase in population, said Patrick Jones, executive director of the Eastern Washington University Institute for Public Policy and Economic Analysists.

At the same time, Jones said there has been very strong job creation in the area, which has attracted a number of people. Most of the jobs are in technology manufacturing, agriculture or health care. Major employers are the Battelle/Pacific National Laboratory, Lockheed Martin, Bechtel National, Amazon and Tyson Fresh Meats, according to the Tri-City Development Council.

A lot of the growth is driven by jobs in innovation or clean energy, said Michelle Holt, executive director of the Benton-Franklin Council of Governments.

Anecdotally, Holt said she has heard quite a number of people moving into the area from the West Side of the state or Portland. As the pandemic made remote work easier, many people wanted to move to a more rural community, she said.

Despite the massive growth, the landscape in the Tri-Cities changes quickly from housing to agriculture.

Some people were priced out of the homes on the West Side and moved to the area for cheaper housing or cheaper utilities, like electricity, Holt said.

Growth in Hispanic populationMuch of the growth in the area would not have happened without the growth of the Hispanic population.

More than 50% of the population in Franklin County is Hispanic, and almost 24% of the population in Benton County is Hispanic, according to 2020 Census data.

“Were it not for the influx of Latino folks and increase in Latino population … this place would not be where it is,” said Martin Valadez, interim executive director at the Tri-Cities Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

The people who move in then get jobs, buy houses, open businesses and contribute to the local economy, he said.

Carlos Martinez, CEO of Dura-Shine commercial cleaning service, originally opened his business in Othello, but once he realized how many people were moving to the Tri-Cities, he relocated.

“We’re in the cleaning business, so we want buildings,” he said. “We thought, ‘The growth is happening in the Tri-Cities. That’s where we need to be.’”

He moved his business in 2004. At the time it was just a small office, but by 2013, he built a large office in Pasco, and his client base continued to grow.

About 75% of his staff is Hispanic, Martinez said. Most came to the Tri-Cities from Mexico, California or Texas.

Martinez said one of the reasons why the area attracts so many Hispanic people is because there’s work. Most people who are coming here are looking for entry-level positions, like farm work, service work or processing and manufacturing.

Most are of Mexican origin and are attracted to the agricultural and manufacturing work in the area, Valadez said.

While agricultural and manufacturing is still a large sector of the workforce, Valadez said the type of work is starting to change, with even more people going to work in school districts, the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory or the Hanford nuclear site.

“We’re starting to diversify a little bit more professionally as more people get high school degrees and then on to college,” he said.

A lot of the Latino population move in from other parts of the state, he said. When people who grew up in smaller towns like Othello or Mattawa go off to college, many will end up moving to the Tri-Cities afterward for more professional opportunities, lower home prices or the number of amenities, he said.

What’s neededOne concern everyone has as more people move into the Tri-Cities: housing.

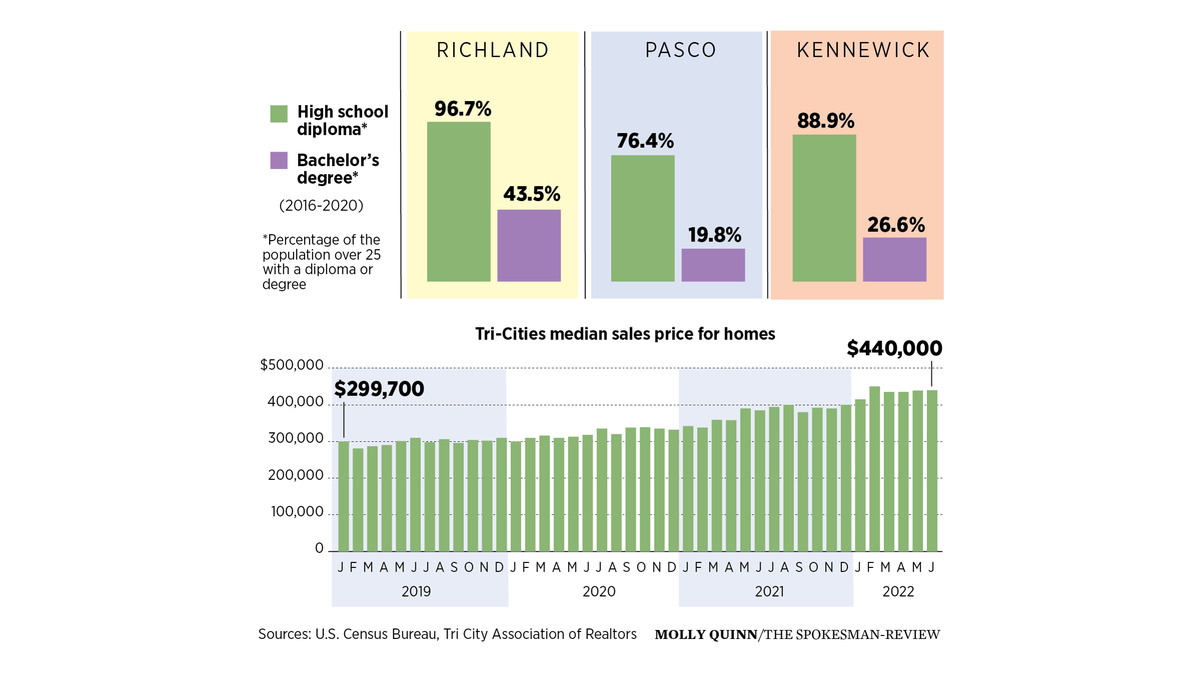

Housing prices have soared recently as availability becomes scarce. As of June, the median house sold for $440,000, according to the Tri-City Association of Realtors. A year prior, the average house sold for $385,000. Before the pandemic, in 2019, it was $309,500.

The soaring home prices are similar to what’s been seen in Spokane, where the median sales price for a home was $440,000 in June. That’s compared to $380,500 a year ago. Before the pandemic, in June 2019, it was $265,312, according to the Spokane Association of Realtors.

Valadez said when he moved to the Tri-Cities, he used to tell people that even a farmworker could own a house.

“And that’s not the case anymore,” he said.

Wages have increased some, but the rate at which housing prices have increased is “insane,” he said. Young professionals from the area are competing with people moving in from outside the area, Valadez said.

“I can’t believe how housing prices have shifted,” Braich said.

Although new developments seem to pop up every day, houses sell within days, he said. As growth continues, utilities, emergency services and schools have all had to adjust.

New middle and elementary schools are opening. New fire and police stations are being built closer to new development, like the new Vista Field in Kennewick. Water system suppliers are expanding as officials anticipate a need for more landscaper products or septic products.

And like everywhere else, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a huge impact on the economy in the Tri-Cities.

Many Latino business owners took a “huge hit” during COVID, Valadez said, and many still are trying to recover, especially with inflation and a growing labor shortage.

During the pandemic, Martinez said his cleaning service had to turn down clients because they didn’t have enough staff. It was the first time in 27 years that they had to turn away business, he said.

With a growing Latino population, Valadez said there also is a need for additional resources for the community, such as language services or access to information on housing, evictions, business grants or vaccine distribution.

The Latino population has increased rapidly in the past 20 years, so it doesn’t have a long history in the area with such a large population. Between 2010 and 2020, the Hispanic population in Franklin County grew by more than 31%. In Benton County, it grew by almost 51%.

“I think there’s still work to be done,” he said.

The Hispanic Chamber of Commerce tries to be a trusted messenger for the community, Valadez said. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, for example, they often worked with the Department of Health to provide information about the virus and held vaccination clinics.

Learning to accommodate growth

Sharon Grant remembers seeing the first “No Trespassing” and “Private Property” signs on Badger Mountain almost 20 years ago.

Grant, an avid hiker, spent a lot of time hiking the trails up and down the mountain, and when she saw the first signs of encroaching development, she knew she had to do something.

She got a group of local residents together and helped formed Friends of Badger Mountain in 2003. The group wanted to do something before the trails they always used were taken over by development, she said.

Within a year and a half of forming, the group raised money and purchased 574 acres on the mountain. It’s now owned by the county as the Badger Mountain Centennial Preserve, which has more than 8 miles of trails.

“If we hadn’t got in there when we did and weren’t as successful as we were in raising money, that land would have been lost,” Grand said. “That land would be development.”

But they didn’t stop there. They eventually added more land to the preserve and looked to other mountains in the ridge. In 2016, the group acquired 195 acres on Candy Mountain in Richland. It’s also looking at creating trails on Red Mountain, where many of the local vineyards are located.

Though they are still working on building a trail through the area, one place where they haven’t been as successful is Little Badger Mountain, which now has hundreds of houses and even more planned.

“The development is very intense,” she said.

Most future trails likely will have to be created through residential areas, Grant said.

In some places, like Candy Mountain, there are new houses right up against the preserved land, Grant said.

“I don’t know how we’re going to preserve more land,” Grant said. “It is going to be challenging.”

Developers in the area are trying to be creative about how they move forward. One example in Kennewick is Vista Field.

The development will be built on an old airport strip but will become a walkable, urban space – the first of its kind in the region, said Larry Peterson, director of planning and development at the Port of Kennewick.

The hope is that it will become a new regional town center that focuses less on cars and single-family zoning and more on mixed use, Peterson said.

The site has green spaces, waterways and walking paths throughout.

“The intent is building an interesting place,” Peterson said. “It’s more about how much stuff we can get on a piece of property versus sprawling.”

The Port of Kennewick began receiving proposals for the first 20 acres of land in early July.

The site won’t accommodate all of the people moving into the area, Peterson said.

It won’t necessarily change the game, but the goal is to add some housing stock while at the same time build a community that’s never been seen before in the area.

More development on one piece of land is a trend that is coming, Peterson said. It makes economic sense, and Vista Field can be a local example that people can point to for that type of development.

“We aren’t going to solve the housing crisis,” Peterson said. “What we are hoping is some ideas can be decanted from this.”