Heat pumps: Coming to a home near you? Washington building code proposal prompts debate as Inflation Reduction Act could spur their use

Karl Johnson’s heat pump is photographed on July 15 at his home in Spokane. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Karl Johnson was just looking for a way to keep his Corbin Park home, built in the early 20th century, comfortable.

The gas-fed furnace was on its way out, and hi s central air conditioner had already failed. To cool the home, Johnson had several portable units running throughout the day in the summer, belching hot air back into the rooms and driving up his energy bill each month.

“At some point, it’s just insanity to keep up with trying to address the issue,” Johnson said.

So he started researching central air systems online and settled on a heat pump for his home – a combination heating and cooling, electrified system that policymakers and the White House have been pushing as a method to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Democrats’ Inflation Reduction Act, which passed the Senate by a razor-thin 51-50 vote on Sunday, includes a major boost for climate-friendly energy systems, including heat pumps.

The bill includes rebates and incentives for the purchase of heat pumps for both air and water conditioning in residential structures. The legislation would provide rebates of up to $8,000 to install heat pumps in homes for the next decade, according to Bloomberg. Those who wouldn’t qualify for the rebate could still get tax credits of up to $2,000.

The inflation act also piggybacks on a decision made by President Joe Biden in June to use the Defense Production Act to spur domestic production of appliances that help curb carbon emissions, including heat pumps, by providing $500 million in that effort, according to The Hill.

Johnson paid about $6,000 for the Lennox brand pump that he demonstrated on a recent Friday morning.

Cranking the thermostat down to 66 to demonstrate the fan on his smartphone, Johnson said his device has worked like a dream.

“When you reach your hand behind our couch, where two vents are, it’s actually cold,” he said. “Sometimes we have to put blankets on.”

The Washington State Building Codes Council – after pushing to make heat pump installation mandatory in new commercial construction – has before it a proposal to require the same in new homes built in 2023 and beyond, with some exceptions. The panel took a vote at the end of June forwarding the proposal to a public hearing that will take place later this fall.

Any revisions to the code, including the requirement for residential electric heating, would need to be approved by Dec. 1 in order to take effect next year.

Proponents point to studies indicating such a move, even with backup systems that provide heat through traditional gas when temperatures plunge in the winter, could lead to a home in Spokane County that produces at least 60% fewer greenhouse gas emissions annually over the next decade. But those savings may come at the cost of an immediate increased strain on the energy grid and potential rate hikes to pay for increased transmission and production of electricity, not to mention maintenance of gas transmission lines that a home may not even use after making the switch.

“When I talk with employees and policymakers about these issues, what I like to remind them of is we need to be thinking about unintended consequences,” said Jason Thackston, senior vice president of energy resources and environmental compliance officer at Avista Corp., in a recent interview.

Thackston said the utility anticipates that, if all the natural gas customers in its service area were required to switch to electrical heating in the winter, utility rates would need to double to pay for new infrastructure and production facilities to meet the demand when the thermometer dips in the Inland Northwest.

Of course, the conversion won’t happen that way. It will begin with contractors building new homes that use primary electric heat, and continue with people like Johnson adopting the technology in existing dwellings. That’s the point of incremental environmental change, said Brian Henning, the director of the Gonzaga Center for Climate, Society and the Environment.

“We’re in a deep climate hole,” Henning said. “The first step is to stop digging.”

The need for a backup

The idea of a heat pump isn’t new.

In fact, such devices were tested by the Washington Water Power Co., which became Avista, in the 1950s when most homes in the region were heated by oil. The early returns, based on studies at the homes of employees in Spokane, Pullman, Clarkston, Coeur d’Alene and Lewiston, showed a potential cost-savings of 25% to 35% over oil, according to an April 15, 1955, article in The Spokesman-Review.

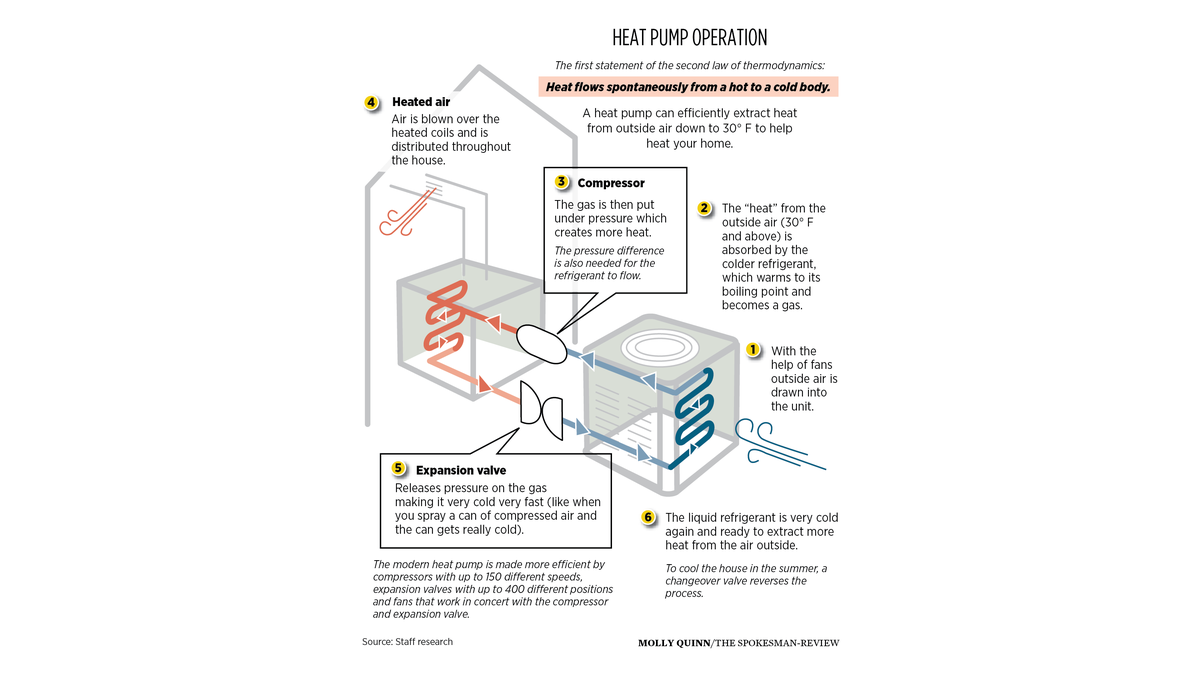

A traditional air-to-air pump works exactly like an air conditioner, but in reverse. A reversing valve in the machine turns the outdoor device into an evaporator in the winter, spitting cold air out while drawing heat from the outdoor air to warm the inside of the home.

This causes a problem that is exacerbated in colder climates. If the temperatures dip to the near-zero levels often seen east of the Cascades in the winter, ice can form on the outdoor evaporator. To melt that ice, the machine reverses its function once again, basically becoming an air conditioner at a time when the air outside is at its coldest.

The solution has been, and continues to be, resolved by introducing an auxiliary power source. Often that’s either an electric coil inside the heat pump or a traditional, gas-burning furnace, to heat the air inside the home while the outside device deices.

Johnson’s pump has a backup, gas-burning furnace that cost more to install than the pump itself. Just like his temperature, he can control on his smartphone at what temperature the backup natural gas will kick on.

The new codes under consideration by state officials would permit supplemental heating under certain conditions, and allow replacement of existing nonelectric heating systems so long as the rated capacity is the same or less.

Johnson’s heat pump was installed by NORCO Heating and Air Conditioning. Len Pedersen, owner of the company, said he’s still advising home owners to install backup gas systems because of both the cost and the demand of an electric furnace, which will run more frequently in areas of the state that get colder than others – specifically, east of the Cascades.

“As soon as we get down to 10 degrees, and you kick on the electric backup furnace, that’s like having six to 10 air conditioners going on outside,” Johnson said.

Spokane County Commissioner Al French, who serves on the State Building Codes Council and has pushed against the electric requirements, noted such a change also would require increasing the electrical capacity at a home or multifamily building. The additional costs would be passed on to renters, he said, and leave them without a source of heat should the power fail in the winter.

The requirement would most directly hit low-income renters and people of color, French argued, increasing their costs of living.

French said the effort to change the building code to require electricity circumvented the Legislature, which refused to forward to a vote a bill this session that would have prohibited expansion of new natural gas services in the state.

“The governor is trying to go around that,” French said.

There’s no cost-savings in putting in a heat pump and furnace system compared to a traditional furnace and air conditioner setup either, Johnson said.

Supporters of the proposal, however, argue that any cost analysis should include the social costs of continuing to burn gas and send greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The problem isn’t so much economical as it is existential, they argue, and the data does show that, over time, the switch will undoubtedly benefit the environment.

Cutting greenhouse gases

During the pandemic, Theresa Pistochini watched as her local utility company tore out and replaced underground gas lines throughout her neighborhood.

“I wanted to say, ‘Can you not do this?’ ” said Pistochini, co-director of engineering at the Energy Efficiency Institute at the University of California, Davis. “I had no say in it.”

Pistochini has personally moved away from natural gas at the same time her professional work has demonstrated that changing from a traditional furnace to a heat-pump system will reduce greenhouse gases.

In April, the journal Energy Policy published a peer-reviewed article from Pistochini and others at the institute that quantified how much in emissions a household could expect to reduce with a heat pump.

The study took a specific house’s energy consumption needs and modeled the emissions reduction based on the climate of six different regions in the United States. The reductions were most modest in the Midwest, where extreme cold winter temperatures would require the more frequent use of an auxiliary energy source. They were highest in the Pacific Northwest and the Northeast, and in Spokane the estimation was a reduction of 62% to 68%.

Those calculations over a 15-year period are based upon utilities, such as Avista, reducing their carbon footprint. The utility has stated its intention to reduce emissions by 30% by 2030 and provide 100% clean energy by 2045, in addition to no longer funding improvements at the coal-fired power plant in Colstrip, Montana, beginning in 2025.

Earlier this summer, state regulators approved the utility’s most recent Clean Energy Implementation Plan.

Thackston, of Avista, said that the increased demand on the electrical grid could force the utility to pursue other methods of production in the interim, including possible natural gas-burning plants that would undermine efforts to reduce emissions.

“We think about the energy ecosystem as a whole ecosystem,” Thackston said. “We are interested in advocating for the right fuel in the right application, and giving our customers choice.”

Serving homes with electricity produced at natural gas-fired plants is also less efficient than permitting individual homeowners to continue burning gas in their furnaces, Thackston added.

The utility digging up the replacement lines represents another problem as more homes move to electrify heating: the maze of natural gas pipelines that eventually will need to be replaced or repaired. Fewer people using and paying for natural gas service could lead to a shift, Pistochini said.

“That’s going to drive up the cost, as natural gas consumption drops,” she said. “Who’s going to pay for all that infrastructure? That’s very confusing.”

Henning acknowledged that in the short term, utilities may need to rely on natural gas to meet the increased need for electricity on the grid. But state laws will push them to other sources of energy in the long term, which is reflected in Pistochini’s findings of future greenhouse gas reductions.

Pushing the requirement for new construction also will be less disruptive and give utilities time to build out the grid and develop better storage capabilities, Henning said.

“The more we can do these things incrementally over time, the less expensive it’s going to be,” he said.

‘It makes sense why they’re starting there’

While heat pumps used in the home typically take their warmth from the air outside, there are examples of other types of nonnatural gas heating in town if you know where to look.

“We’ve seen the writing on the wall, even before this building code came out,” said John Gillette, district director of facilities for the Community Colleges of Spokane.

That’s why the main hall at the Spokane Community College campus on Mission Avenue uses water pumped from the Spokane aquifer to cool the building in the summer.

The water deep below the earth is pumped up at 54 degrees, enough to cool the air when it’s hot.

Those types of geothermal systems also have been around for decades. Their new application indicates a shift in the way the community is thinking about air heating and cooling, said Anthony Schoen, a mechanical systems principal at the firm MW Engineers in Spokane. The firm designed a similar system at Gonzaga University’s John J. Hemmingson Center built in 2015.

Schoen likens the shift to ones already seen in Spokane, when the Washington Water Power Co. (now Avista) stopped running its steam heating to clients in the 1980s, and the large twin smokestacks over the downtown skyline became beacons for beer and business rather than energy production. Or when those coal chutes seen in the basements of homes built in the early 20th century were boarded up and replaced by oil and then natural gas systems.

“This isn’t the first time there’s been an energy shift,” Schoen said.

New heat pump technology has improved since the 1990s and 2000s, Schoen said, leading to products that can increase efficiency and lower utility costs in homes to less than half of what some users are paying for gas heating and approach equivalent gas heating costs for commercial facilities.

The electric utility cost of using a heat pump is dependent on the system’s efficiency. Depending on design and the selection of equipment, utility costs could be higher using electric heating because of the low cost of natural gas in the Inland Northwest, or as low as half of the equivalent gas cost with higher-efficiency equipment, Schoen said.

“There will be a learning curve for building owners and building operators,” Schoen said.

But he acknowledged that the move would not be easy, especially in the short term.

“It’s going to be difficult, and challenging, at least initially, to provide reliable heat-pump heating solutions in our climate while minimizing backup electric heating that has a much higher draw on the power grid,” Schoen said.

Still other engineers, builders and policymakers have argued to the building codes council that the move is being made too quickly, without the additional power through renewable energy sources and without the infrastructure in place to meet the new electrical demand.

“It’s within a year from now,” Thackston said. “That pace is not a pace we’re comfortable with.”

Henning said requiring the technology in new construction is an appropriate method to continue steps forward in reducing gasses and promoting greener technology, ensuring that anything that’s built new can one day be on a power grid that is carbon-neutral and moving away from continued emissions from individual homes.

“It makes a lot of sense why they’re starting there,” Henning said.

Johnson, the Corbin Park homeowner, said he’s been pleased with his heat pump so far. His energy bill in June was about 60% lower than last year, when he was using the portable conditioners and a heat dome settled over the area, sending high temperatures soaring.

Johnson knows the real test will come when winter arrives, and how well his heat pump will do on those cold February nights.

“I think there’s probably some expectations that need to be realigned,” he said. “I also hadn’t received any cautionary tales while they were installing it.”