A Connecticut lawyer has gotten 522 years taken off prison sentences. He’s not done

HARTFORD, Conn. — There aren’t a lot of attorneys who are making it their mission to get inmates out of prison before they’ve served out their sentences.

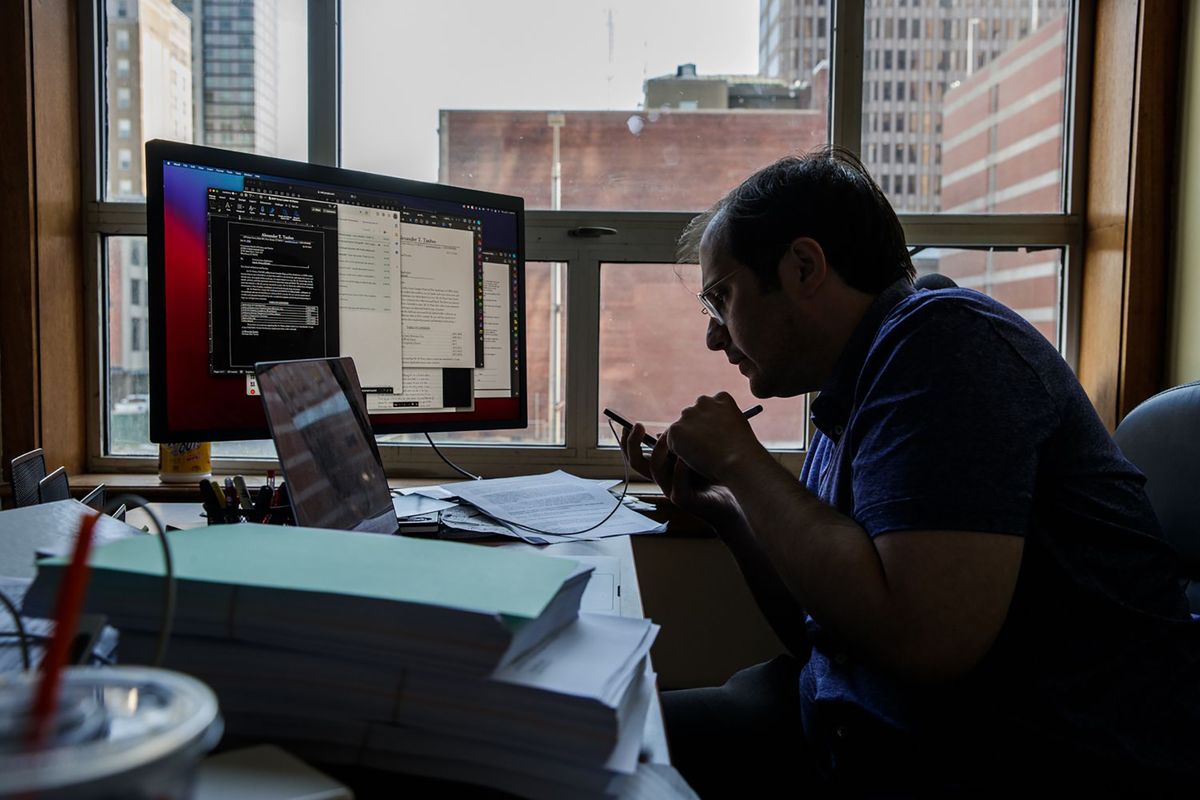

Alex Taubes, just seven years out of Yale Law School, has found a niche that is yielding results. As the result of recent Supreme Court decisions and changes in state law, he has been able to have time taken off his clients’ sentences, helping them become effective members of society.

The total so far: 522 years taken off the sentences of 48 men and three women in the past two years, most of them felons who were given extraordinarily long terms when they were young.

Two of them now work for Taubes as his legal assistants. One, Michael Braham, earned two degrees while serving time for murder.

“I was in 24 years on a 32-year sentence. And, throughout that whole time I was battling for post-conviction relief,” said Braham, 47, whether it was sentence modification, which would reduce his time, or commutation, which would get him out on parole.

At age 21, “I was charged and eventually convicted of murder.” He took a plea to avoid trial.

“It wasn’t a murder. It was manslaughter, but the state insisted on murder,” Braham said, which if he had been convicted at trial would have brought him a 60-year sentence, the standard at the time.

“That’s what kept me going through all those years was my post-conviction work, which I gave up on that one time and then I bumped into someone and he kind of told me how foolish that was. So I filed something that took me another 10-15 years to litigate unsuccessfully, not because I didn’t have merit but just because that was the times, right? Lock him up and throw away the key.”

A friend in prison dubbed him “the paralegal.” His goal now: to become a lawyer.

He filed another appeal to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which he said was rejected without the board apparently having read it. “It came back pristine,” he said.

Meanwhile, Braham said, “I got a bachelor’s from Wesleyan majoring in philosophy. I got a bachelor’s from Charter Oak State College. That’s a blended concentration of philosophy and law.”

Then he met Taubes.

Matthew Abraham, 39, the other member of Taubes’ staff in the cramped office on Elm Street in New Haven, was arrested at 18, charged with murder, convicted at trial and sentenced on a charge of a manslaughter with a firearm.

“The first couple of years of my prison sentence was kind of rough,” he said. “My adolescence. I was still shaking off some stuff that I was carrying with me, a lot of trauma and all that — not even shaking it off, not knowing how to deal with it.”

But Abraham’s grandmother, Mattie McFadden, who died in June 2021, gave him tough love.

“She just told me she would never send me money for commissary,” Abraham said. “She said the only thing I will pay for you to do is to go to school, because that’s all she ever wanted for me was to go to school. So she did that.”

So Abraham began studying law in the prison library, finally getting a job in the law library at Cheshire Correctional Institution. He filed cases, representing himself, but kept getting denied.

“And then I just kept digging and digging for cases and ultimately I found a case I believe from the ′70s where something was wrong,” he said. “And I didn’t actually think that that was going to be the thing that was going to get me released. I put it in as a footnote. Just like, if the court wanted to consider this, you can just look at that.”

That turned out to be the key.

“Thankfully I did that, because that’s what ultimately got my sentence reduced. The first time I got it reduced. So I won the appeal,” and the judge took off three years, he said.

“I was sentenced to 40 years suspended after 30 years and then they ended up just taking off three years,” Abraham said, finally serving 20 years, seven months.

He also studied at Wesleyan, where he was referred to Taubes. “He told me at no charge he will take me to the sentence modification,” Abraham said. “That’s what he did. He kept his promise. He kept his word, and he ended up putting in a modification.”

At the hearing, the victim’s mother, who had opposed Abraham’s release, tried to get the judge’s attention. “She interrupted and I believe it was Alex that was like, Your Honor, I believe she has something to say. And he pointed out that she was trying to get the court’s attention, and she told the court to let me out, to let me free. She said she heard everything that I’ve done and accomplished while I was in prison and she thought I will be good for the community. She pretty much begged the court to let me free. It was pretty powerful and emotional.”

He was released five days later. “And now here I am, working for Alex Taubes,” he said.

“So now I’ve been here and there’s many people that I know that Alex has gotten out of prison. I mean, guys that I’ve been in prison with for 20 years. And now they’re free.”

‘What I want to see’

Abraham said of Taubes, “a lot of times he didn’t even take people’s money.

“He just wanted to help people, and he has been doing that. He’s been helping people. … I talked to a lot of guys inside. I’m still in contact, close contact with a lot of folks. And they all tell us, they all hire Alex because they know how good he is.”

While those who are tough on crime might question why Taubes focuses on getting convicts out of prison, he has a ready answer.

“The notion that a person who’s sentenced needs to serve 100% of the time that the judge gives at the sentencing is actually a pretty new one that came about during the tough-on-crime 1990s and what were called truth-in-sentencing laws,” he said.

He said a life sentence in Connecticut was defined as 20 years and then 60 years. “And then it used to be that a prisoner could earn up to 17 days off of their sentence each month for good behavior and working a job,” he said. That too was abolished in 1994.

“And now someone like Matt or Mike, who’s in prison for 20 years getting college degrees, helping their communities, mentoring young men, they’re not getting any credit at all for the good work and good behavior they do in prison,” he said. “And there’s a real problem with that.”

Taubes said it denies prisoners hope.

“If you don’t give them any reward for doing good and becoming better … what are you going to do to someone when you’ve already told them, ‘I’m putting you in prison for the rest of your life and there’s nothing you could ever do to get out of that’?” he said.

“And what we’re seeing right now, in our communities with young people, and the violence and the crime that we’re seeing. A lot of it is a repeat of history.

“And if we had some of these people who have life experiences out here to teach some of the lessons that they’ve learned that allowed them to transform their lives completely, I really believe that could be the catalyst or turning point or a tipping point to starting to really tackle the problems of the violence that we see in the city and trying to make the city a more peaceful, healing place for all of our children to grow up,” he said. “And that’s what I want to see.”

Taubes said the science of brain development also argues for keeping young people out of prison. “The science now shows us that a young person who’s 20, 25 years old can really change and become a whole different person,” he said.

But Taubes sees a need to change the laws to “automatically take a look at some of these people who have been sitting in jail for so long, and assign someone to work with them to look at whether or not the sentence that was imposed decades ago is still serving the needs of the people of the state of Connecticut here today.”

Taubes, 33, began his career working with attorney David Rosen on the class-action lawsuit that won a settlement for more than 1,000 residents of Church Street South, the low-income residential housing complex across from New Haven’s Union Station. It’s since been razed.

He also worked with ACLU of Connecticut on the case in which the group argued that prisoners should be released during the pandemic because of the lack of social distancing. “The settlement did some good things, but it didn’t provide for anyone to be released from prison,” Taubes said.

“And obviously, a lot of the guys I was working with, that’s the reason they were working on the case is because they were hoping they could get out through the case. And some of them had a really good point.”

Taubes worked to get Braham out, then two things changed “that really changed this practice and made it take off,” Taubes said. “One was that the legislature passed a bill that for people who went to trial like Matt, you no longer had to ask the prosecutor for permission to take your case in front of a judge. They just filed a motion in court and got a court date.

“And then the other thing that happened was the Board of Pardons and Paroles released a new policy where they would be starting to exercise the power of commutation of sentences again after a three-year hiatus, where they had not been even considering applications for commutation.”

Also, the Supreme Court ruled that anyone under age 18 given long sentences, even if ineligible for parole, “is entitled to reconsideration of that sentence,” according to Michael Lawlor, a professor at the University of New Haven and former criminal justice adviser to Gov. Dannel Malloy.

“And so the first one of those was the Michael Cox case, where we got 30 years off of his 75-year sentence, and then the board acted even further and letting him out because of his dialysis and the medical conditions and things like that,” Taubes said.

“And since that one we did with Michael Cox, I think our 10 biggest victories in the last two years have come through the parole board as opposed to through these motions in court.” He’s working on another round of motions.

Taubes has also tried politics, running a losing campaign in 2014 against then-state Rep. Noreen Kokoruda, R-Madison, when he was in law school. He grew up in Madison. He also ran against state Senate President Pro Tempore Martin Looney, D-New Haven, in 2020, but didn’t gain enough signatures to get on the primary ballot.

“And as part of that, we brought a lawsuit against the state, because during the COVID-19 shutdown, how is someone supposed to go door to door to get petition signatures to qualify for the ballot?” Taubes said. “So we sued saying that the petition requirements in Connecticut were unconstitutional because of COVID. And three days after we filed our lawsuit, Gov. [Ned] Lamont changed the rules, allowed electronic signatures, reduced the number of signatures, gave more time to comply.”

Taubes lost his case but is appealing. He’s also representing a candidate who is challenging U.S. Rep. John Larson, D-1, in which Lamont’s accommodations no longer apply.

“And they came just short,” he said. “And what we did when we brought this lawsuit was we found out that Connecticut is not only the most strict state in the country when it comes to running for office and qualifying for the ballot, but that no one has ever made the ballot in a primary against an incumbent U.S. House member in Connecticut, and Connecticut is the only state in the whole country where that’s true.”

Taubes said the state laws “to get on the ballot to run for office to improve your community stop people from being able to do that, and that’s bad for everything we want in our government. We want more efficient government. We want more engagement. We want more justice. But the people in power stop us from being able to participate.”

So, while his practice is mainly about getting people out of prison as a civil rights lawyer, “my goal is to make sure that the government protects people’s constitutional rights, and that our democracy is a healthy place where people can succeed and have opportunities and live their lives.”

———