Viola Davis reveals the trauma that shaped her as an actress

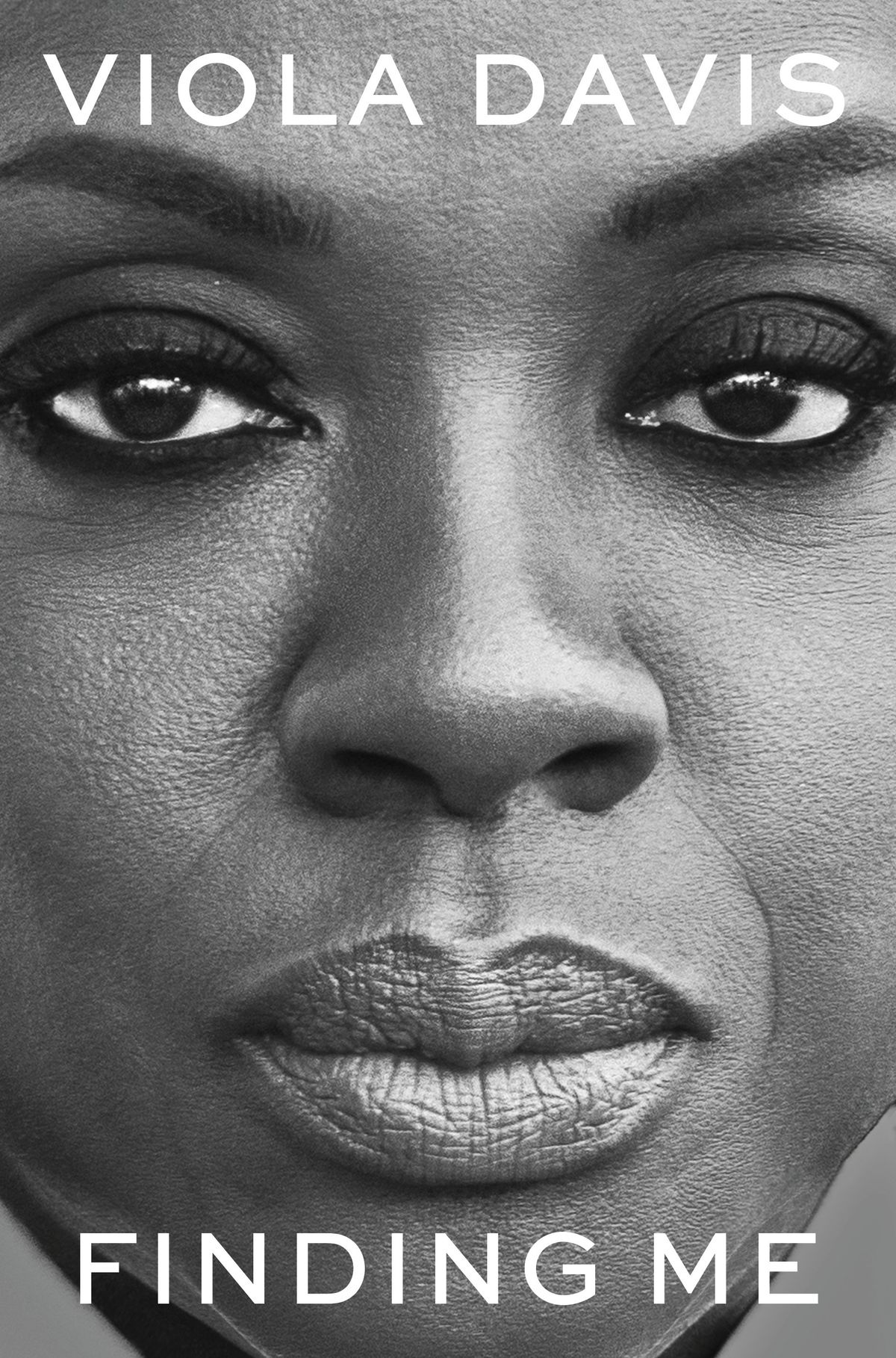

“Finding Me” by Viola Davis (HarperOne)

Actress Viola Davis opens “Finding Me” with a double dose of profanity, an announcement that her memoir will be no breezy Hollywood tell-all. Instead, she plunges into her childhood trauma – and doesn’t depart those depths for some time. The ensuing introspection gets to the bottom of Davis’s deep-seated pain and how it shaped one of the finest actresses of a generation. When the Oscar, Emmy and Tony winner does drop Will Smith’s name in the opening pages, to set up a heart-to-heart they shared about their respective upbringings, it’s one of the few references to her stardom before the final chapters.

Davis is more interested in framing her decorated career within the racism, generational abuse and sexual assault she overcame while growing up “po” – “That’s a level lower than poor,” she clarifies – in Central Falls, R.I. Her memories of the bigoted grade-school bullying she endured are upsetting. So are the descriptions of her dilapidated homes, including one rat-infested apartment she bluntly refers to as a “death trap.” Pet lovers may have a tough time enduring detailed descriptions of cruelty to animals that Davis recalls witnessing. In a harrowing revelation, she says her brother sexually abused her and her sisters when they were young.

But Davis largely focuses on the volatile relationship between her empathetic mother and her violent, alcoholic father. With brutal candidness, she channels the unrelenting terror of living in a household of domestic abuse: “There are not enough pages to mention the fights, the constantly being awakened in the middle of the night or coming home after school to my dad’s rages and praying he wouldn’t lose so much control that he would kill my mom.” Eventually, though, there comes her father’s transformation into a gentler soul and loving partner. Later, her recollection of his death is devastating. With fine brushstrokes, she paints a complicated portrait of a complicated man.

Davis acknowledges that she eventually became an actress as a coping mechanism of sorts. “The process and artistry of piecing together a human being completely different from you was the equivalent of being otherworldly,” she explains. “It also has the power to heal the broken. All that was inside me that I couldn’t work out in my life, I could channel it all in my work, and no one would be the wiser.” If you know Davis’ work, then you understand the wrenching results of mining her emotions.

When Davis remembers her early struggles as an actress – working as a day laborer and telemarketer to make ends meet, facing various ailments without health insurance – her professional fortitude becomes all the more admirable. And that goes without mentioning the racism, sexism and colorism Davis has long navigated in the industry. She writes that Juilliard and its white-centric worldview suffocated her artistic instincts before an eye-opening trip to the Gambia helped her rediscover her voice. She also cites the roadblocks she navigated because of her weight and skin tone, noting that “almost every role I auditioned for were drug-addicted mothers.” It’s infuriating and sadly unsurprising.

Although Davis isn’t shy about indicting the industry at large for its systemic biases, she’s more selective in sharing her thoughts about particular projects. When she does pull back the curtain, she digs deeper than behind-the-scenes dish or cute stories on set. Discussing her audition for Vera in “Seven Guitars,” the August Wilson play that became her Broadway debut, she poignantly connects the experience to her troubled past.

“It was a beautiful scene of hurt, pain, longing, love,” she writes. “It was me. It didn’t require much for me to tap into that part of myself.” Davis also offers enthralling insight into her experiences on “Doubt,” “Fences,” “How to Get Away With Murder” and “The Help,” a film she questions creatively while still expressing adoration for her collaborators.

By the time Davis gets to her stay at George Clooney’s Italian villa, the cartoonishly lavish experience reads not as an out-of-touch fantasy but a well-earned respite for someone whose road to prosperity was paved with pitfalls. The sweet courtship between Davis and her husband, actor Julius Tennon, also makes for a breath of fresh air, as does Davis’s ode to her daughter, Genesis, whom the couple adopted in 2011.

While “Finding Me” can be docked for loose ends, stilted prose and superfluous anecdotes, Davis’s journey overpowers them. Tethering her past pain to her present, she writes: “I’m no longer ashamed of me. I own everything that has ever happened to me. The parts that were a source of shame are actually my warrior fuel.” That checks out: Whenever it feels like Davis has given her all, she always seems to have something left in the tank.