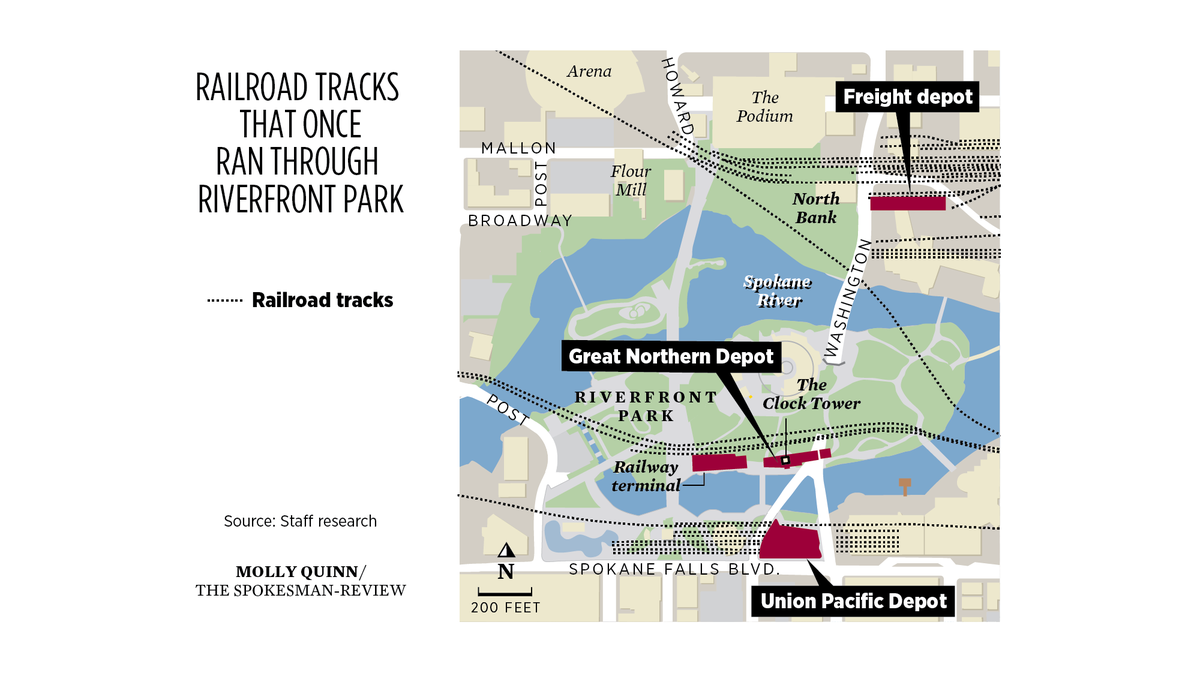

Getting There: The beginning of the end for Spokane’s riverfront railroad tracks was 50 years ago this week, but it was ‘the beginning of the World’s Fair’

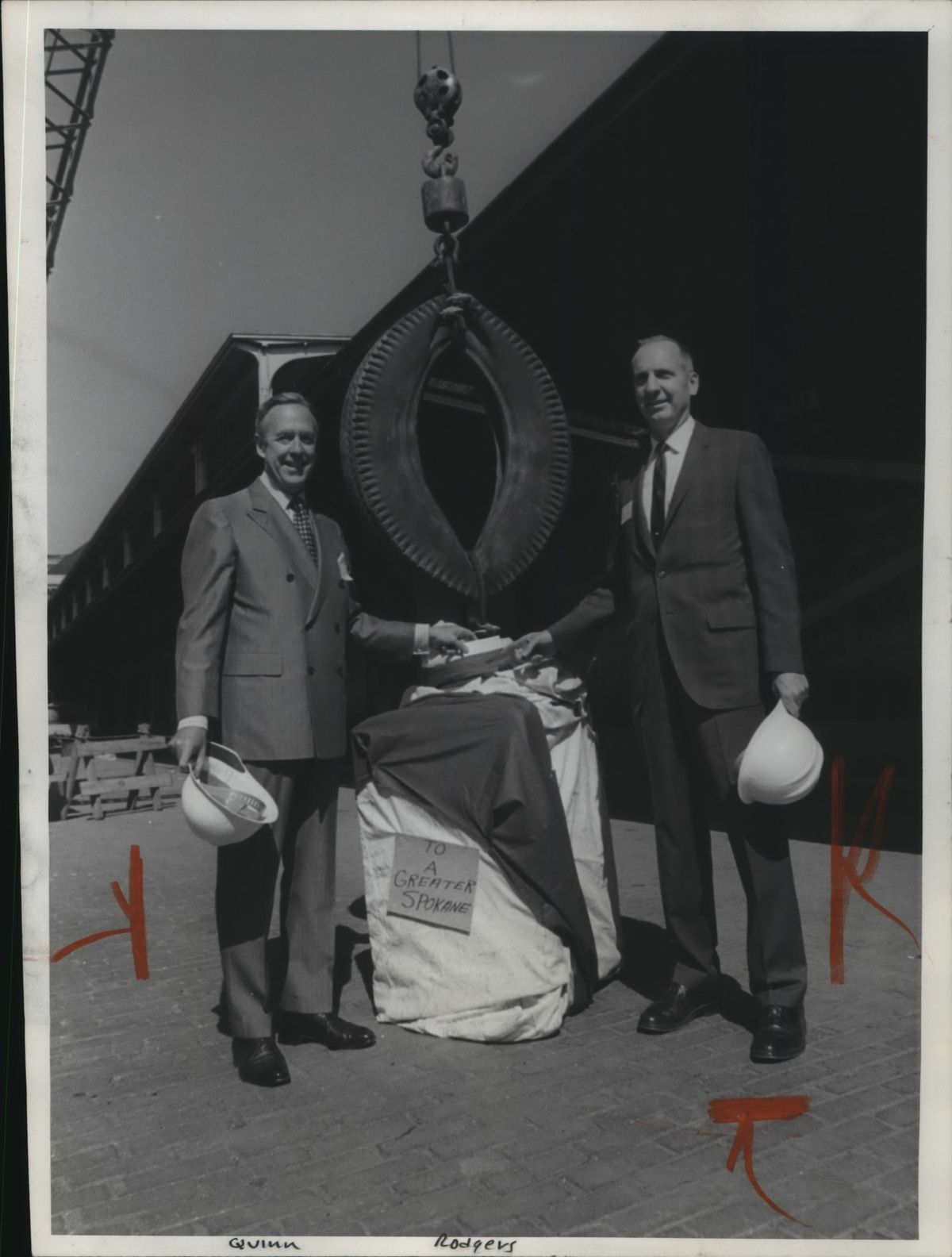

Milwaukee Road official William J. Quinn, left, and Mayor David Rodgers stand next to a decorated wrecking ball prior to a ceremony marking the beginning of demolition of the railroad lines through what is now Riverfront Park in June 1, 1972. The wrecking ball didn’t make it through the ceremony, falling off the chain shortly after its first use. (Cowles Publishing)

The railroads, the public and lawmakers were all on board roughly 50 years ago when the old trestles in the middle of downtown were ready to be torn down.

Everyone seemed to be on the same page, including Mayor David Rodgers and a representative of the Milwaukee Road line that had just deeded land to the city for its permanent downtown park.

Everyone except the decorative wrecking ball employed for a ceremony marking the occasion.

“The ceremony ended, to the amusement of spectators and the chagrin of Glen A. Yake, assistant to the city manager-engineering, when the wrecking ball fell off the end of the chain,” The Spokesman-Review reported on June 2, 1972. “ ‘Great show, Glen,’ someone observed. ‘At that rate you should have it down sometime before Expo ’74 opens.’ ”

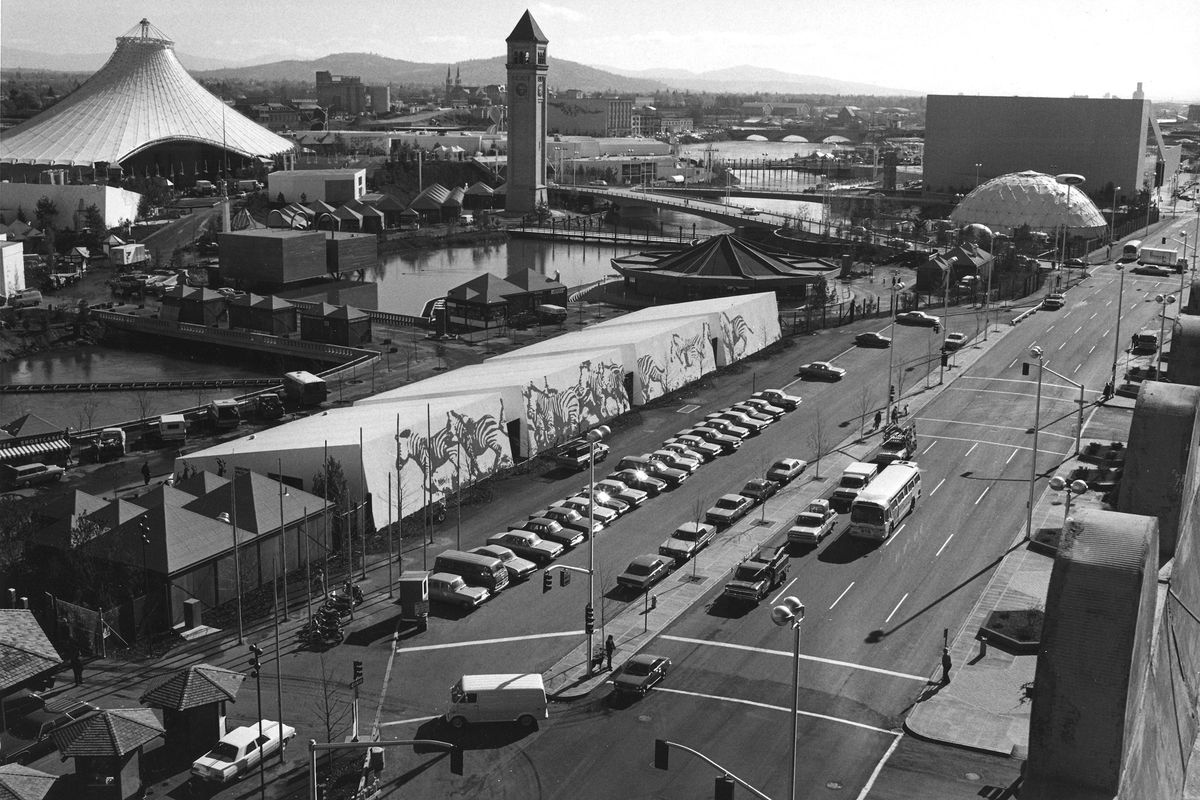

The first contract between the city of Spokane and a company tasked with removing thousands of pounds of steel, concrete and brick was agreed to at the end of April 1972. That $110,000 agreement with Cleveland Wrecking Co. out of San Francisco kicked off a flurry of urban removal through the rest of the calendar year, all to make the May 4, 1974, opening date of the Spokane world’s fair.

The removal of the tracks had been a foregone conclusion since the merger of four lines to create the Burlington Northern Railroad in 1970.

A year later, Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern agreed to share tracks that rendered the trestle along Trent Avenue redundant and allowed for its removal in two phases over much of 1972.

Still, Expo planners in the initial stages had to consider any contingencies. David Evans, the chief site designer for the world’s fair, said he had some initial drawings for the space that included the two railroad depots and part of the trestle.

“We weren’t positive, at the beginning, if we could get all of that out of there,” Evans said in an interview last week.

When demolition began, metal dealers estimated some 35,000 tons of steel would need to be removed from the area, not to mention the concrete in the existing buildings: the Crystal Laundry building, a crematorium, a motel and more.

Expo ’74 also required a land swap from Burlington Northern to give the city the land along Trent Avenue, now Spokane Falls Boulevard, that would act as a southern entrance to the park. Bob Downing, who worked for Burlington Northern and helped facilitate the deal, told The Spokesman-Review in 2008 that he was personally asked by the rail line’s chief executive to make the deal happen.

“The land would have sold for a lot of money,” Downing, who died in 2010, told the paper, “but the railroad thought that this was something we could encourage, so we did a trade.”

Evans, who spent many days trekking over the tracks on Havermale Island as he sketched what the world’s fair might look like, said the cooperation embodied what Expo ’74 was about.

“There’s something almost miraculous about it,” Evans said.

Though the tracks themselves were an easy sell to remove, what to do with the two standing depots wasn’t as simple.

Jerry Quinn, a railroad buff who came to Spokane by way of New Jersey, found himself the face of a group called Save Our Stations that sought to preserve the buildings from that (initially ineffectual) wrecking ball.

“I thought the heritage of Spokane was tied up in those stations,” Quinn, who received recognition from the city last fall for his work to preserve the clock tower from the Great Northern depot, said in an interview last week.

Both Quinn and Evans noted the importance of the railroad in Spokane’s history. The method of travel had begun to be overtaken by the airplane in the late 1960s. The movement of freight became the focus of the lines that remained in Spokane.

Quinn wasn’t sad to see the trestles go. But 50 years later, he’s still upset about how the city went about selling the demolition of the buildings. If views of the Spokane River were the reason for demolishing the depots, he said, why are large buildings now being built in proximity to Spokane Falls Boulevard?

“When I talk about the clock tower, people say, ‘There were trains here? That was a railroad station?’ ” Quinn said. “There’s no knowledge, no information.”

Evans said the preservation of the clock tower kept “the best of that building.” It makes an appearance in a Christmas card the Expo boosters put out in 1972, featuring a pencil sketch Evans made of the depot demolition.

“This represents the beginning of the removal, the beginning of the World’s Fair,” Evans said.

King Cole, the tireless booster of the exposition, would later tell the writer William T. Youngs, for his book “The Fair and the Falls,” that even if Expo ’74 didn’t come together, he would have a lasting effect on Spokane’s skyline.

“I felt like, if nothing happens, if the fair didn’t happen, if I died, whatever happened, what I really wanted to do most of all was to get rid of those damn tracks,” Cole told Youngs.

Work to watch for

Shoulder closures will continue this week on Post Street near Corbin Park at the intersections of Fairview, Park, Frederick, Euclid, Dalton, Alice, Cora, Kiernan, Providence, Garland and Walton avenues for the installation of accessible curb ramps.

Traffic will be shifted on Fifth Avenue as part of the Thor/Freya couplet construction to the south side of the intersection. Parking will be limited.

As part of Spokane County’s ongoing Bigelow Gulch project, Progress Road from the intersection of Progress and Bigelow to the intersection of Crown and Progress will be closed until Oct. 31, with a detour in place.

WSDOT reports construction along the shoulder of the eastbound lanes of Interstate 90 at mile post 277 near the intersection of U.S. Route 2 will continue until further notice Mondays through Thursdays.