Montana’s Matson’s Laboratory on forefront of wildlife dental data

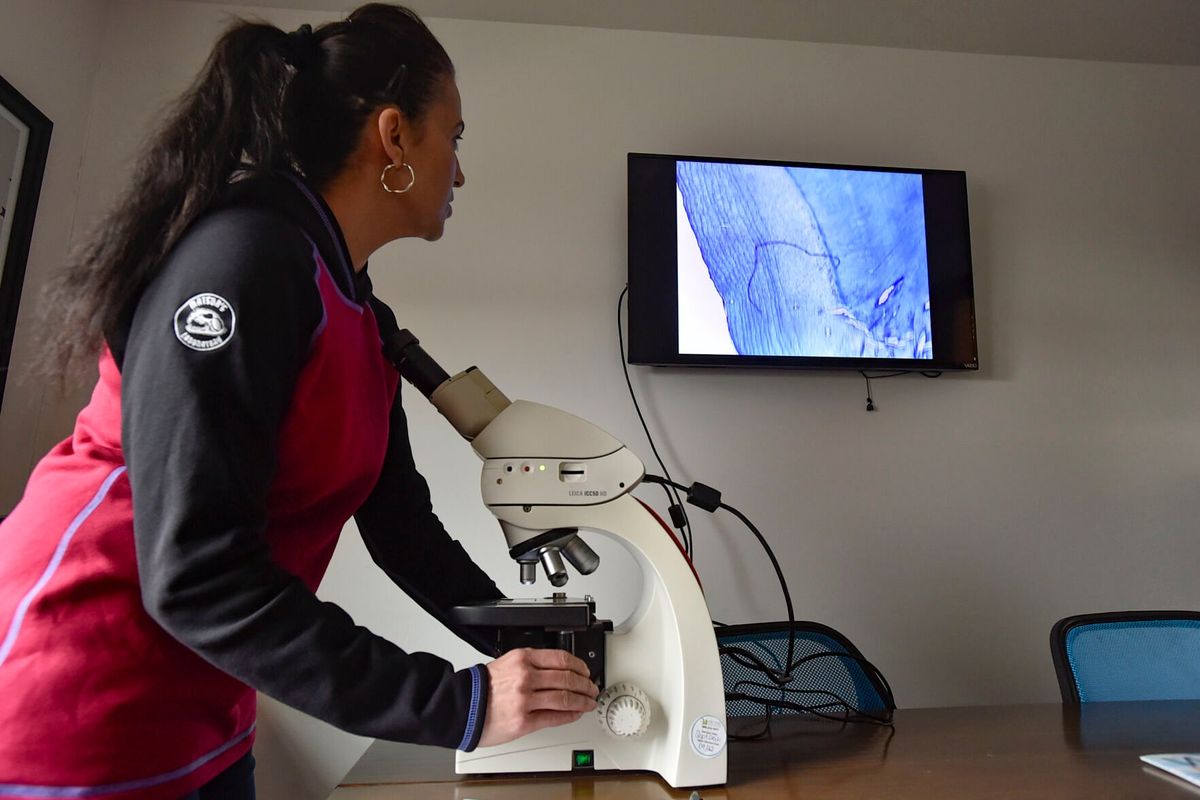

Carolyn Nistler demonstrates with a digital microscope how to identify and count growth rings in a tooth at Matson’s Laboratory in Manhattan, Mont. (THOM BRIDGE/Independent Record)

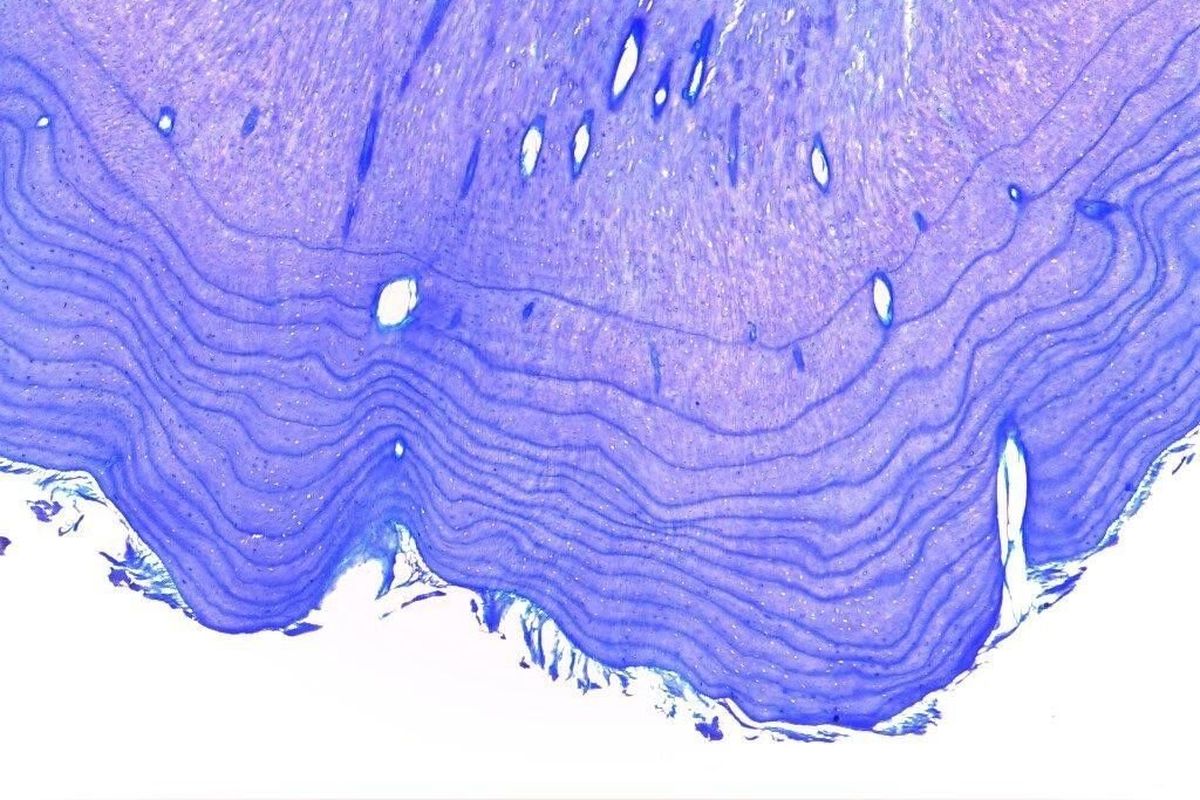

MANHATTAN, Mont. – With the microscopic image projected onto a screen, Carolyn Nistler quickly tallied up age rings resembling the contoured elevation lines of a topo map, arriving at the age of 14 for this northern European lynx.

“If they all looked like this, our jobs would be so much easier,” she said. “That’s just gorgeous growth, you couldn’t ask for a better example.”

Nistler owns Matson’s Laboratory in Manhattan, which specializes in cementum age analysis of wildlife teeth. As a tooth grows, tissue called cementum forms on the outer layer of the root. Much like the growth rings on a tree, environmental stressors cause dark layers of cementum, forming rings called annuli. Under a microscope and using the body of knowledge about how species or regional animal populations grow and when certain teeth “erupt” from the gumline, Matson’s cementum age analysis provides accurate data used to track wildlife populations or learn more about individual animals.

In 1969, Gary Matson opened Matson’s Laboratory in Milltown, Montana, developing many of the techniques still used today. Nistler, who holds a master’s degree from Montana State University, was running a wildlife consulting business when she met Matson at an aviation conference in 2013 – they are both pilots.

From that meeting, Nistler would learn techniques from Matson and buy the lab in 2015, moving it to the Manhattan location just off Interstate 90. There she has cultivated an atmosphere that feels more storefront than laboratory – workers wear no lab coats, and the quiet beat of 1990s hip-hop thumps on speakers – but here some of the foundational work of wildlife management and research is taking place.

“We want people to come, we want to share what we do with them, because it’s so important to the wildlife in our state and the wildlife everywhere,” Nistler said. “We really believe in what we do and why the data is important.”

The bulk of Matson’s teeth come from wildlife managers or research projects. Biologists use age data to monitor or study wildlife populations, removing a tooth from sedated animals or hunter harvests. The information may be used to justify hunting seasons, adjust quotas or learn more about age structure or reproduction.

Teeth arrive at the lab in envelopes – beluga whales from Canada, brown bears from Croatia, whitetail deer and black bears from across the United States – where technicians begin the weekslong process. Teeth are sorted, cleaned and decalcified in a partially proprietary process, emerging in a rubbery state that allows razor-thin cross sections to be cut. These cross sections are placed on slides, stained and receive a cover slip before going under expert eyes for aging.

“It’s very niche, but it’s very cool because – even though it is so specific and particular – it gives us a chance to be involved in wildlife research and conservation throughout the world right here from our little lab in Manhattan,” Nistler said.

The lab processes about 400 teeth a day and 110,000 each year. Matson’s is closing in on a milestone of 3 million teeth since Matson opened the lab, expected to be eclipsed this year.

Matson’s has continued to improve its process and build species profiles to aid in aging. That includes updates on technology, usually in the form of incorporating automation for certain steps in the process such as placing cover slips on the slides.

“(Technology’s) been helpful, but one of the things we’ve learned that’s really important is that there’s a lot of this stuff machines can’t do,” Nistler said. “You still need a human to check because each species takes up the stain a little bit differently.”

Nistler removed the slide from the 14-year-old lynx and replaced it with a new slide.

Unlike the first cat, this specimen was far more ambiguous and took her bulk of knowledge of the species to arrive at an age range of 2-3. When an exact age is not definitive, Matson’s assigns an age range as its best determination.

“Sometimes we can tell in a split second,” she said. “And sometimes I spend 5 or 10 minutes on a sample trying to assign the correct age because that’s just the nuance.”

Nistler counts river otters and mountain lions among the more difficult wildlife teeth to analyze. Knowing not only the typical characteristics of a species, but also differences in range, is a major part of arriving at an accurate age. In Texas white-tail deer for example, the annuli are less distinguishable, while deer living through the harsh winters of northern latitudes display clearer growth rings.

Sexes can also vary, and females may display differences in years where they produce young. Nistler suspects either hormones or the sapping of the mother’s resources accounts for those distinctions.

Most teeth come from state wildlife agencies, but Matson’s has seen a surge in teeth provided by individual hunters in recent years who simply want to learn about the animals they pursue. Matson’s offers detailed instructions for how to remove a tooth and submit it for aging and charges $75 for up to five animals.

“We’re hunters, we believe in hunting as a conservation tool,” Nistler said. “Hunters are definitely wanting to become more informed of the role they play, and age is part of that.”

Shannon Bell is an avid hunter from Helena and a Matson’s customer. He recalled shooting an older mule deer buck in Montana and a massive bull moose in Alaska that had him wondering about age – Matson’s put the buck at 7 and the moose at 12. Hunters often look at physical characteristics of animals such as body size to estimate age, but having those assumptions verified helps him better understand what he is seeing in the field.

“Just as a hunter, it’s very interesting to understand more about your quarry,” he said. “You think about how many winters he made it through … and I think it just educates the hunter. We’re stewards of the animals and, to be honest, it’s also super cool and was just really fun.”

While cementum aging is Matson’s primary work, Nistler also offers several other services, including ovary analysis, which can estimate size of litter and timing of pregnancy, and tetracycline biomarker screening used in rabies vaccine tests for raccoons and mark-and-recapture studies for black bears.

The lab also provides skeletochronology preparation, primarily for amphibians, which cross-sections toe bones found to have growth rings.

Matson’s is using skeletochronology to analyze python and black bear rib bones as well.

“Every living animal has some part of their body that’s influenced by annual growth cycles, it’s just figuring out where it is,” Nistler said.