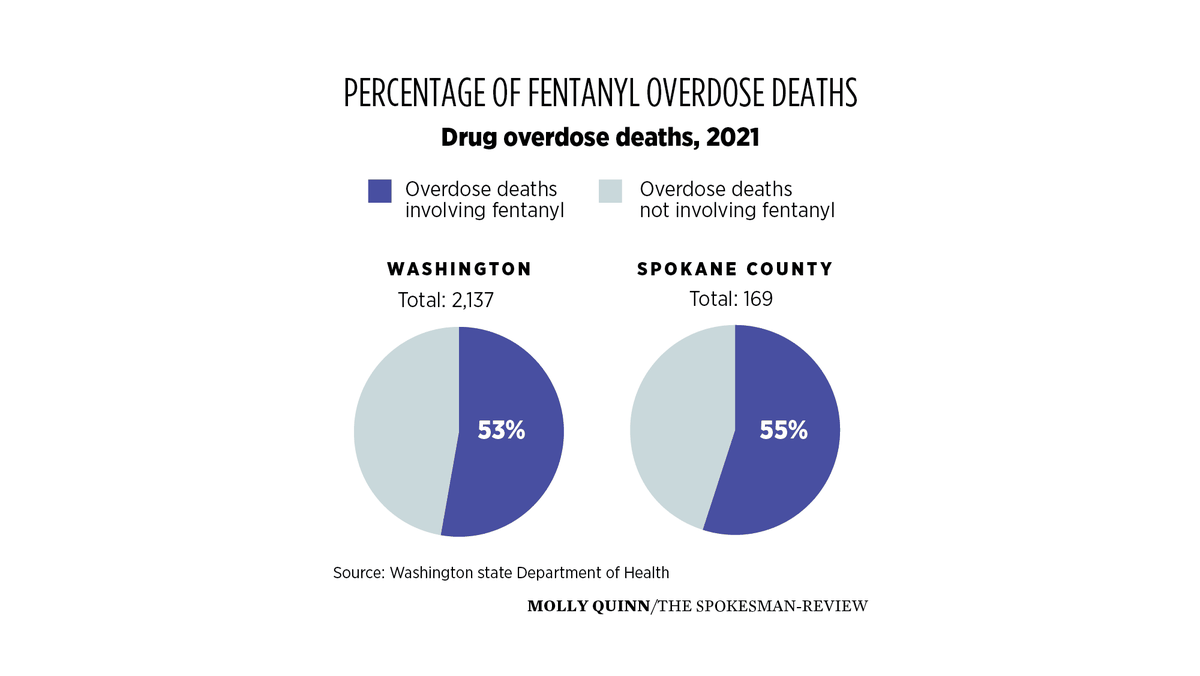

Fentanyl involved in more than half of overdose deaths in Washington state and Spokane County in 2021

Spokane County Sheriff’s Office deputies seized fentanyl, oxycodone, methamphetamine, drug paraphernalia and cash during a traffic stop in mid-April. (Courtesy of Spokane County Sheriff's Office)

Deaths from fentanyl overdoses in Washington have increased by 845% in the past five years.

In 2017, 120 Washington residents died of an overdose involving fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid that has flooded the illicit drug market in Washington state.

In 2021, 1,134 residents died from fentanyl overdoses, more than half of the overdose deaths reported, according to the Washington Department of Health.

In Spokane County, 93 of the 169 reported drug overdoses in Spokane County last year involved fentanyl.

And the problems seems to be worsening. In March 2022, EMS units in Spokane County responded to 153 possible overdoses, 102 of which involved opioids.

“The exponential increase in deaths is due to exponential increase in availability of fentanyl,” said Dr. Bob Lutz, adviser with the Department of Health.

At this point state public health officials are warning residents that any substance not obtained from a pharmacy or licensed marijuana retailer may contain the highly addictive and potentially deadly opioid.

“You have to assume fentanyl is in what you’re taking,” Lutz said.

What makes fentanyl different

The opioid crisis has been ongoing for years, with prescription opioids flooding the market and leading many to addiction. But fentanyl is different from oxycodone or hydrocodone.

Just 1 or 2 milligrams of fentanyl can cause an overdose, a small amount that often goes undetected if it’s laced into a different substance.

Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than morphine, said Dr. Nicole Rodin, professor at Washington State University’s College of Pharmacy.

Because fentanyl is more potent, it releases more dopamine in a person’s brain and works quickly. It also persists in the body longer than other opioids.

The effects of fentanyl can produce a rapid high and then rapid low, making a person think they need more to maintain the high. The problem? Fentanyl stays in a person’s system longer than that.

“While the amount you’re taking is more and more, it hasn’t left your system, and people are adding more drug on top of a filled system and as a result they overdose,” Lutz said.

The widespread availability of fentanyl also means the already-present need for addiction treatment could grow in the coming months.

The demand for treatment grew during the pandemic, and local providers see a need for more physicians to offer opioid use disorder treatment, more detox beds and more services for people struggling with addiction and mental health disorders.

Addiction is a disease of the mind, rewiring the pathways in your brain to manipulate your reward system, and as Rodin points out, it can be treated when people are ready for it.

“The good thing is with abstinence and decreased use over time, your brain can go back to normal,” Rodin said. “You can rewire those pathways with treatment, and that’s pretty hopeful and a huge takeaway.”

Increasing access to evidence-based treatment, like medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders, is also important, she added.

“We still have a lot of treatment centers that are unwilling to provide (treatment) to patients,” Rodin said.

Investing in education, prevention

Preventing overdoses and deaths starts with education.

Rodin, who serves on the Spokane Alliance for Fentanyl Education, said that these conversations start at home, between parents and teenagers.

Alerting teenagers to the inherent risks of fentanyl showing up in substances they might get illegally is not going to encourage them to seek the drug.

“Just because you start the conversation doesn’t mean you start the ideation; in fact, we know it’s quite the opposite,” Rodin said.

Social media and innovation have led some teenagers to believe they are being careful, but some of these tools are now much less helpful.

Phone apps that identify types of pills, Rodin said, will not be able to show if a pill is laced with fentanyl. Local families have experienced that painful reality, as they have lost teenage children to misidentified pills, thinking they were taking a different substance and subsequently overdosing.

Recently, local police have found pills that look like prescription narcotic, called mexi-blues, are often laced with fentanyl.

The Department of Health is working to launch a public awareness campaign around methamphetamine and fentanyl for youth and adults, with $2 million in funding from the Legislature.

The campaign will focus on harm reduction to prevent addiction and deaths, including education about naloxone, which is used to treat overdoses.

Reversing

overdoses

While fentanyl overdoses can be lethal, they don’t have to be.

Naloxone, a drug administered as a nasal spray sometimes identified by its brand name Narcan, can reverse the effects of a fentanyl overdose and save a person’s life.

From April 2019 to this February , the state health department received reports of 9,840 overdose reversals by laypeople because of efforts to distribute naloxone widely. These are self-reported numbers, which means there could have been even more overdoses in that time.

At the Spokane Regional Health District, the treatment services and syringe services programs give out naloxone kits. In 2021, both programs gave out 2,203 naloxone kits that resulted in an estimated 855 overdose reversals.

In March , EMS units administered naloxone 67 times in Spokane County, and it improved the response of the person, a state health department report shows.

The state would like to get even more naloxone out into communities. The Department of Health is working in more than 30 counties with about 200 organizations, including syringe services programs, housing organizations, community health clinics and school districts.

Due to the potency of fentanyl, sometimes an overdose may require multiple doses of naloxone to be reversed.

Because naloxone has a shorter half-life than fentanyl, a person might wake up from an overdose after receiving naloxone but then go back into overdose, Rodin said, and learning how to properly administer naloxone as well as always calling 911 if you’re administering it are both practices she encourages and teaches.

As overdose deaths due to fentanyl continue to increase, stakeholders say everyone needs to be prepared for an “all-hands-on-deck” approach.

“If you’re a venue where people are partying, if you want to keep people partying safely, you should have naloxone and people on your staff should be trained in using it,” Lutz said.

This is happening elsewhere on the West Coast.

Bars in San Francisco have started to stock up on both naloxone and fentanyl testing strips, after a number of overdoses resulted from people using cocaine laced with fentanyl.

There is a statewide standing order in Washington for any person to get naloxone at a pharmacy without a prescription, and health officials encourage anyone who is around people using substances to carry the nasal spray with them.

Testing substances

Fentanyl strips, which can be used to detect fentanyl in a substance when mixed with water, are another strategy to potentially prevent overdoses.

Some health districts in Washington participated in a pilot program to administer fentanyl strips from 2018 and 2019 at syringe services programs. Test strips affected how people used substances, according to the syringe services director at SRHD, with many participants reporting back that their tests were unexpectedly positive.

Recently, SRHD had stopped distributing fentanyl strips “out of an abundance of caution” according to their legal counsel for about two months.

A law passed in the 2021 legislative session changed this, however.

Senate Bill 5476 decriminalized some drug paraphernalia for specific purposes, including testing, which would apply to fentanyl test strips, according to Department of Health spokesperson Frank Ameduri.

In the last week, SRHD changed course, however, and after an internal review, the district starting to distribute fentanyl strips again.

Other health districts in the state have been distributing fentanyl strips all throughout 2021, and the Department of Health confirmed that both state and local health departments have the authority to distribute fentanyl test strips.

King County Public Health distributes fentanyl test strips to community-based organizations including syringe service providers and needle exchange programs.

Since March 2021, that district has distributed 37,000 test strips.

Of course, no test is perfect, and health officials are warning that any illicit substance, even in pill-form, could be laced with fentanyl.

Ultimately, harm reduction strategies and prevention strategies are what health agencies and stakeholders, like Rodin, are advocating for to fight back against the wave of fentanyl in the community.

“We know programs like DARE didn’t work: the scare tactics, the abrasive stuff didn’t work and didn’t prevent deaths or addictions in any way shape or form, so now one of the primary pillars of prevention is the education piece so really getting in there and being transparent is key,” Rodin said.

Reducing overdose deaths through harm reduction also acknowledges that humans are going to choose to behave in a certain way as well as acknowledging how addiction works, too.

“Now the message really has to be, knowing you’re going to do it, if you do it, do it safely,” Lutz said.