Addressing mental health and suicide for teens, as survey data show increased challenges following pandemic

WILBUR, Wash. – “How many people know someone struggling with a mental health condition?”

Nearly every hand raised in the Wilbur-Creston High School classroom on Monday, in answer to this question.

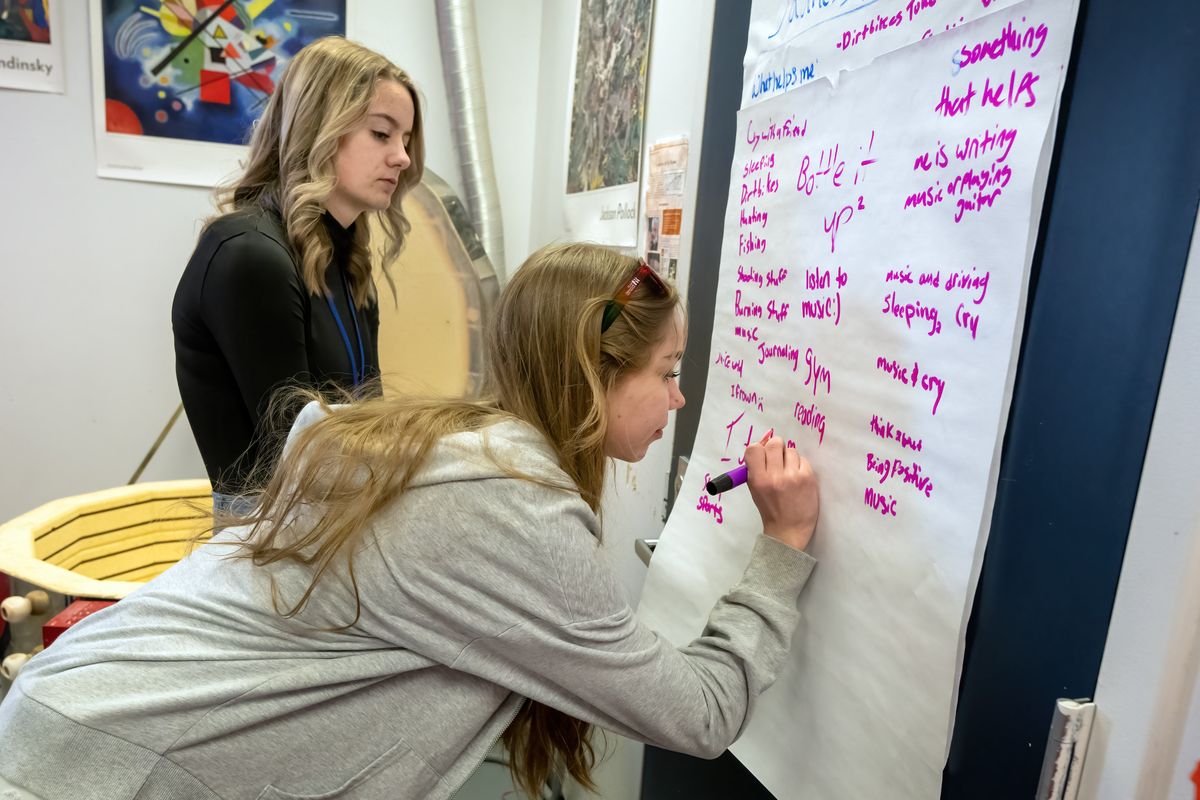

On the first day back after spring break, high school students and eighth-graders did not return to their normal subjects but instead participated in Wellness Day, an initiative to address some of the students’ struggles with mental health, bullying and harassment.

Students learned about the warning signs of suicide and that it’s OK to ask the question “Are you thinking about suicide?” of their peers.

Kalen Via, a volunteer with National Alliance on Mental Illness Spokane, shared her experience getting panic attacks toward the end of high school. She sought help from her parents and doctors, who diagnosed her with anxiety panic disorder.

With therapy and the support of a peer struggling with a similar diagnosis, Via told the high school students about how she learned to share her experiences with others and utilized therapy, breathing exercises and dietary changes .

Via, now 27 years old, told the class that she wished she had others around her when she was growing up who were willing to share their struggles.

She’s helping to be a part of the solution, confronting the stigma around talking about mental health and suicide.

“We’re giving them the words,” Via said.

‘It’s been an intense year’

At Wilbur-Creston High School, the focus on mental health and suicide is intentional.

When Principal Belinda Ross got back student results of the Healthy Youth Survey , mental health became a top priority for her and her team.

In Lincoln County, the majority of high school students and eighth-graders surveyed felt anxious in 2021; among high school seniors surveyed, 44% of them stopped doing their usual activities because they felt so sad or hopeless for two weeks or more.

High school and middle school students at Wilbur-Creston School are not unique; they are experiencing what their peers throughout the state and country are feeling in the wake of the pandemic.

State data mirrors what national surveys have found: The pandemic severely impacted children’s and teens’ mental health.

About one in three high school students experienced poor mental health during the pandemic and in the past 30 days, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey found. Further, nearly 20% of the students surveyed by the CDC had seriously considered attempting suicide.

Even before the pandemic, Ross knew her students were struggling, but things got even worse when the schools shut down.

It was difficult to keep tabs on students and their families from a virtual school setting, but Ross prepared for fall 2021 when students returned for in-person classes. The entire school staff took mental health first-aid training specific to adolescent and teen populations.

For two months last fall, Ross said staffers were responding once or sometimes twice a week to students who had thought about or attempted suicide. In a school with counselors in the building only some days, that meant it fell to other staff to find resources and referrals for students.

From wait lists to insurance, the need far outweighs the available providers or services.

“Parents are so overwhelmed trying to find resources,” Ross said.

Beyond students struggling with suicide, the community has also been grieving. Ross said some students have lost parents to COVID-19 , and the school lost one of its own teachers to the virus as well.

“It’s been an intense year,” Ross said.

Springing into actionThe Wilbur-Creston School District applied for state funding through the Health Care Authority to bring in more support for their students.

The grant came from the Community Prevention and Wellness Initiative, which provided a student assistance professional and a community coordinator, through NorthEast Washington Educational Service District 101.

The state funding aims to provide support to students both in the classroom and outside of school.

“Ultimately the hope is you enroll the student as an intervention student, identify concrete goals, screen them for substance use, mental health and risky behaviors, and start to work on those goals, and in 12 weeks ideally you’re moving them out,” said Brittany Campbell, director of the Center for Student Support at ESD 101.

The Wilbur-Creston School District just got its on-the-ground staff support earlier this year from the initiative, and Ross as well as other staff members wanted to hit the ground running.

Within three weeks of coordinating with community partners, Wellness Day was on the calendar.

Casey Clark, a behavioral health counselor at Wilbur-Creston School District, said the idea of Wellness Day had been one she’d thought of long before COVID-19, but with the added support from state funding and additional staff members, they could finally make it happen.

Clark is seeing what many other school districts are seeing: “an uptick in suicidal attempts, ideation and concerns, depression and anxiety and also a big uptick in harassment, intimidation and bullying especially online, or through the use of social media,” she said.

In coordination with community partners, project leaders created sessions for Wellness Day around these concerns: harassment and bullying; mental health and suicide prevention; team-building; and social media use.

Students rotated through each of these sessions on Monday, in addition to visiting booths from community partners.

Billie Wheeler, the community coordinator in Wilbur, had organized stakeholders connected to wellness, from the hospital to the public pool and every organization in between. Students visited each booth to learn about services and pick up freebies, like pens or stress balls, throughout the day.

Resources in the community

Mental health resources, like therapy or telehealth counseling, are harder to come by in rural areas.

Part of Wellness Day was about bringing together some of the community providers offering mental health services.

Karen Keith, the new behavioral health care manager at Lincoln Hospital and Clinics in Davenport, Washington, has already seen three teens in her practice since starting her job there a few weeks ago.

Keith met other mental health providers at their booths , noting how important it was to form alliances and be able to refer to one another when they have no room or space in their programs.

Keith is only seeing established Lincoln Hospital patients for now, but she plans to expand the hospital’s behavioral health resources by starting up therapy groups and an intensive outpatient program. She said she expects this is only the tip of the iceberg in how the pandemic has impacted kids.

“These kids have experienced trauma,” Keith said. “My biggest work will be to address the trauma causing the anxiety.”

At the Health Care Authority, the Healthy Youth Survey is used to help target funding to schools where students need the most support for mental health or substance use.

The most recent survey results show that mental health needs among pre-teens and teens in the state persist, and suicide remains the second leading cause of death in 15- to 19-year-olds, said Sarah Mariani, a Health Care Authority manager representing the area’s behavioral health division.

The state survey showed the majority of teens have trusted adults in their lives they can turn to as well as some amount of hope.

“Around 70% of students reported higher rates of hope,” Mariani said.

The goal of Wellness Day, Clark said, was to empower students to have conversations, learn about resources, ask for help and support one another.

“We can do a long-term curriculum, but we also need to give them a big dose of a lot of healthy things, because there are so many kids experiencing so many different struggles,” Clark said. “To make it so they can see they’re not alone in their struggles and support, we’re all here for them.”

School districts, like Wilbur-Creston, are connecting students to resources for substance use and mental health care, in addition to instruction in all of the regularly required subjects.

And while that might sound like more than a school district’s mission, the last few years have distilled a truth for Ross about her students.

“If they are not healthy, they cannot think,” she said.