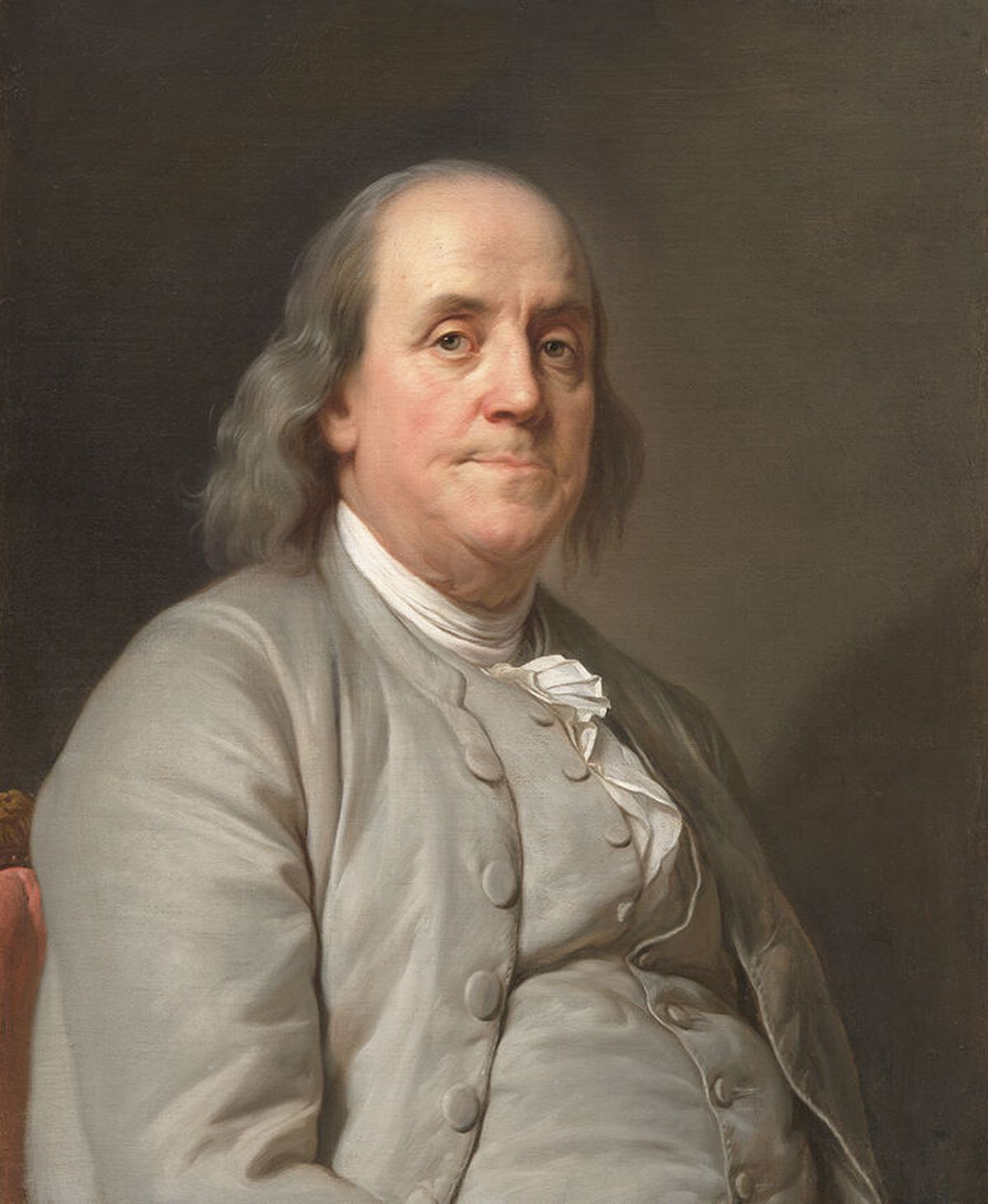

We the People: Ben Franklin, the financier? How the founding father’s less-publicized talent is still helping people today

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Benjamin Franklin is famous for many things. Name one.

Benjamin Franklin is known for his work in crafting the founding documents of the United States, contributing to our understanding of electricity and serving as a Revolutionary War-era diplomat in France. But there is a perhaps lesser-known, but long-lasting, element of Franklin’s legacy: a small loan program for trade workers.

Franklin’s life was the subject of a two-part, nearly four-hour program that premiered on PBS this past week. The Ken Burns-produced documentary took a close look at Franklin’s numerous works in the fields of writing, science and international diplomacy, but only in the last two minutes of the piece was there a passing reference to his loan program.

Michael Meyer, author and professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh, takes a closer look at the loan scheme in his upcoming book, “Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet.” Franklin saw the loan scheme as his “blueprint for American prosperity, both economically and politically,” Meyer said.

“Most people, when they think of Benjamin Franklin, they think of science, they think of diplomacy, maybe they think of his writing because he wrote the first American memoir,” Meyer said in an interview. “But I think very few people think of his philanthropy.”

In his last will and testament, Franklin left 1,000 pounds sterling each to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia to administer a program awarding small loans to trade apprentices looking to start their own businesses, Meyer said. The loans would have a minimal interest rate and be paid back over 10 years – similar to how microloans exist today.

While it’s difficult to calculate how much those initial amounts would be valued at today, Meyer said they had the “purchasing power of tens of millions of dollars.”

Meyer said the will also stipulated the cities had to manage the loan program for free. At the centennial and bicentennial anniversaries of Franklin’s death, the cities were allowed to dip into the funds and “democratically decide” how they could use it for the common good.

“I love the idea of him thinking like, ‘Yeah, in 100 years maybe they’ll have sorted this democracy thing out where the cities can come together and democratically agree on what to spend this money on,’ ” Meyer said.

Franklin picked up the idea from a French essayist who wrote to him about a man who made a lot of money through compound interest and later put it toward investments in society, Meyer said.

As he reached the end of his life, Franklin recalled the essay, put his own spin on the idea and included it in his will. Meyer said the loans were Franklin’s way of passing his values down to future generations and passing on the good fortunes that had been afforded to him.

“In the will, he said, ‘You know, I received help starting my business – someone staked me. So, I want to pay that forward and do the same,’ ” Meyer said.

The loans targeted trade workers, he said, because Franklin wanted them to eventually go into government like he did and “protect the republic” from a growing aristocracy. He believed those tradespeople were best fit to serve because they “interact with all walks of life on a daily basis” and “see the effects of policy and taxation at the ground level,” Meyer said.

While the program was certainly idealistic and may seem simple on paper, it came with its fair share of challenges and complexities.

The first 20 years of the program’s implementation worked well, Meyer said, but the industrial revolution threw a wrench in the system.

The amount of tradespeople eligible for loans dwindled as trades gave way to manufacturing and factory jobs.

Changing economic conditions for Boston and Philadelphia, conflicts during America’s early days and general economic strife led to many defaults in the program, he said.

The cities had their own ways of handling the money, resulting in varying levels of success for the two communities. Meyer said Philadelphia historically struggled to manage and grow its funds, but did well in providing loans for workers. Boston, on the other hand, had its funds professionally managed and prioritized the investment and growth of the money over the distribution of it in loans, he said.

“The Boston money grew more than the Philadelphia money,” Meyer said. “But Philadelphia did a much better job of adhering to Franklin’s wishes in trying to get this to as many working class people as it could.”

There were times where the cities found themselves in court for trying to use the program funds outside the stipulations of Franklin’s will.

Meyer said as he was researching for his book, he thought about how the funds could’ve helped Black tradespeople who couldn’t find work during the 19th century, despite rules that provided equal protections for workers.

“There could have been a concerted effort in the 19th century to change who these loans were given to,” Meyer said. “Although it did go on to help many, many women in the 20th century as nurses, doctors, firefighters and police officers, it could have also been in circulation and changed lives in the 19th century in that regard as well.”

Even with all of those challenges the program faced early on, its money is still being circulated and put to use.

The Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology, a technical school in Boston’s South End neighborhood, was established using funds from the loan program and a matching grant from Andrew Carnegie, Meyer said. In Philadelphia, the “Franklin Fund” provides fellowships for individuals looking to learn a skilled trade or craft.

“The money is still out there,” Meyer said. “Franklin is still with us today.”

While the program was established to support trade workers and eventually get them involved in the political process, the small number of people going into trades and the lack of representation of working-class people in the government today would “shock” Franklin, Meyer said.

Franklin’s example of altruism may be drastically different from today’s notions of philanthropy, but it provides a reminder on how to make a difference, Meyer said.

“The lesson I take away from this is that we should be thinking about Americans 200 years from today,” Meyer said. “You don’t have to do a multimillion dollar gift – build a wing of a college, or endow a chair or something – to have a real impact on people’s lives.