‘For a sacred purpose’: Works by Harold Balazs find a new home at St. Luke Lutheran Church

During Sunday service last week, Pastor Jim Johnson of St. Luke Lutheran Church in north Spokane held a dedication of several key pieces created for the church’s new sanctuary. Among the newly polished objects on the dedication list were an altar, a baptismal font and a 65-year-old series of sculptures called Easter 1-8 created by the late Harold Balazs.

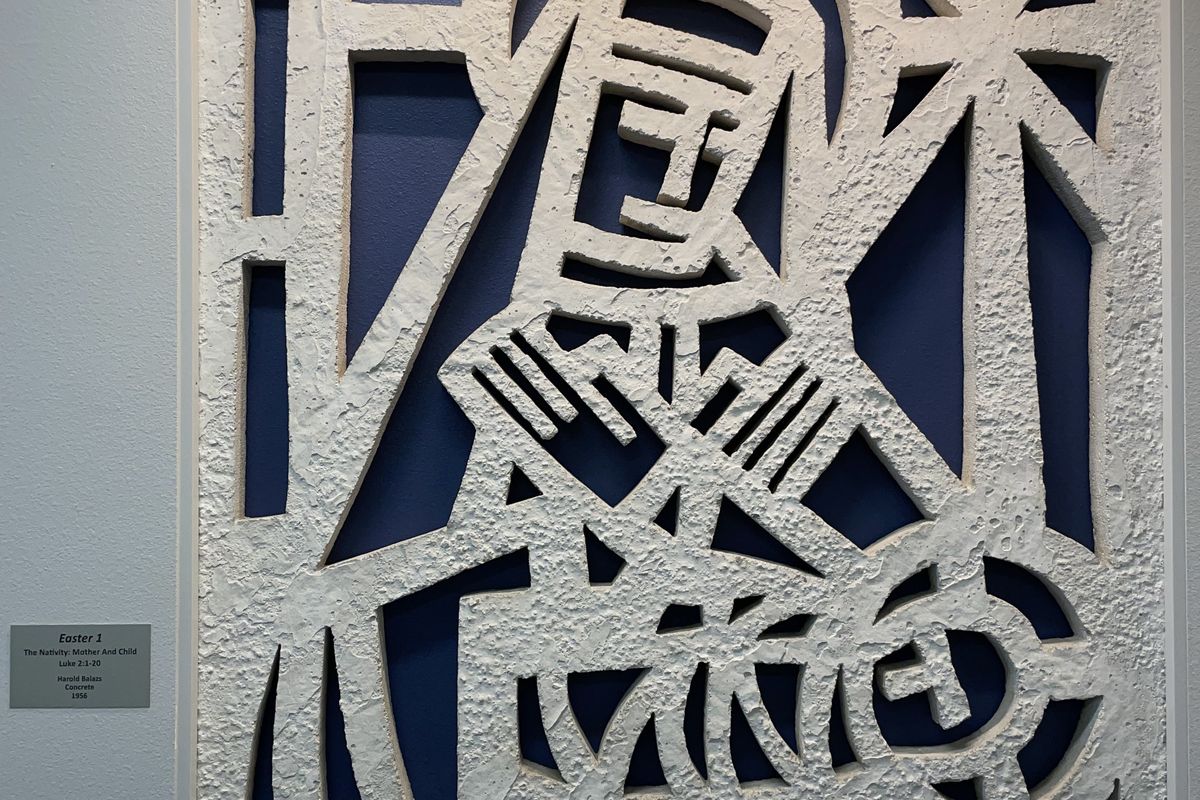

The eight cement sculptures depicting the defining moments of Christ’s life are exquisite examples of Balazs’ brutalist midcentury style. The 3-foot-by-4-foot cast concrete grillwork panels look raw and unadorned, with the tangled forms Balazs made famous.

The sculptures were originally created for Bethlehem Lutheran Church on the South Hill in 1956. But after the church closed in recent years, the Art Spirit Gallery in Coeur d’Alene, which manages Balazs’ art estate, obtained the pieces and spent two years searching for a new home for the liturgical works.

Art Spirit Gallery represented the prolific painter, sculptor, ceramicist, metal fabricator and boat builder for more than 20 years (Balazs, one of Spokane’s most celebrated artists, died in 2017 at age 89).

Art Spirit managers contacted Johnson at St. Luke to see if the pieces might fit into the church’s remodeling plans. Johnson was sure they would. He asked a church member if they would be interested in purchasing the sculpture series for St. Luke.

On the condition of anonymity, the donor wrote a check, and the works were installed this summer in St. Luke’s new art wing. The concrete sculptures were originally made for an outside wall at Bethlehem Lutheran so viewers could look through the window grills, much like stained-glass panels.

However, due to their age and fragility, the works have been hung inside at St. Luke, mounted onto blue backgrounds along a hallway behind the Fellowship Hall. “We have people who grew up at Bethlehem Lutheran who were just thrilled to see this brought here,” Johnson said.

“It was very emotional for them to remember sitting in worship and looking through the windows and seeing these stories.” Recent transplants know Balazs more for his secular works, such as the giant Rotary Fountain he created in 2006 in Riverfront Park, and the 32-foot Lantern he crafted for the downtown Expo ’74 site.

However, in the late 1950s and 1960s, church construction was booming. Local architects became enamored with Balazs’ ability to cast concrete to make all kinds of elaborate and organic-looking designs such as the grillwork for the Easter series. He was also able torch cut iron to create baptistery gates and altars.

Balazs’ unique yet practical techniques brought him fame, work and a steady paycheck as a liturgical artist. He made large concrete sculptures at Spokane’s Messiah Lutheran Church and metal pieces for St. Mark’s Lutheran Church. He crafted 12 enamel panels on the entry doors of St. Charles Catholic Church.

His Bible-inspired sculptures, paintings, stained-glass works and reliefs can be found inside more than 200 Pacific Northwest churches and synagogues. The bulk of Balazs’ income during the midcentury period was from architectural commissions from churches. His daughter Erika Balazs recalled, “I couldn’t have gone to college without liturgical art in this town.”

Interestingly, Balazs himself attended the Unitarian Church, where most left-leaning parishioners believe Jesus was a man, not God. But as an artist, Balazs was always focused on creating beauty, whether it was depicting Jesus’ ascension or creating enamel panels of “Rhododendrons” for Seattle’s Kingdome.

In all these instances, the art tells the story. “That’s why for centuries, churches had so much art on the walls … to tell stories in pictures for the masses who couldn’t read,” Erika Balazs said. “The tradition of art in the church is to tell stories.”

Most meaningful for Balazs’ family members is that the works will be enjoyed in the manner for which they were designed. “My mom (Rosemary Balazs) and I are glad that the pieces were all taken together and not parsed out one by one for sale,” Erika said. “They were meant to be kept together and understood as a whole.”

During Sunday’s dedication, and despite the completion of $8 million in church renovations, Johnson clarified that the bright, shiny objects created for any temple were not “sacred” in and of themselves. Rather, the objects were created “for a sacred purpose.”

Balazs himself would likely agree.