‘They started to connect with themselves and their peers’: Spokane Juvenile Detention Center and Poet Jordan create Art Dojo project for incarcerated youth

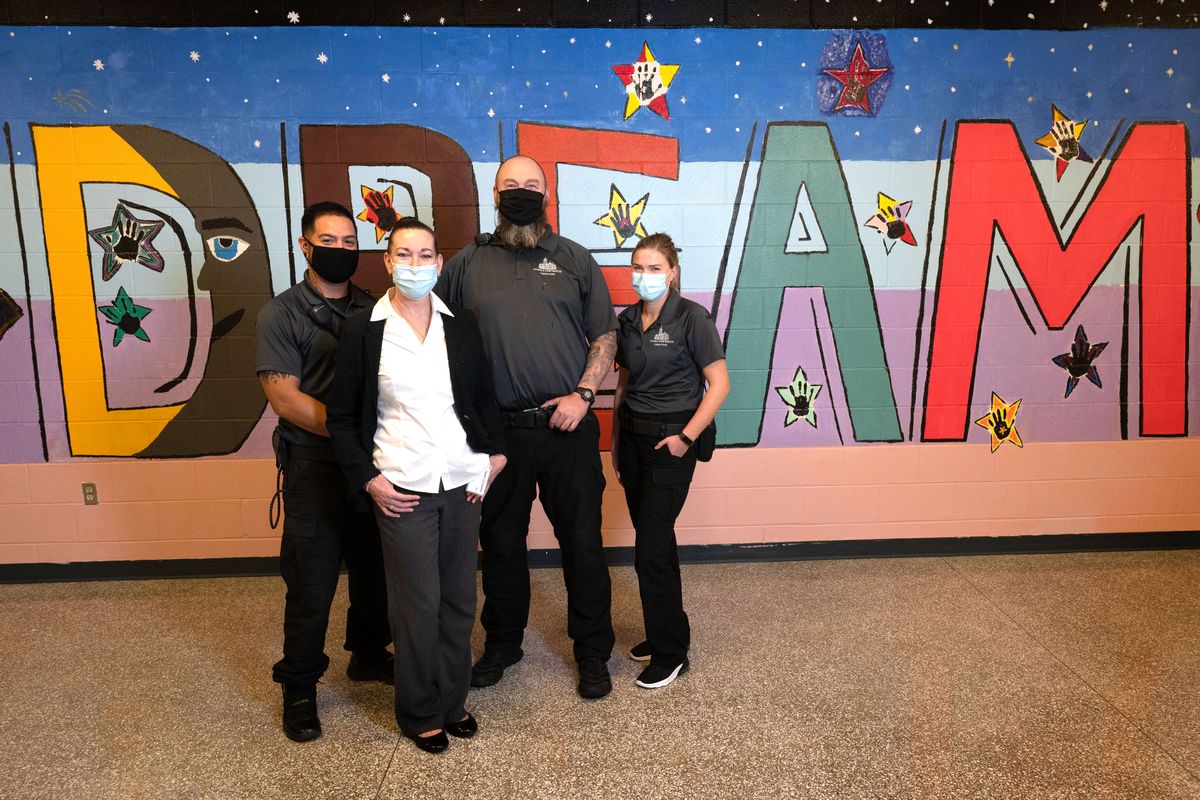

In front, Spokane Juvenile Detention manager Jennie Marshall and, in back from left, juvenile corrections officers Leo Avila, Adam Popp and Cheyenne Konard helped facilitate a mural art project to assist children at the detention center express themselves through art therapy. (Colin Mulvany/The Spokesman-Review)

Sarah McNew, the coordinator of the West Spokane Wellness Partnership, and her colleagues were alarmed by the pandemic’s ripple effects, especially for youth. “We were watching data with mental health among youth and teens skyrocketing,” McNew said. “And that was a concern.”

McNew then asked, if children were suffering mentally at home, what about the incarcerated youth who were stripped of their visitation and other social interactions? That’s when she teamed up with Jennie Marshall, manager of the Spokane Juvenile Detention Center, and Jordan Chaney, known by his artist name as Poet Jordan, to engage in his art therapy project Art Dojo.

Deborah Hanna is the mental health counselor for the detention facility. One of the biggest misconceptions, she said, is that society should treat children like “little adults” when they make mistakes, especially high-risk youth.

“(Art therapy) is a much better option than the ‘Beyond Scared Straights,’ the isolation, the boot camps and all that harsh stuff,” Hanna said. “We know by brain development that they’re not all the way yet, and if we can catch them and guide them along by tapping them into creativity and self-expression, that’s effective.”

Hanna recognized the broadness of art is a benefit since each child can interpret art therapy to their own advantages. She recalled one of the children, who has trouble paying attention, lining each block of Art Dojo’s wall with black paint. The child’s calm and focused demeanor spoke to her desired method of rehabilitation.

Chaney, an Indigenous and Black poet who uses art as a form of therapy, says “Don’t Waste Your Pain(t)” is the motto for Art Dojo. As a former high-risk youth, he relates to the children by telling stories of his time in women’s shelters with his mother and brother. During a stay at a domestic abuse shelter, a young Chaney drew a dinosaur and palm tree on the wall.

“I like working with the incarcerated youth because they remind me of my cousins, brothers and friends,” Chaney said. “I never went to juvie, but I understand those kids. And I understand what helped me.”

The previous Art Dojo projects took place in Kennewick and East Pasco, Washington. The Spokane installation is special for its unprecedented means of communication because of COVID-19. Pandemic protocols prohibited the youth from interacting face to face with Chaney, so 1,500 miles away in Arizona and through Zoom, Chaney led the youth and juvenile correction officers Adam Popp, Leo Avila and Cheyenne Conrad through the process.

“The other unique thing about this one, it’s more efficient,” Chaney said. “I know what I’m reaching for, but the first Art Dojo was experimental.” Chaney said the group hit the ground running, starting with a vision board that included four “destinations” from the future: what their home and family life will be like, hobbies they’ll have, work or dreams they’d like to pursue and personal, mental and physical health conditions.

“You stir the imagination a little bit,” Chaney said. “I always ask, if a genie were to pop out the lamp, and you have to immerse yourself into the future, what would the children ask for?”

During each session, the children started with Bugg’d, a mental health check-in with Chaney for every session. One by one, each youth would go around and talk about their “bad and ugly,” then their “good and grateful” and their “dope for the week.” The topics range from family events to what’s happened in court proceedings, even their reality of being in the detention center.

With the Zoom meeting structured with the children as a group, they witnessed their peers’ vulnerability, and it also gave the trio of officers a chance to strengthen their bonds with the youth.

“Starting the group meetings with Bugg’d, I think (you saw the effects) during the projects,” Conrad said. “They were calm and comfortable, and it segued into the conversations we did have during the projects. It’s allowed us to connect since we were there alongside them.”

For the next few weeks, Chaney led weekly sessions to write poems that detail their young life experiences.

These poems hang in the common area where the juvenile center hosts lunch and visitation. Along with the poems, one child practiced an eye filling with tears until they perfected it in another sketch of a stoic woman with chiseled features sobbing and wearing a flower crown.

Within the art, there is a raw willingness to be vulnerable. The children detail some of their trauma – some outright admitting they’re “in their feelings,” others knowing that death is certain, something they’ve known since their father died suddenly.

Whether speaking about the envy of innocence they see in their younger siblings or the day their brother was killed right before their eyes, the incarcerated youths are soothing themselves, using poetry as a means to heal from the life that’s led them into incarceration. Instead of asking “What did I do to end up where?” the children center themselves in their trauma, asking the tough, inward question of “What happened to me?”

“We talk cancel culture in America, but these incarcerated youth get canceled in the system. We need to create cultural compassion and restorative justice, especially with our youth with these programs,” Chaney said. “Some of the kids I work with, you see the turnaround and you see the connection and (when we help) these children.”

After the poetry sessions, the kids moved on to paint a mural with one word in a hallway. Aligned with their vision boards, they agreed on the word “dream.” The word covers the entire wall with 16 handprints of the 13 youths and three officers. The mural creation soon took a backseat once detention staff recognized the children’s ability to put aside their differences.

“We had rival gang members standing next to one another saying, ‘That’s really cool how you painted that,’ and that’s what this project is about,” Avila said. “Watching these kids work together, assigning each other certain roles that complemented their natural abilities was so special to us.”

The children then took the art therapy into their own hands by hosting their first poetry slam with pieces written during their e-time with Chaney. The juvenile officers were blown away by the extra steps the children took, having to limit the poetry performances to just one entry after the children flooded the submission process. The kids still meet on Tuesdays. Bugg’d is still a way the kids and officers break the ice.

“The fact that our staff want to continue it shows it’s been a valuable tool for them to understand what’s going on in the kids’ life at that point in time and adjust and best help where those needs are,” Marshall said. “They got to bond with one another over this project, they got to one another through sharing poetry and what they have in common. I think that gelled them. They’re a team now.”

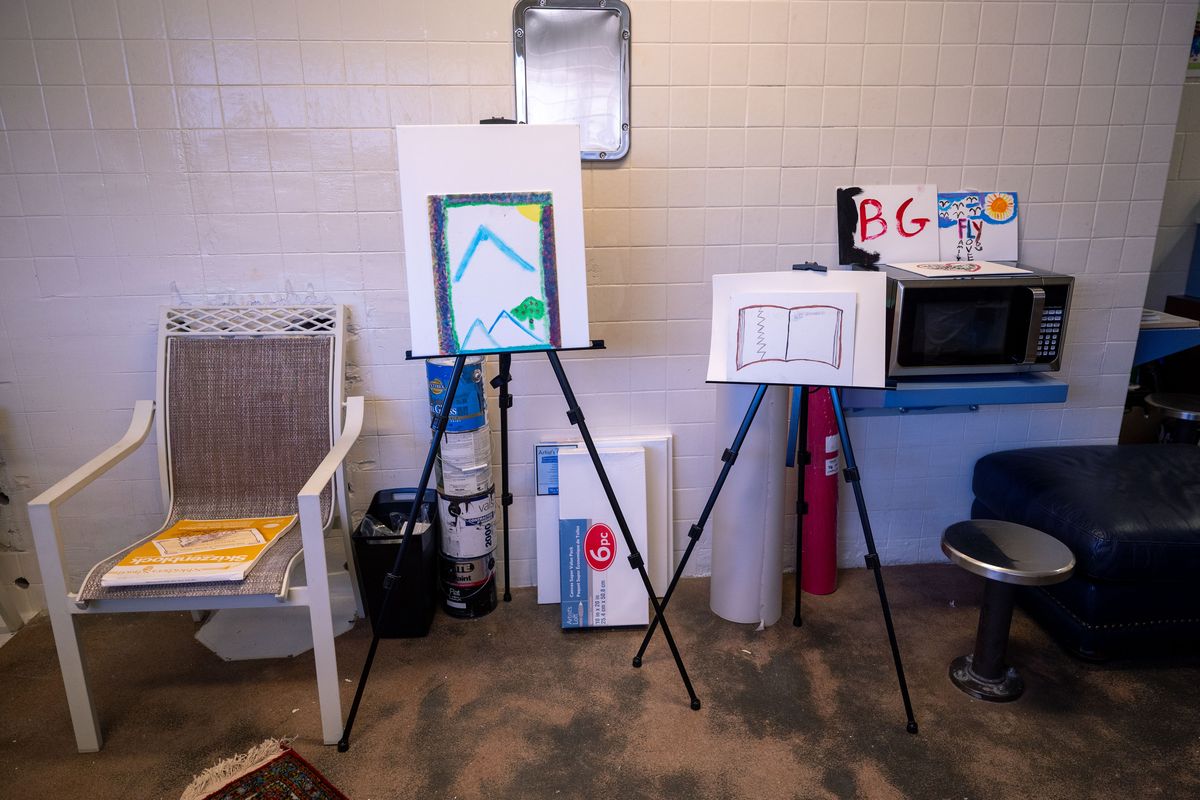

Art Dojo is up and running. After being inspired by the children, the Westminster Congregational United Church of Christ donated items for Art Dojo. It is set up with bean bags, paint utensils and other art supplies.

Marshall wants the children to create more art on the detention center’s bare walls and is working with Spokane artists to create more art mediums like jewelry or sculpting to include in future à la Art Dojo projects. For Chaney, he hopes Art Dojo encourages children to tap into their talents so they “look at themselves and their potential differently.”

“The way we talk about the public-school-to-prison pipeline, these projects are court-to-community pipelines,” Chaney said. “We presented this, and we want to present (Art Dojo) on a state level as part of the racial justice conversation right now. It’s little efforts like this that help me creatively dismantle these systems and change them.”