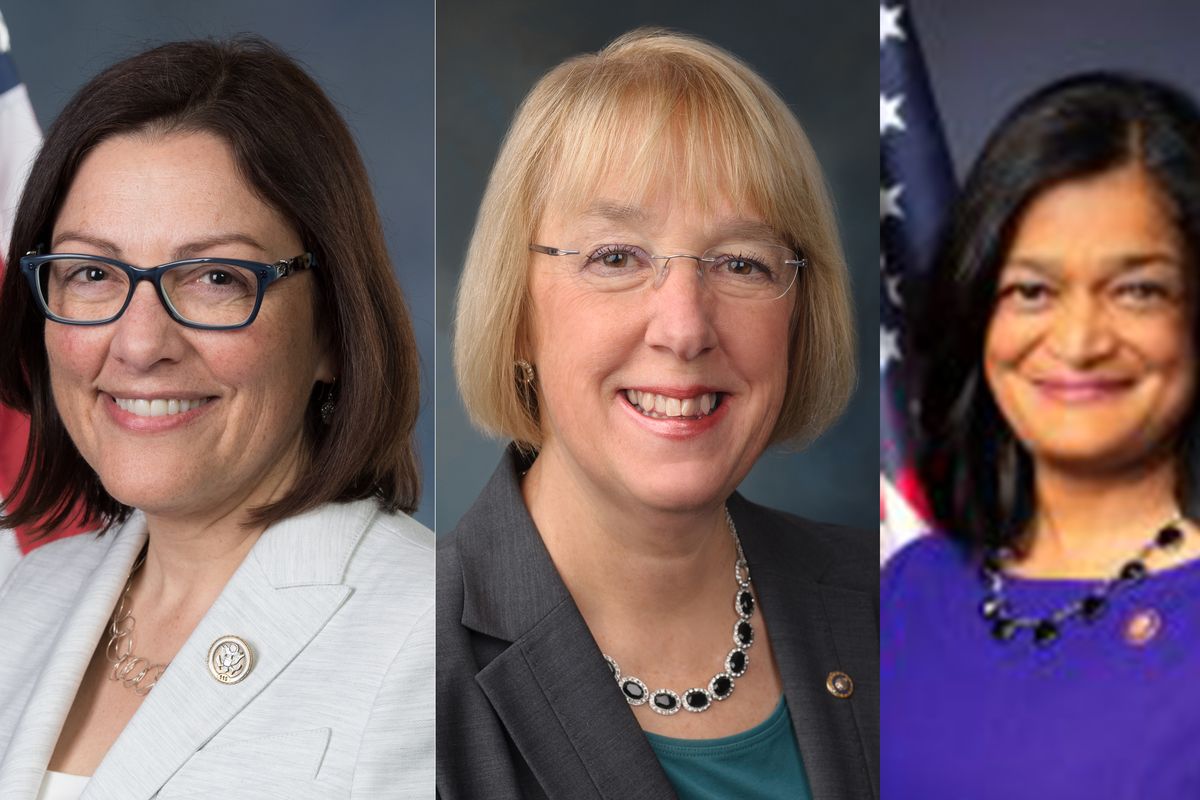

Three Washington Democrats at center of crafting bill to ‘fundamentally reshape the American economy’

WASHINGTON – Three Washington lawmakers are at the center of a debate among Democrats that will decide the fate of the ambitious national agenda they campaigned on in 2020 – and perhaps the party’s fortunes in 2022.

Sen. Patty Murray played a central role in crafting the Build Back Better Act, which would raise taxes on large companies and the richest Americans to pay for a range of social programs aimed at lowering living costs for the rest of the country, including expanded health care, subsidized child care and tuition-free community college.

“It’s going to be a really big deal,” Murray said in an interview. “We’re going to fundamentally reshape the American economy so we can level the playing field for working families, and we can do it by making sure that the very wealthiest and giant corporations pay their fair share, so that everyone can be successful.”

But before they can do that, Democrats have to pare the legislation down from a cost of $3.5 trillion to a figure closer to $2 trillion to appease two centrist senators.

That reality presents them with a tough choice: fund all the programs they promised voters, but for just a few years, or jettison parts of the bill to fund their top priorities for the longer term.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who represents most of Seattle and chairs the Congressional Progressive Caucus, has pushed for the first option. In an interview, she said that because the bill’s provisions aim to help different groups of people – expanding Medicare coverage for seniors, for instance, and cutting costs for college students – dropping entire programs would mean breaking promises made to voters.

Rep. Suzan DelBene, whose district stretches from the Seattle suburbs to the Canadian border, heads the moderate New Democrat Coalition and has advocated the “fewer, longer” approach. If Republicans take control of either the House or Senate next year, she said in an interview, they could let programs with only short-term funding expire before they see their full impact.

The Progressive Caucus and New Democrats each count 95 members in the House, evenly splitting most of the party’s slim, 220-seat majority. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., has struggled to take a side.

After writing in a letter to all House Democrats on Monday that her members have “overwhelmingly” advised her “to do fewer things well so that we can still have a transformative impact,” Pelosi told reporters the next day her party may have to opt for short-term funding and she hoped they wouldn’t drop any provisions.

After a late-September standoff between progressives and centrist Democrats forced Pelosi to postpone a vote on the Build Back Better Act, the speaker set an Oct. 31 deadline to vote on both that legislation and the bipartisan infrastructure package the Senate passed in August.

But Murray, the third-ranking Democrat in the upper chamber, shrugged that deadline off as “a House-imposed mandate” and said she’s focused on getting “the best package possible, with the strongest investments in the things that I care about.”

The challenge Murray, Pelosi and other Democratic leaders face is that each member of their party cares about different priorities.

After Biden presented his sweeping agenda in two sets of proposals last spring – the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan – lawmakers turned them into two bills. But instead of dividing the issues like the White House did, a group of moderate Democratic and Republican senators carved out provisions that could garner the 10 GOP votes needed to reach the 60-vote majority needed to pass most legislation in the Senate.

That bipartisan bill passed the Senate – including $550 billion in new spending on roads, bridges and other infrastructure – and with just one shot at bypassing a Senate GOP filibuster via special budget rules, Democrats piled the rest of Biden’s agenda into the Build Back Better Act.

All 50 Democratic senators need to support a bill to use that once-a-year process, known as budget reconciliation, and opposition to the original $3.5 trillion price tag from Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia has forced the party to compromise on a lower number.

In its original form, the sprawling bill would provide two years of free community college, plus extra college funding through the Pell Grant program. It would guarantee universal pre-kindergarten and subsidies that ensure no family spends more than 7% of their income on child care. It would expand Medicare to cover hearing, vision and dental care and expand Medicaid coverage in states that haven’t already done so under the Affordable Care Act.

It would extend the monthly child tax credit payments of $250 to $300 per child, set to expire at the end of the year, that Democrats enacted through the $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package they passed in March. It would lower prescription drug prices, partly by letting Medicare negotiate prices for the first time, and guarantee 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave each year.

Other parts of the bill aim to combat climate change, including tax incentives to encourage clean energy production and electric vehicle adoption. The sheer number of provisions has posed a messaging challenge for Democrats: How do they explain it, let alone drum up public support for such a wide-ranging piece of legislation?

Murray, who chairs the Senate committee charged with health, education and labor issues, said her must-have priorities are affordable child care, paid family leave, lower health care costs and provisions to counter climate change.

“Of course, everyone is advocating for what they feel strongest about now,” Murray said, but she emphasized that none of that matters unless they craft a bill all 50 Senate Democrats will vote for.

The New Democrat Coalition has its own four-part set of priorities: Extend the child tax credit, create jobs through economic development grants, “go big on climate” by cutting carbon emissions, and lower health care costs by expanding Medicaid to cover more people and making health insurance subsidies enacted in the March relief bill permanent.

The Progressive Caucus has put forward a broader set of priorities, including investing in affordable housing and the care economy, combating climate change and lowering drug prices, using the money Medicare saves to expand health care.

The progressives have also sought to include sweeping immigration reform in the bill, but the Senate parliamentarian – a sort of congressional referee – ruled that those changes fall outside the scope of the reconciliation process, which applies only to budget-related provisions.

Democrats have proposed paying for the new spending by rolling back some of the tax cuts Republicans passed in 2017, when the GOP used the same budget reconciliation process to get around Democratic opposition.

Their plan would raise the corporate tax rate from 21% to 26%, still below the 35% rate that applied until 2018, with lower rates for businesses that earn less than $10 million a year. It would tax capital gains at a higher rate, especially for people who earn more than $5 million a year, and raise the income tax rate for those making at least $400,000 a year.

Those proposals would generate about $2 trillion in revenue over 10 years, which means if the Democrats choose to fund programs for just a few years, they would need to find other ways to raise revenue – or finance the programs with borrowed money that raises the federal deficit – but Jayapal said she’s not worried about finding ways to pay for the programs.

“We don’t suffer from a lack of resources on the revenue side,” she said. “We suffer from a lack of will to actually tax people fairly.”

The other downside to short-term funding, DelBene said, is that if Republicans win control of either the House or Senate in 2022 – a scenario polling and precedent suggest is likely – Democrats could be forced to watch parts of their bill expire before they have their full impact, “leaving a program halfway done.”

“I think folks want to see governance work,” DelBene said. “They want to see us make decisions and have policy that is stable, that they can rely on.”

To make her point, DelBene cited the child tax credit, which she played a lead role in transforming from a $2,000-per-child benefit – available only to those who earn enough to owe that much in federal taxes – into monthly payments totaling $3,000 to $3,600 a year for all but the wealthiest parents. A Columbia University study found the first round of payments, sent in July, lifted 3 million children out of poverty, but projected a far greater impact if the payments continue for years.

Meanwhile, Jayapal favors front-loading as many benefits as possible, in hopes that “people will understand that government has their back, and we can look at the extension of those programs later.”

“One of the crises of democracy that we’re facing is that people don’t believe that government is going to stand up for them,” she said. “The way to counter that is to show them that government really can do those things, and so we’re building towards a place where voters actually see the utility of government.”

While she admitted her approach could let Republicans dismantle her priorities in a few years, Jayapal said she hoped the GOP would run into the same problem they faced when they tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act, a program that proved too popular to undo once Americans saw its benefits.

If Democrats don’t do all the things the party campaigned on, Jayapal said, “Then people are going to continue to have no faith in us because we promised something (and) we never delivered. They gave us the House, the Senate and the White House, we still didn’t deliver.”

Despite their different approaches, Jayapal, DelBene and Murray described the same goal: a federal government that more actively transfers wealth from the biggest businesses and the richest Americans to make life easier for the rest of the nation.

“I want people to wake up in the morning and feel differently about their lives, their livelihoods and their opportunities,” Jayapal said. “I mean, to know that government’s got their back and they can live a dignified life with opportunity and not suffer every day.”