We the People: Voters didn’t always elect U.S. senators

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Who elects U.S. senators?

Senators are elected to six-year terms in statewide elections by the voters in the states they serve. But that was not always the case.

When the U.S. Constitution was written in 1787, the Founders required members of the U.S. House of Representatives to be chosen by voters, but senators were to be appointed by state legislatures.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention had been appointed by their state’s legislatures, which established the precedent for that method for choosing senators, the Senate Historical Office says on its website.

“The framers believed that in electing senators, state legislatures would cement their tie with the national government, which would increase the chances for ratifying the Constitution,” which was up to the legislatures, the office notes. “They also expected that senators elected by state legislatures would be able to concentrate on the business at hand without pressure from the populace.”

But legislatures were not immune to political pressures. By the middle of the 19th century, the conflict over slavery resulted in party splits that kept some states from settling on a senator and having the seat being vacant for years. After the Civil War, problems continued, and even though Congress passed a law in 1866 regulating how state legislatures were to elect senators, some states deadlocked on their selections and allegations of intimidation and bribery were common.

One provision of the law required legislatures to take daily votes on electing a U.S. senator after they’d been in session for at least 10 days.

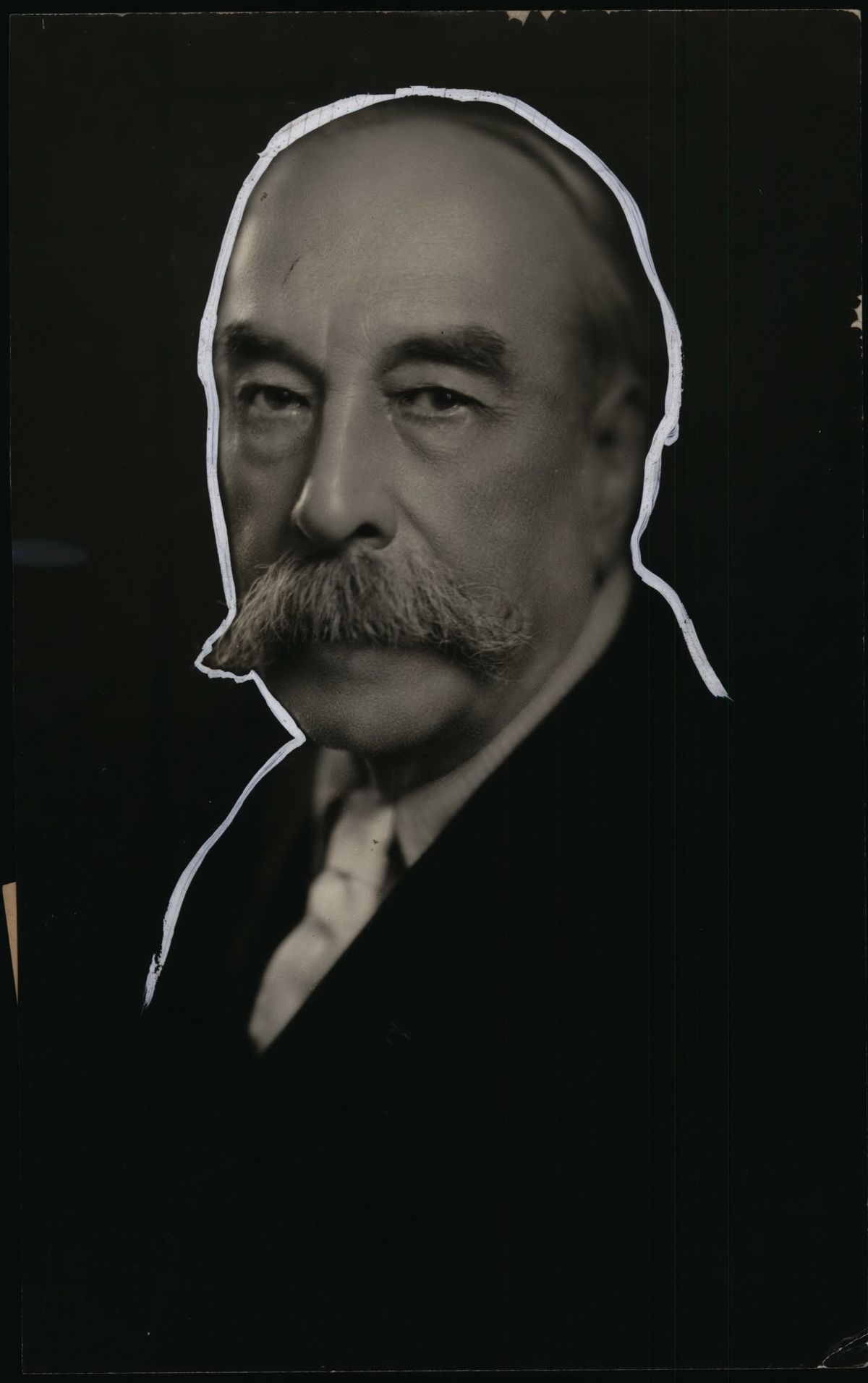

The Washington Legislature struggled at times electing U.S. senators in the years after statehood as its political makeup shifted. The 1890 Legislature, the first after Washington became a state in November 1899, was overwhelmingly Republican and easily selected a former governor, Watson Squire, and a former U.S. House delegate, John B. Allen, as the state’s first senators.

Squire faced re-election in 1891, and even though Republicans still held sizable majorities in both chambers of the Legislature, the rivalry between Seattle and Tacoma split votes between Squire and W.H. Calkins of Pierce County. Daily votes happened for more than a week without a winner. There were allegations of bribery, including a claim by one Stevens County legislator that he’d been offered $500 for his vote. Historian Don Brazier described a “near riot” in the street in front of an Olympia hotel that was serving as the headquarters for both candidates when Squire supporters claimed they had the necessary votes.

“The near riot continued in the lobby and spilled out into the street but the battle was over and at a joint session the following day, Watson Squire was elected to a six-year term in the U.S. Senate,” Brazier wrote in the “History of the Washington Legislature, 1854 to 1963.”

Two years later, the Legislature deadlocked over whether to re-elect Allen to the Senate. Even though Republicans still controlled the Legislature, Allen continued to fall a few votes shy of the needed majority over the course of some 100 ballots. When the Legislature adjourned without electing a senator, fellow Republican Gov. John McGraw appointed Allen to the seat. But the U.S. Senate, controlled by Democrats, refused to seat any senator who was appointed rather than elected by their state legislature and one of Washington’s two seats went vacant for two years. In 1895, the Legislature spent a month of daily votes before selecting John Wilson of Spokane over Allen and a third candidate.

In 1897, a coalition of Populists, Democrats and Silver Republicans – so named because they split from other Republicans by supporting silver as well as gold as a backing the nation’s monetary policy – managed to put together the votes to replace Squire with George Turner, a Spokane-area judge, after several days of votes.

Two years later, Wilson couldn’t get the support needed to be re-elected and in a three-way contest eventually threw his support to Addison Foster, but not before the process consumed most of January, Brazier wrote.

After the turn of the century, Populists and Progressives around the nation began a push for a different way of selecting senators, aided by journalistic accounts of bribery and vote-buying. Oregon and Nebraska passed laws that allowed their voters to pick their state’s senators. By 1912, more than half the states – including Idaho but not Washington – had a system for popular election of senators. That year, a constitutional amendment for all states to have their voters elect senators passed both houses of Congress with the necessary two-thirds super majorities after some contentious debates.

The 17th Amendment was ratified in less than a year, in April 1913, and went into effect for the Senate elections in 1914. It makes a minor change in Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution, replacing the phrase “chosen by the Legislature thereof” with “elected by the people thereof.” But it’s a major change in the nation’s political structure that gives more direct power to voters.

Some conservatives have suggested the change should be reversed. The Utah State Senate, which didn’t ratify the amendment in 1913, passed a resolution calling for its repeal.

In Washington, State Sen. Val Stevens, R-Arlington, introduced resolutions in 2009 and 2011, calling on Congress to reamend the Constitution and return to the old way of electing U.S. senators. Neither proposal collected any co-sponsors and never received a hearing or a vote and there is no concerted effort to shift the power back from voters to their state legislatures.