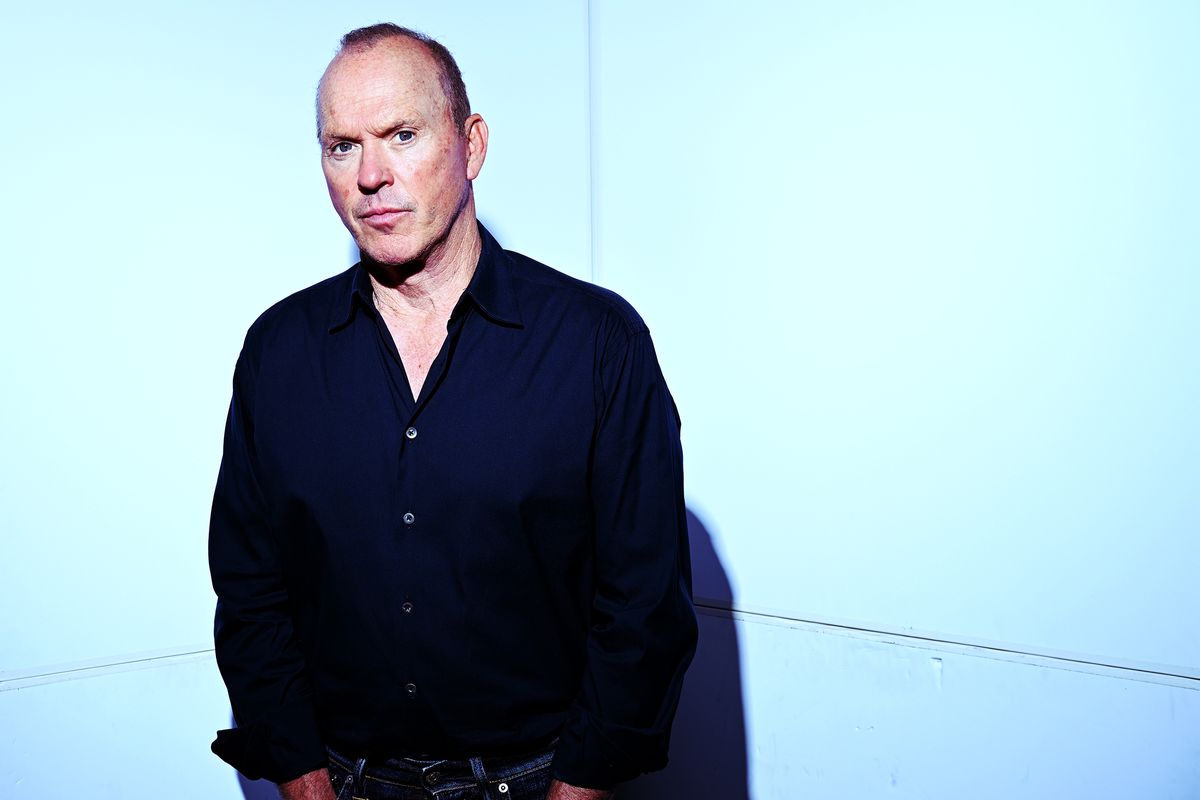

Michael Keaton was scared to take on his latest role, in ‘Dopesick,’ and that’s why he did

Asked why he offered Michael Keaton a lead role in his new Hulu miniseries, “Dopesick,” creator Danny Strong responds as you might expect: Why not? He shot for the stars – well, one star in particular – and figured that if he were to rack up a few passes, he might as well get the first from Keaton.

But Keaton didn’t pass on the opportunity to play Samuel Finnix, a fictional doctor in a Virginia mining town plagued by the onset of the opioid epidemic – and one of several characters carrying viewers through a multitimeline tale of how OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma gained significant footholds in similar towns and cities nationwide. Keaton’s reason for signing on isn’t too complex: The story, which also tracks federal prosecutors’ dogged investigation into the company, was just that compelling.

“Dopesick” arrives a matter of weeks after a bankruptcy judge approved a settlement plan that, while costing Purdue Pharma’s former owners roughly $4.3 billion, also granted them substantial legal immunity. (The appeals are “mounting,” according to the Associated Press.) The series takes aim at the Sacklers and presents a narrative that hinges upon viewers’ sympathy for people like Finnix, a man essentially duped into prescribing opioids by a pharmaceutical rep. What a relief it was for Strong to have landed “everyone’s favorite actor.”

In early October, the two men sit across from each other in a hotel suite overlooking Lafayette Square and, past that, the White House. Keaton squirms a little while listening to Strong’s praise, attributing his discomfort to having been raised Catholic (“I didn’t even do anything, and I feel guilty,” he says). But he agrees with Strong’s assessment of the doctor. Finnix, per Keaton, is a “mensch of mensches.”

Though fictionalized, the role fits with others Keaton has taken on in a phase of his career touching on several of these resonant, often-political real-life stories, whether the Boston Globe’s investigation into the local Catholic archdiocese in “Spotlight” or, more recently, a lawyer’s efforts to empathetically allocate compensation funds to the loved ones of 9/11 victims in “Worth.”

Keaton says he doesn’t necessarily need to like the characters he plays but instead looks for a quality in them that he hasn’t explored before. A self-described two-newspapers-a-day guy – sometimes 2½ if you count the sports section of the New York Post – he’s driven by innate curiosity and his ability as an actor to learn by treading unfamiliar ground in newly adopted pairs of shoes. “Who wouldn’t want that challenge?” he says. “If I’m a little frightened, that’s usually a good thing.”

“Dopesick,” a mashup of the words used to describe opioid withdrawal symptoms, shares its name with a 2018 book by Beth Macy, a journalist who traced the continuing crisis back to the release of OxyContin in 1996. Purdue Pharma said at the time the pills were less addictive than other available opioids – that OxyContin’s extended-release method meant fewer than 1% of prescribed patients would get hooked, as ambitious sales rep Billy Cutler (Will Poulter) parrots to Finnix in the series.

Such a statement seems ludicrous now; nearly half a million people have died of opioid overdoses since the late 1990s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After producer John Goldwyn reached out to see whether Strong would be interested in writing about the issue and its relation to the Sackler family, which owned Purdue Pharma, Strong began to research them and says he was “blown away” by the “extent of their lies, deceit, influence peddling and the fact that this entire crisis stemmed from one company.”

“I just thought people need to know what happened,” he adds. Using Macy’s book as a compass, Keaton, Strong and fellow executive producer Barry Levinson, who directed some of the show, envisioned a backstory for Finnix: He followed the love of his life to Appalachia, and then fell for the region and its inhabitants, as well.

“Dopesick” has received mixed reviews, but Strong’s efforts to stoke anger undeniably benefit from the humanity on display. He depicts Finnix and his patients – such as Betsy (Kaitlyn Dever), a young woman prescribed OxyContin after a mining accident – as having been preyed upon by a company looking out only for its profit margin. The story of insidious capitalism is as American as it gets, the resulting indignation harnessed in the series by federal prosecutors (Peter Sarsgaard and John Hoogenakker) who team up with a DEA agent (Rosario Dawson) to expose Purdue Pharma.

“In 2007, (the company) pleaded guilty to a statement of facts that has disappeared to history, that is so damning and so outrageous,” Strong says. “The fact that there were these prosecutors onto them … I thought, well, this could be an exciting piece of muckraking, but there’s kind of a thriller here, too.”

Though the Sackler name appears on numerous cultural institutions – including a Smithsonian gallery about 1½ miles from where Keaton and Strong sit – the Sacklers themselves tend to avoid the public eye. They have denied responsibility for the opioid crisis; in an internal Purdue Pharma email from 2001 that Massachusetts state prosecutors cited in an early 2019 lawsuit, then-company president Richard Sackler instead blamed the unfolding crisis on “the abusers.” “They are the culprits and the problem,” he wrote. “They are reckless criminals.”

Soon after the Massachusetts complaint was made public, “Last Week Tonight” host John Oliver said on his show that when it comes to Sackler, a key figure in developing OxyContin, “invisibility feels deliberate.” To underscore just how “malicious and coldhearted” Sackler’s emailed words were, Oliver recruited a handful of actors to recite them – including Keaton, because, as Oliver put it, “when you’re casting for a shadowy heir to a vast fortune who doesn’t like to be in the limelight, you go Batman.”

Whether reciting an executive’s sinister writing or giving an unassuming performance in “Dopesick,” Keaton always mines for his characters’ motivations: What makes them tick? In contrast with the series’ supervillain-esque portrayal of Sackler (Michael Stuhlbarg), Keaton lends a studied gravitas to Finnix. The doctor isn’t a hero, per se, but he has an honorable quality the actor plays up to a believable extent.

Which makes it all the more devastating to witness the character grapple with his culpability in the issue at hand – is it his fault for believing what he was told about OxyContin? Even when the series gravitates toward more black-and-white storytelling, Keaton makes a point to search for the gray. “It’s just a challenge to see if you can pull it off,” he says.

The actor seeks nuance. Toward the end of “Spotlight,” as the Globe exposé nears publication, Keaton’s character, the editor Walter Robinson, reveals he had received a list of sexual abuse allegations against priests years before but never acted on the tip. His character in “Worth,” attorney Kenneth Feinberg, is initially seen as insensitive for developing a rigid formula to estimate the value of human life. With “The Founder,” about former McDonald’s chief executive Ray Kroc, Keaton says it was a “prerequisite” that the film not turn out to be one “where at the end you go, ‘Well, he’s wonderful.’ “

The hope, he continues, is that “Dopesick” can send a message without being “preachy and pretentious.” “If it all blows up tomorrow, and I’m not (acting) anymore because nobody really cares about me doing that anymore, which is always a possibility,” he says, “then I go well, you know, I have something out there in the world that maybe did something and helped someone. So that’s where this ranks.”