The tragic story of Dan Grayson: Questions continue to swirl around the death of former Washington State linebacker

The pregame clock would be ticking down, and inside the Washington State locker room Dan Grayson would make the rounds.

“He’d walk up to you,” remembered teammate John Husby, “and his eyes were like two blowtorches. They were just alive, and they would draw you in.”

And then he’d deliver his message, simple and direct. Nothing necessarily more original than any being imparted in other locker rooms across the country on a college football Saturday, but with an urgency made irresistible by those eyes.

Play today like it’s your last game. Play every play like it’s your last.

“Dan came from tough, humble beginnings and didn’t have the easiest of lives growing up,” Husby said. “But he had an opportunity and he knew it, and he was going to make the most of it. He understood that things can be taken away. He understood the finality of things.”

Now, too, do his family and his friends. They’d like to relay the message for him.

• • •

Four weeks after burying her husband of nearly 30 years, Tina Harding steeled herself and walked into Martin Stadium for Washington State’s game against USC.

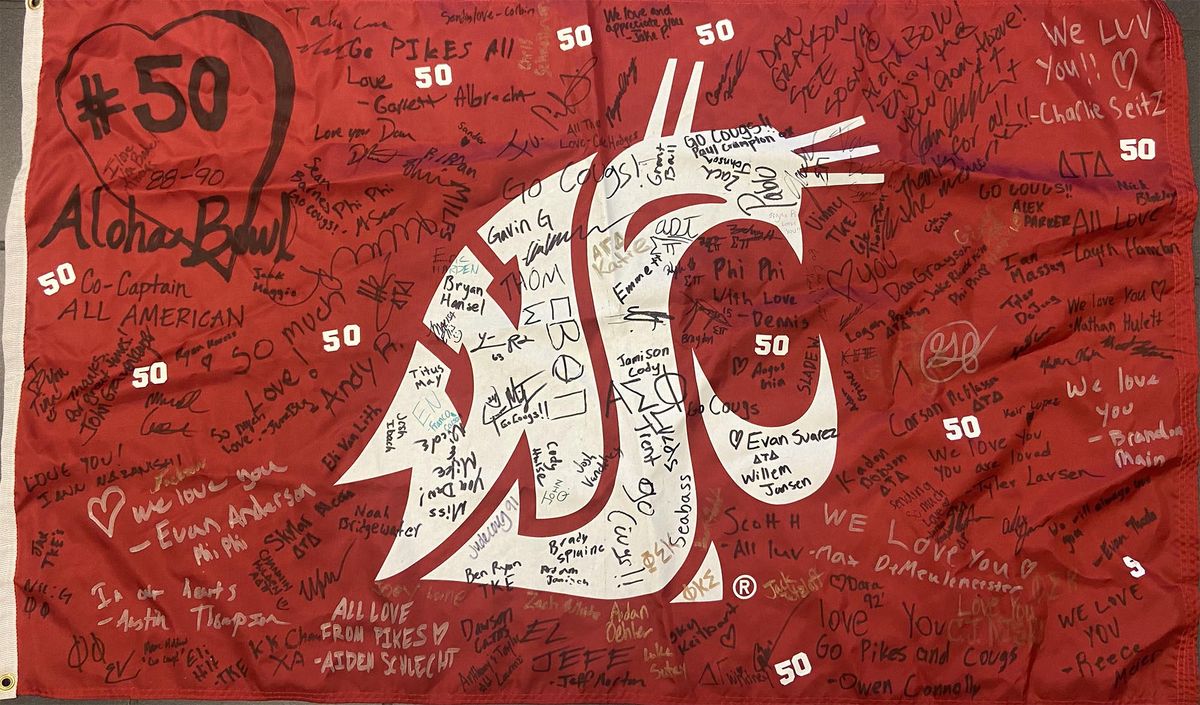

With her was John Gravenkemper, a friend dating back to college days, the self-described “social chairman” of a group that orbited around Grayson and some Cougs of the late 1980s – Husby, Tim Stallworth, Tim Downing, Tony Savage, Randy Gray and others. And together they handed out 1,500 eye patches with Grayson’s old number “50” on them while telling the story.

Eye patches?

“It’s a way for people to see what it’s like to have a brain injury,” said Gravenkemper, who nearly died of a brain tumor that went undiagnosed for years and must wear his patch daily.

And the story?

That Dan Grayson died at the age of 54, a once-good life lost to pain and dysfunction and chaos that left his family broken and Grayson’s spirit unrecognizable before a tragic, ugly end.

“And what he died of,” Harding said, “was brain injury, whatever it says on the death certificate.”

It isn’t just Grayson. Three other former Cougs in their 40s and early 50s – Dorian Boose, Vince Saldivar and Gary Holmes – have died in the past five years, all at least suspected to have suffered from traumatic brain injuries that contributed to behaviors or disorders that led to their deaths.

By coincidence, this happens to be Pac-12 Mental Health Week, and at WSU they’ve been engaged in events daily to support training and hear stories of athletes’ struggles with depression or other issues. One of the partners is Hilinski’s Hope, the mental health advocacy foundation started by the parents of former Cougars quarterback Tyler Hilinski, whose 2018 suicide rocked the campus and triggered much-needed conversations nationwide about pressures on college athletes and students.

But, of course, it’s an issue beyond college.

“You wonder where’s the support when these guys are 40, 45,” Gravenkemper said. “There are guys dying alone, and families that have had to live with this for 20 or 30 years.”

So on Saturday when ESPN’s College GameDay stops in Dallas – where Gravenkemper lives – and the Ol’ Crimson flag is hoisted in camera range for the 264th consecutive show, it should be adorned with the number 50, which Grayson wore in 1988 and ’89.

In hopes of getting another conversation jump-started.

• • •

So here it is: Dan Grayson died in the early hours of Aug. 1, in the parking lot of a Quality Inn in Kennewick, where he lived. The circumstances are mysterious – police have ruled out homicide, but continue to investigate. The autopsy called it a “medical event (after) other activities.” Harding acknowledged that there were “substances” in his system, without elaboration.

“This is what happened to him,” she said. “It wasn’t who he was.”

It’s not denial. Harding is clear-eyed and frank about the behaviors she witnessed and experienced in Grayson’s spiral, that led her to obtain protection orders and finally a divorce in 2019, secreting herself out of town for her own safety. She speaks of irrational, volatile episodes that led to her children’s estrangement from a father who once doted on them and coached them in youth sports.

“This is a hateful disease,” she said, “and you hate those behaviors. But I want to remember the man I love and respect.”

That would be the man she met at the old Rathaus Pizza in Pullman when they were both students, who noticed they had the same bracelet “and wouldn’t leave me alone,” she laughed.

Grayson’s was a remarkable – and tragic – story even then. He showed up at WSU in 1987, his belongings in a garbage bag, as a football walk-on from Wenatchee Valley College, where he’d played wingback. He’d grown up in logging country in Woodland, Washington, in an alcoholic family (“the cops used to be at our house every weekend,” he said back then) and after his mom got a divorce when Grayson went off to WVC, she was killed by a drunk driver.

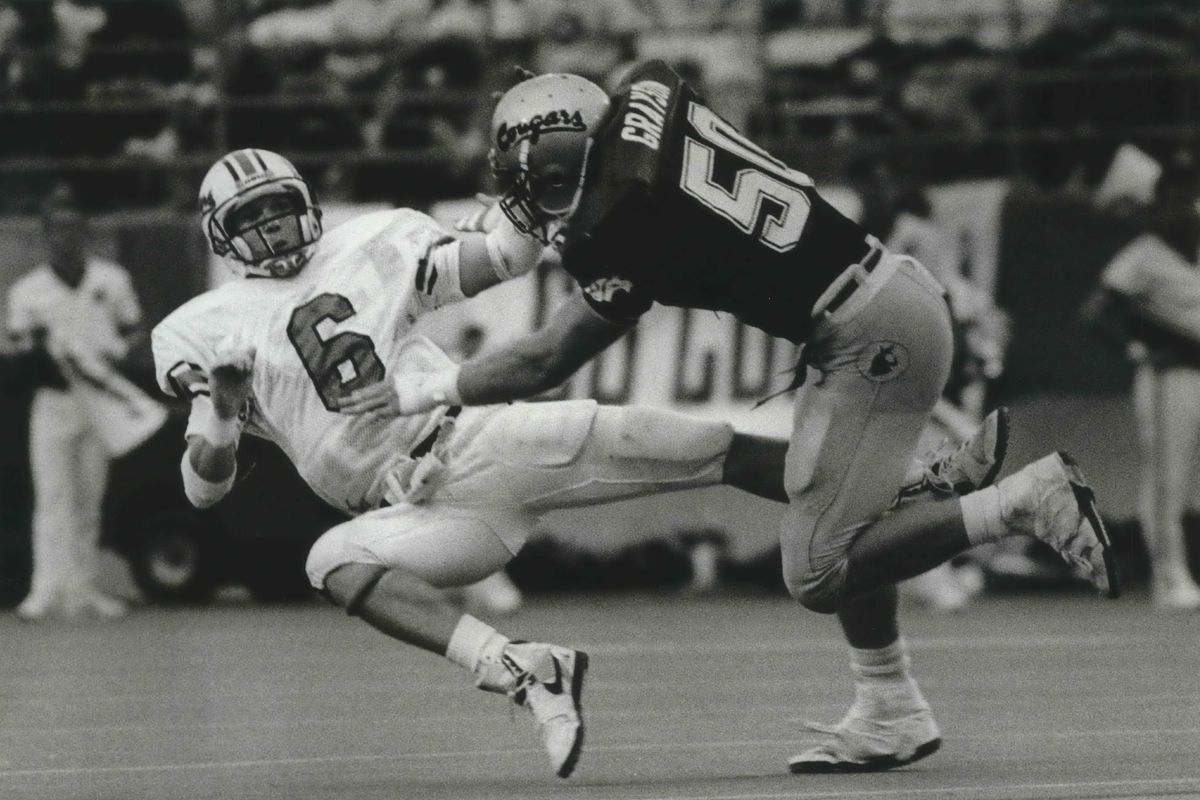

But he was not the average walk-on. He was 240 pounds, ran a 4.5-second 40-yard dash, had a 35-inch vertical leap and squatted 660 pounds. A spectacular forced fumble in a spring scrimmage prompted Dennis Erickson stop play and shout, “Grayson! I’ll tell you what, you’re on scholarship right now!” – theatrics usually not in the coach’s repertoire, but which spoke to every player on the team.

By 1988, Grayson was WSU’s starter at middle linebacker on the team that beat No. 1 UCLA en route to the Aloha Bowl, and he was All-Pac-10 in ’89 – and a seventh-round NFL draft pick by the Steelers.

Pro football did not work out. Neither did a stint as a farmer (“He was afraid of pigs,” Harding confessed). But he settled into the financial industry until 2002, when he took a job with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland.

“You know, he was always just a big goofball,” Harding said, “happy and laughing. He was that way in college and after, and he loved his kids. He’d had a bad shake at life early, but he made the best of it. But there was always some kind of thing he had to overcome.”

It was about 10 years ago that she began to notice changes – more anxiety, impulsive behavior and mood swings, increased physical pain, memory loss, depression. Doctors were consulted, and Harding even got certified in yoga to try and help him cope.

“When the ‘Concussion’ movie came out, there was that scene in which Justin Strzelczyk takes his truck into the gas tanker,” she recalled. “He was actually Dan’s roommate with the Steelers, which was frightening enough. I said, ‘I can’t watch this.’ I was recognizing a lot of stuff.

“It’s a slow bleed or like picking a scab. There’ll be a huge blowup, then you’ll slowly heal, then another anxious thing.”

And then an acceleration out of control.

“I remember one person saying, ‘Just hold on,’ ” she said. “But you can’t hold on to the unknown.”

• • •

Inevitably, after each instance of a football player’s death in which traumatic brain injury or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is suspected as a cause or trigger, the choice to even engage in a sport with such a potential for great harm – and not just to the players – comes into question.

Husby is as thoughtful a source to speak to that as there is.

“I’m asked all the time,” he said, “and it’s yes, I’d do it again. Yes, a hundred times. A thousand. I just had knee surgery, I have 85-year-old elbows, my hips and ankles are falling apart. But it’s the yin and the yang. It’s still a great sport and to have played it, with the relationships you forge and experiences you have, you’d do it again. But there has to be awareness and people now understand a brain injury isn’t like a bruise to the arm. There are lasting effects, and your life has to be monitored. And measures are being taken to make the game safer.”

Even Harding said, “I wouldn’t change it. I have my children, and I had a soulmate. I wish I could have the happily ever after, but you grieve what you don’t get it.”

When NFL Hall of Famer Junior Seau committed suicide in 2012 and tests at the National Institute of Health revealed evidence of CTE, Grayson had a moment of clarity.

“This was out of the blue one day,” Harding said. “He said, ‘I want to donate my brain so they can do studies on it.’ ”

So last month, Grayson’s brain was sent off to the NIH and in eight or nine months when the testing is completed, Harding and her children will sit down with doctors at the University of Washington to discuss the findings, and try to reconcile the science with what happened in their lives.

In the meantime, maybe an eye patch, a flag and a number can shine a little more light.