What could you eat 500 years ago in the Pacific Northwest?

Today it’s all about Cosmic Crisp apples, winter wheat and wine grapes, but 400 years ago Washington state’s food environment looked a lot different.

The mechanized system of food production has churned over recent centuries, but when the land was occupied only by Indigenous people whose ties to the land had deep roots, the Pacific Northwest served an abundance of helpful herbs, fragrant flowers, fat-rich fish and vital vegetables that could easily make a feast.

So don’t worry about whether you’d be able to have your modern fall feast back in the 17th-century Pacific Northwest. What was available is delicious.

Protein

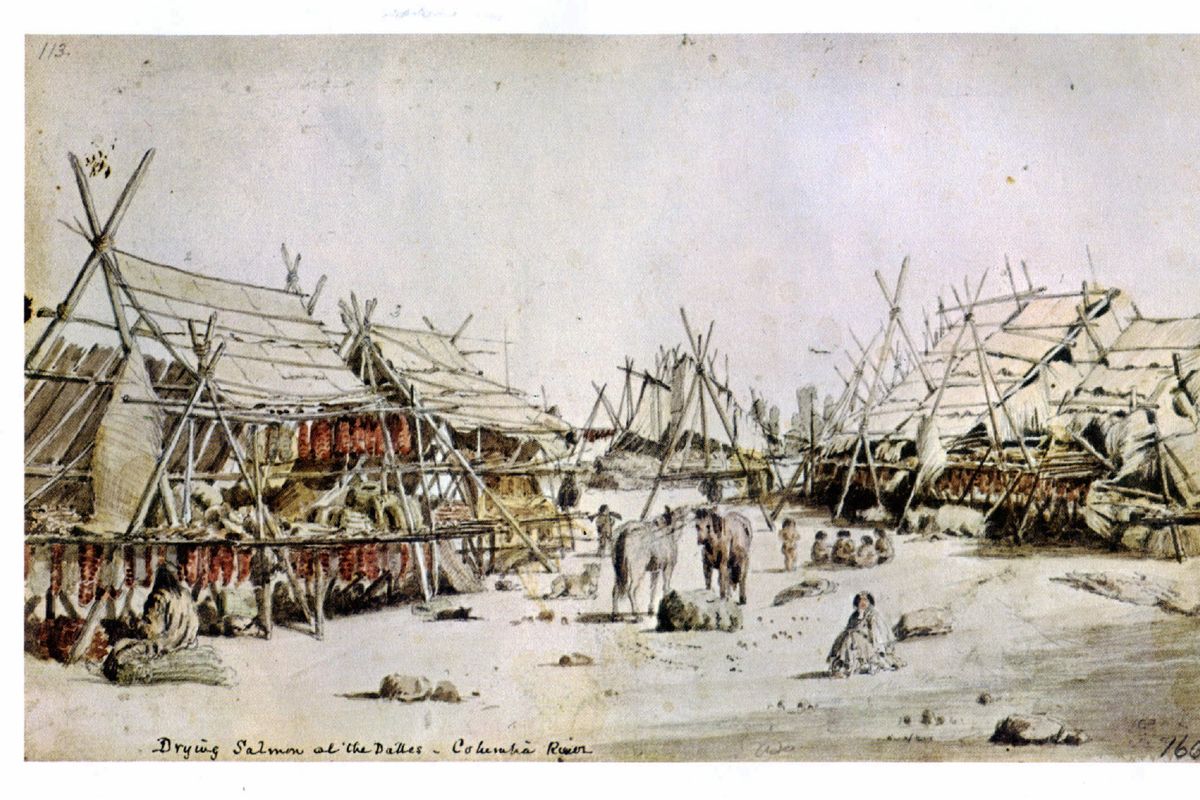

Salmon is considered a “First Food” for Indigenous communities of the Upper Columbia River tribes – Coeur d’Alene, Kalispel, Kootenai and Spokane, according to a report from the First Nations Health Authority, an agency in British Columbia focused on improving wellness in Indigenous communities.

Tribe members would sometimes make the long trek to the plains to hunt buffalo, but salmon is widely known as the protein of choice for communities in the Inland Northwest.

Salmonid species in the Columbia and Spokane rivers, such as Chinook, sockeye and steelhead, were commonly caught and then cooked, according to the Spokane Tribe of Indians website. Cooks sometimes drove a wooden stake through the body of a freshly skinned salmon, and then cooked it at an angle over a campfire.

Other fish like sturgeon, lamprey eels, suckers and various species of traits also helped sustain these communities. Diets for people in the Northwest also included a fat-rich fish called eulachon found in the rivers, Washington State University anthropology researcher Shannon Tushingham told WSU Insider earlier this year.

Researchers estimate these four tribes harvested 6.8 million pounds of salmon each year, according to the Spokane Tribe of Indians. They also sometimes hunted and ate elk and deer when it was cold because the animals provided warm hides in addition to their meat.

Many Native American tribes used stone and pottery for cookware until later centuries, according to a 2016 article on Native American food history in the Journal of Ethnic Foods. Salmon could easily be dried, cured and stored to last the winter.

Vegetables and starch

Washington state today leads the nation in producing apples, cherries, blueberries, hops and pears, according to the state Department of Agriculture. Apricots, asparagus, grapes, potatoes and raspberries are also big crops in which the state lands in second place.

In precolonial 17th century the region looked a lot like it does today. Several thousand years prior, at the end of the Pleistocene era, mastodons – large tusked elephants – and camels (yes, according to researchers, a type of camels roamed the PNW Northwest in the Paleolithic era) had gone extinct with the end of the last ice age. And that meant a new landscape could bloom.

That native flora that flourished brought the Spokane area root vegetables such as camas bulbs that grew abundantly.

WSU archaeology researcher Molly Carney studied how often Indigenous tribes used camas root and found the onion-like bulbs were a critical part of the cuisine, according to a WSU News article from earlier this year.

Camas bulbs grow in spring but were cultivated annually, according to a 2017 article in Edible Idaho.

A researcher studying how the Kalispel Tribe of Indians cooked camas bulbs observed that the onion-like vegetable could be roasted for 24 to 48 hours in a large embedded earth oven to cook off the inedible sugar compound called inulin, according to a 2007 research article in the Center for the Study of First Americans at Texas A&M University.

After this long cooking process, a thin layer of sugar formed around the outside of the bulb and acted as a natural preservative, so although camas bulbs grow exclusively in the spring, they could be stored and eaten for years, according to the 2007 article.

By the 17th century the Indigenous communities up north likely had access to corn, beans and squash, according to a 2016 article examining indigenous food history in the Journal of Ethnic Foods. Squash was already in North America. Maize and legumes cultivated by the resourceful tribes in what is now South America were also probably already in the northwest Americas.

Potatoes had also likely made their way from Indigenous farmers in what is now Bolivia to the Olympic Peninsula, according to a 2010 research article published in Euphytica, a peer-reviewed scientific plant breeding journal that consulted with members of the Yakama, Makah and Haida nations.

These became staples for most residents because they were easy to grow, which was especially good for tribes that enjoyed transient lifestyles combining hunting-gathering and plant domestication.

Fruits and herbs

Huckleberries are native to what is now known as the Northwest, but many other berries and herbs grew in abundance nearby and added sweet flavors to meals.

The red and Evergreen huckleberries grew near Spokane-based tribes, as well as thimbleberries, bunchberries and salmonberries, according to the Oregon State University Extension Service Plant Community.

Edible hazelnut plants grew mostly in moist soil, according to a list of native plants from the Washington Native Plant Society Columbia Basin Chapter. These could be adapted and then harvested as food. Elderberries and serviceberries also grew naturally and produced small dark fruit that would have been available to many of the region’s tribes, the plant society wrote.

Chokecherry trees bloomed with edible red berries in late spring, and in fall the local red-osier dogwood berries would ripen, according to the plant society.

These were sometimes paired with locally picked raspberries or blueberries, and then served in butternut squash during the autumn seasons, according to the 2007 Journal of Ethnic Foods article.

Wild mint, licorice, rose hips and dandelion were nutrient-rich and often boiled into medicinal teas, according to the American Indian Health & Diet Project.