How forensic genealogy helped solve a 62-year-old Spokane murder

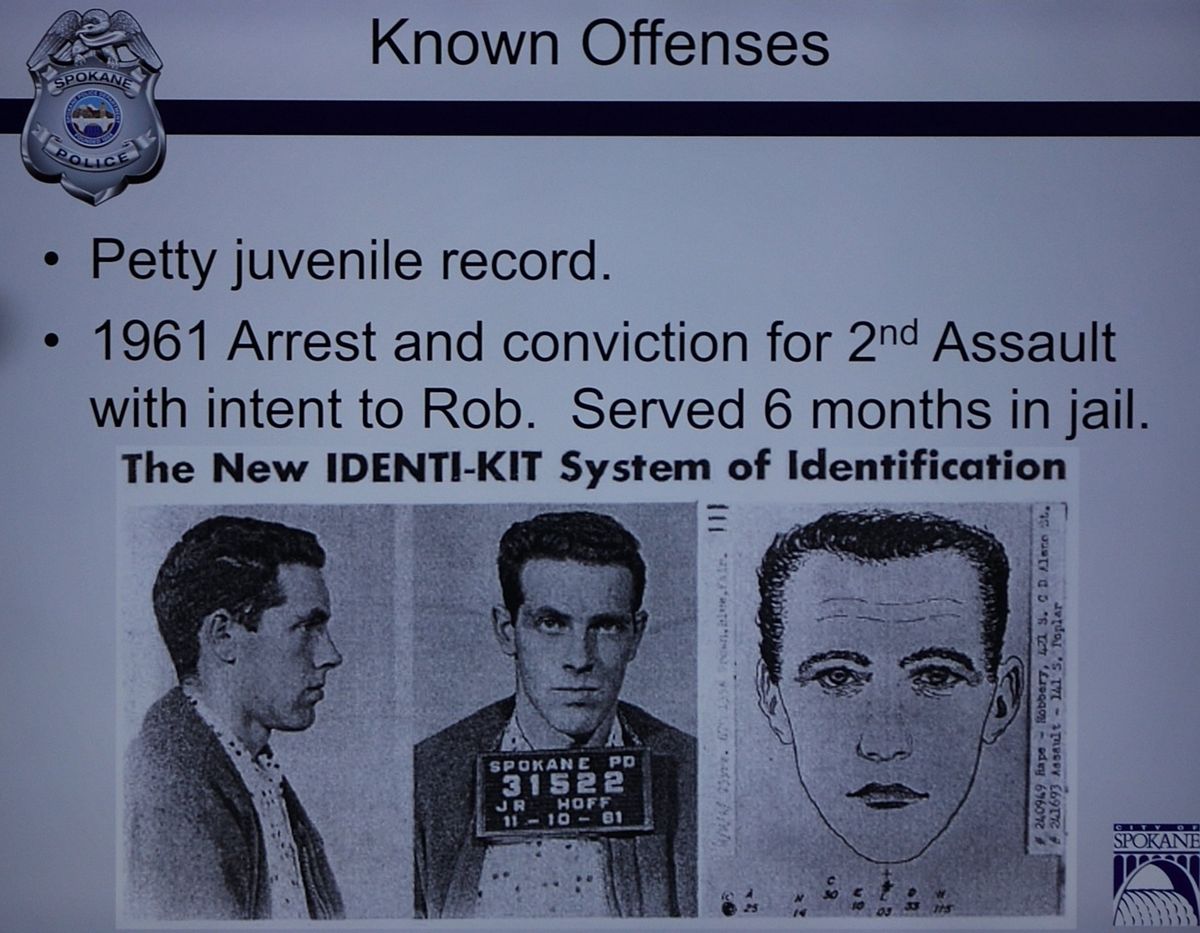

As police worked for decades to find a little girl’s killer and speculation often ran rampant, John Reigh Hoff never made it onto a list of suspects or into a newspaper story.

But in the new world of forensic genealogy, his name almost instantly rose to the top.

The 1959 murder of Candice “Candy” Elaine Rogers was solved by Spokane police thanks to the burgeoning science of forensic genealogy, which taps into DNA records in search of a match with samples taken from a crime scene.

The key development in the 9-year-old’s murder case didn’t come until more than 40 years after her killing, when investigators were able to isolate a DNA sample from semen found on her clothing. It was a feat not possible with the forensic technology available in 1959.

Although it ruled out one leading suspect, the DNA sample turned up no matches in the federal government’s DNA database, once again leaving police with little evidence to go on.

In the years since, however, the science of forensic genealogy has become a powerful tool for police across the country. Millions of people have taken samples of their own DNA in search of more information about their ancestry, with many choosing to allow their genetic information to be used in police investigations.

Simultaneously, the technology allowing forensics experts to repair and analyze DNA samples – and compare them to the public databases of DNA samples – has only improved.

It’s the same practice that led to the high-profile conviction of “Golden State Killer” Joseph James DeAngelo in 2020. DeAngelo committed more than a dozen murders and many more rapes in California in the 1970s and 1980s, but eluded investigators until he was identified through forensic genealogy.

Earlier this year, Spokane police and Washington State Police Forensic Scientist Brittany Wright reached out to Texas-based company Othram, which touts its ability to take tiny fragments of DNA and compare them to databases full of DNA samples from people it says have chosen to have them cataloged.

“The Candy Rogers DNA was very difficult to crack,” explained Spokane Police Sgt. Zac Storment. “We’d presented it to another lab last year, in 2020, hoping they could do it. They declined it, they declared the DNA too degraded to work.”

The DNA sample from Rogers’ clothing was degraded, but Othram built a genealogical profile from it. Using that sample, Othram narrowed down the list of potential suspects to three brothers, including Hoff, all of whom were dead.

David Mittelman, the founder and CEO of Othram, said the company employs DNA sequencing and other methods to make use of evidence that would otherwise be too degraded for a search.

It’s uses thousands of DNA markers to learn a lot about the ancestry of whomever the sample was from, be it a criminal suspect or an unidentified victim.

It’s not that the DNA databases are so large, Mittelman said, but that the number of DNA markers used in the comparison are so voluminous.

Sometimes, Othram can narrow the pool of potential suspects to a few brothers, as in Hoff’s case. (The analysis can home in on a single generation of a family with a shared ancestry, but the DNA shared between siblings is too similar to genealogically distinguish). In other cases, the pool of potential suspects is larger.

The “goal is to not really find the person, but to progressively narrow” the list of people who could be the source of the DNA sample, Mittelman said.

Even then, Mittelman stressed that Othram doesn’t solve cases, but only provides investigative leads.

“Usually a case has never hinged just on DNA,” Mittelman said.

In the Rogers investigation, the evidence was handed back to Storment, who was the latest in a line of Spokane police detectives to work the case. He found that one of the brothers had living relatives, including a daughter.

Storment obtained a DNA sample from Hoff’s daughter, and analysts concluded that it was 2.9 million times more likely that Hoff’s daughter was a genealogical match to the semen sample found on Rogers’ clothing than a random member of the public would be.

Looking for absolute certainty, Storment obtained a search warrant to exhume Hoff’s body.

The DNA sample taken from Rogers’ clothing was 25 quintillion times more likely that it was Hoff’s DNA than a random member of the public’s.

Hoff, who killed himself in 1970, was identified as Rogers’ killer.

While many of the cases that garner significant media attention are decades-old crimes like Hoff’s, Othram said the technology is and should be used for contemporary crimes and unsolved cases as well. Earlier this year, Othram helped identify a man found dead in Mississippi in 2016.

Mittleman expects the technology to only become more common in police work.

“We’ve got a tremendous momentum,” Mittelman said.

He believes it can be used to help identify a different class of criminal – the one that is hiding in plain sight.