His ‘Dreamscape’: Spokane-raised veteran Steve Yedinak publishes collection of his comrades’ war stories

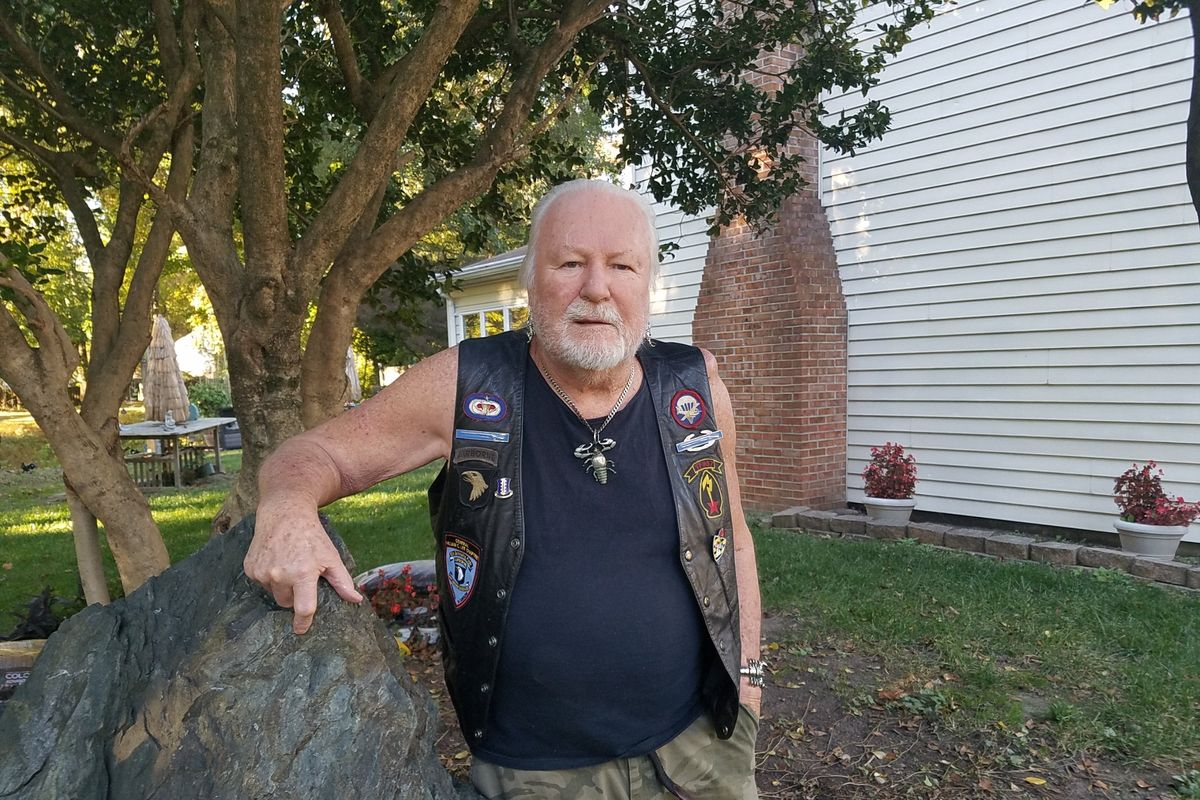

Veteran and author Steve Yedinak was born in Colfax and grew up just off the campus of Gonzaga University where, after finishing high school at Gonzaga Prep, he would go on to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Yedinak’s college studies centered on psychology. But he chose to join the Army, following in his father’s footsteps.

After graduating from GU in 1963, Yedinak, 81, accepted a commission in the Army, beginning a 26-year career in the Army Special Forces and Airborne Infantry, including five years in the 101st Airborne Division and two tours in Vietnam.

“The Korean War veterans at Gonzaga University really helped to save my life,” Yedinak said. In his later years at Gonzaga, he had started to spend too much time “socializing,” but a little encouragement, both from his athletic coaches and the veterans he looked up to, put him back on track.

“They saw something in me that I didn’t see,” he said.

Looking back, Yedinak realized that an instinct for self-direction, perhaps even leadership, came to him early. His first job, one he managed to get on his own, was delivering papers for The Spokesman-Review. From ages 11 to 13, he “walked the route … and personally collected monthly payments.”

His personal drive and a lifelong desire to help and support others would follow him through military training and onward through his various tours. But the things that followed him back home were another story.

Yedinak’s time in Vietnam would haunt him long after returning to the United States.

Yedinak’s memoir, “Hard to Forget: An American With the Mobile Guerrilla Force in Vietnam,” published by Random House in 1998, is a collection of declassified stories from Yedinak’s days as a U.S. Army captain and Green Beret, volunteering to lead what later became known as the “Mobile Guerrilla Force.” Before his retirement in 1989, Yedinak would achieve the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Upon returning home, Yedinak began experiencing anxiety and repetitive nightmares, among other symptoms. But it was only recently that he received an official post traumatic stress disorder diagnosis. By that time, Yedinak had begun the healing process on his own.

“I guess I finally thought I was strong enough … to go through the system and see what it had to say,” he said.

The process took several months, moving through a series of meetings with specialists before a “rather lengthy” meeting with the psychologist who would make the final determination.

Decades previous, coming to terms with the horrors he saw during his overseas tours and the traumas he brought back seemed to him, as it did to so many others, insurmountable. But for Yedinak, writing a memoir proved to be a catalyst for recovery.

“ ‘Hard to Forget’ helped me greatly,” he said. “I no longer suffer the elongated and debilitating nightmares that persisted for 25 years.”

Just getting it all out on paper was a help in itself. But the ability to share his story with family, friends and fellow soldiers, to open the door for greater understanding, was life-changing, he said.

Yedinak has since written other books on different topics, but his most recent, “Dreamscape: American Veterans Share Post-War Trauma,” published in August by SMY Books, returns to the themes of his first.

This time around, Yedinak’s aim was to help other veterans the way writing “Hard to Forget” helped him. To that end, “Dreamscape” is a collection of stories drawn from 26 veterans from Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Out of 26, only four contributors asked to remain anonymous.

“I thought if I could help myself … I might be able to help others,” he said.

The process of writing “Hard to Forget” was lengthy and cathartic, his wife, Tracy Yedinak, said. And returning to the subject in “Dreamscape,” writing from their new home in Newport News, Virginia, proved equally so.

“That was very emotional, but this really hit home … for both of us,” she said. “He would go through periods where I could tell … it was emotionally too much for him. I could see it playing out in his demeanor.”

But with the support system Yedinak has built, both for himself and the sources interviewed for “Dreamscape,” she knew he would be able to finish the project.

“It took a while, but I believe it was a healing process … a better healing process than the participants knew at the time,” she said.

Copies of Yedinak’s works are available at smybooks.com.