Egypt bets on ancient finds to pull tourism out of pandemic

CAIRO — Workers dig and ferry wheelbarrows laden with sand to open a new shaft at a bustling archaeological site outside of Cairo, while a handful of Egyptian archaeologists supervise from garden chairs. The dig is at the foot of the Step Pyramid of Djoser, arguably the world’s oldest pyramid, and is one of many recent excavations that are yielding troves of ancient artifacts from the country’s largest archaeological site.

As some European countries re-open to international tourists, Egypt has already been trying for months to attract them to its archaeological sites and museums. Officials are betting that the new ancient discoveries will set it apart on the mid- and post-pandemic tourism market. They need visitors to come back in force to inject cash into the tourism industry, a pillar of the economy.

But like countries elsewhere, Egypt continues to battle the coronavirus, and is struggling to get its people vaccinated. The country has, up until now, received only 5 million vaccines for its population of 100 million people, according to its Health Ministry. In early May, the government announced that 1 million people had been vaccinated, though that number is believed to be higher now.

In the meantime, authorities have kept the publicity machine running, focused on the new discoveries.

In November, archaeologists announced the discovery of at least 100 ancient coffins dating back to the Pharaonic Late Period and Greco-Ptolemaic era, along with 40 gilded statues found 2,500 years after they were first buried. That came a month after the discovery of 57 other coffins at the same site, the necropolis of Saqqara that includes the step pyramid.

“Saqqara is a treasure,” said Tourism and Antiquities Minister Khaled el-Anany while announcing the November discovery, estimating that only 1% of what the site contains has been unearthed so far.

“Our problem now is that we don’t know how we can possibly wow the world after this,” he said.

If they don’t, it certainly won’t be for lack of trying.

In April, Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s best-known archaeologist, announced the discovery of a 3,000-year-old lost city in southern Luxor, complete with mud brick houses, artifacts and tools from pharaonic times. It dates back to Amenhotep III of the 18th dynasty, whose reign (1390–1353 B.C.) is considered a golden era for ancient Egypt.

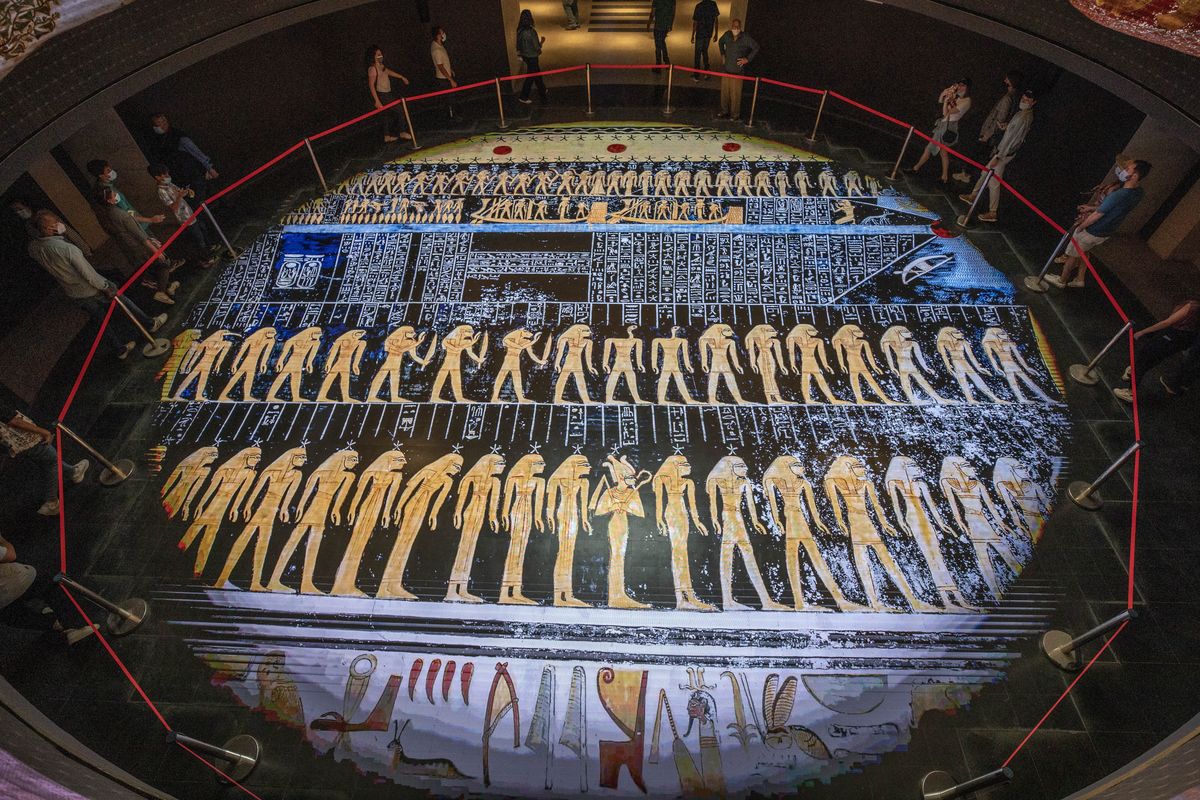

That discovery was followed by a made-for-TV parade celebrating the transport of 22 of the country’s prized royal mummies from central Cairo to their new resting place in a massive facility farther south in the capital, the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

The Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh is now home to an archaeological museum, as is Cairo’s International Airport, both opened in recent months. And officials have also said they still plan to open the massive new Grand Egyptian Museum next to the Giza Pyramids by January, after years of delays. Entrance fees for archeological sites have been lowered, as has the cost of tourist visas.

The government has for years played up its ancient history as a selling point, as part of a yearslong effort to revive the country’s battered tourism industry. It was badly hit during and after the popular uprising that toppled longtime autocrat Hosni Mubarak and the ensuring unrest. The coronavirus dealt it a similar blow, just as it was getting back on its feet.

In 2019, foreign tourism’s revenue stood at $13 billion. Egypt received some 13.1 million foreign tourists — reaching pre-2011 levels for the first time. But in 2020, it greeted only 3.5 million foreign tourists, according to the minister el-Anany.

At the newly opened National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Mahmoud el-Rays, a tour guide, was leading a small group of European tourists at the hall housing the royal mummies.

“2019 was a fantastic year,” he said. “But corona reversed everything. It is a massive blow.”

Tourism traffic strengthened in the first months of 2021, el-Anany, the minister, told The Associated Press in a recent interview, though he did not give specific figures. He was optimistic that more would continue to come year-round.

“Egypt is a perfect destination for post-COVID in that our tourism is really an open-air tourism,” he said.

But it remains to be seen if the country truly has the virus under control. It has recorded a total of 14,950 deaths from the virus and is still seeing more than a thousand new cases daily. Like other countries, the real numbers are believed to be much higher. In Egypt, though, authorities have arrested doctors and silenced critics who questioned the government’s response, so there are fears that information on the true cost of the virus may have been suppressed from the beginning.

Egypt also had a trying experience early on in the pandemic, when it saw a coronavirus outbreak on one of its Nile River cruise boats. It first closed its borders completely until the summer of 2020, but later welcomed tourists back, first to Red-Sea resort towns and now to the heart of the country — Cairo and the Nile River Valley that hosts most of its famous archaeological sites. Visitors still require a negative COVID-19 test result to enter the country.

In a further cause for optimism, Russia said in April that it plans to resume direct flights to Egypt’s Red Sea resort towns. Moscow stopped the flights after the local Islamic State affiliate bombed a Russian airliner over the Sinai Peninsula in October 2015, killing all on board.

Amanda, a 36-year-old engineer from Austria, returned to Egypt in May. It was her second visit in four years. She visited the Egyptian Museum, the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization and Islamic Cairo, in the capital’s historic center.

She had planned to come last year, but the pandemic interfered.

“Once they opened, I came,” she said. “It was my dream to see the Pyramids again.”

El-Rays, the tour guide, says that while he’s seeing tourists starting to come in larger numbers, he knows a full recovery will not happen overnight.

“It will take some time to return to before corona,” he said.