We the People: The ‘pursuit of happiness’ aimed to squelch the ‘divine right of kings.’ But its ideals can be elusive

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s questions: What does “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” mean? And what founding document first featured the phrase?

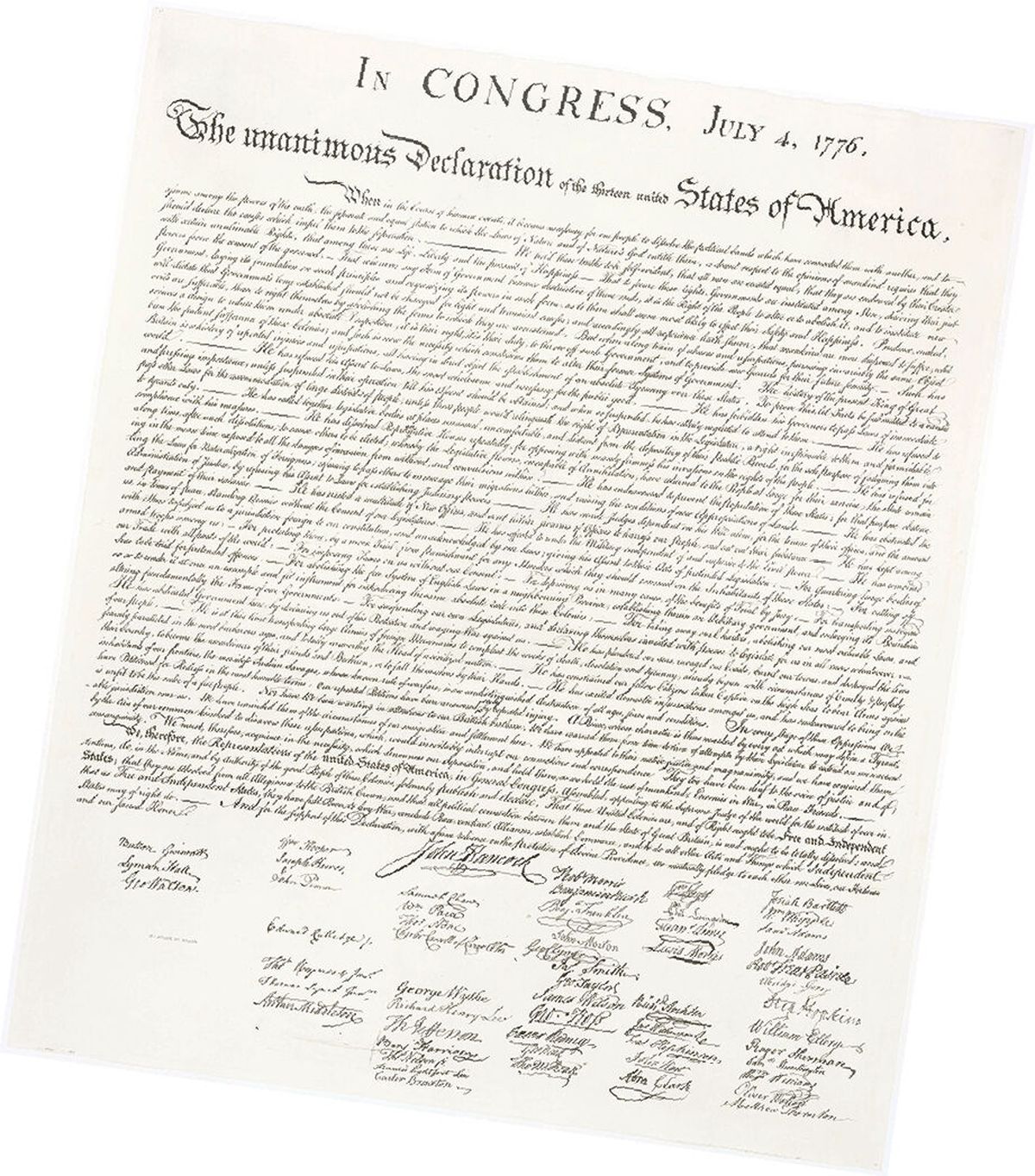

The correct answer is the Declaration of Independence, which formally separated the 13 colonies from Great Britain. The full quote reads, “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The declaration was written by Thomas Jefferson and was signed by the founding fathers on July 4, 1776. We celebrate the Fourth of July every year to commemorate its signing.

Thomas Jefferson’s goal when writing the declaration was not only to declare the 13 colonies free from royal subjugation, but also to convince his fellow colonists and the international community that the colonies were correct to declare themselves free and should be supported in doing so. He presented the facts of the case, not unlike legal proceedings today, and convincingly argued that the 13 colonies were free and right to declare themselves a new nation.

We’ve heard the words, “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” so often that they have lost some of their gravitas, but Jefferson and the other founders were truly radical in their ideas when compared to the norms of their time. To better understand the circumstances and risks taken by the founders, let’s look at the historical context of life under British rule.

For centuries, British subjects had lived under a governmental regime based upon the Divine Right of Kings. This meant that they believed that the king was chosen by God to be king and to rule over the people. The king’s will was, by extension, God’s will. This belief structure also meant that the people were utterly subjugated and that all of their belongings, their labor and their very lives were the king’s property, to do with as he pleased.

This system gave the king total and absolute authority to do whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted, for all of time. In other words, the king was a dictator and often a brutal one. In this system, to criticize the king’s orders was treason, punishable by the most gruesome torture and death that could be devised, often designed to keep the condemned alive as long as possible to prolong his suffering. This was the possible fate Jefferson and his colleagues faced if they failed.

So you can see how dangerous it was for Jefferson to reject the accepted norms of society and declare himself and all the colonists free of King George III’s rule. Even more radical was his rejection of the Divine Right of Kings and the declaration that a government should be determined by the will of the people, rather than the will of kings. The revolutionary ideals included in the declaration became the founding philosophy of this nation and the basis for what we now call the American Dream.

The philosophical ideals expressed in the declaration, that each man has equal, innate and unalienable rights, has never fully materialized. My use of man, rather than person, points out an inherent contradiction in the founders’ ethos. Female Americans were excluded entirely. Even today, women lack full and equal rights, despite almost a centurylong effort to pass a constitutional amendment that would ensure equality of rights under the law. The Equal Rights Amendment was originally drafted by Alice Paul in 1923, shortly after women were given the right to vote. It was passed by Congress in 1972 but has yet to be fully ratified.

Not all men were included in Jefferson’s vision of equality either. When the founders affirmed that “all men are created equal,” in practice they meant “all white, Christian, men who own land are created equal.” The equality enshrined in the declaration did not extend to white men under 21, nor white men without property.

The 1790 Naturalization Act extended the right to become citizens and thus exercise the right to vote to all white male immigrants of age. In 1828, non-Christian men who were white and Jews (who were not considered white at the time) became able to vote. In 1856, the requirement of land ownership was eliminated, allowing all white men 21 or older to vote. White women were not permitted to vote until 1920, and no one aged 18 to 20 was permitted to vote until 1971.

For communities of color, the path to free exercise of their voting rights would be much longer. While the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forbids denying men voting rights based on race, Black women and men in America were not permitted equal rights until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed. It is shocking to think how, in 245 years of independence from Britain, our fellow Americans were only permitted full use of their right to vote for 76 of those years – less than a third of the time.

For the citizens of U.S. Territories, including Puerto Rico, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands, their path to voting rights has further to go. Citizens of U.S. Territories are U.S. citizens. Regardless, they cannot vote in presidential elections and do not have representatives in Congress. Some argue that these citizens should be allowed both, but the issue has become stuck in political power struggles. It appears that we as a nation have a lot more work to do to truly embody the courageous spirit of the declaration and the ideals expressed therein.

Pip Cawley is a Ph.D. candidate of political science at Washington State University in Pullman.

This article is part of a Spokesman -Review partnership with the Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University.