School name finalist: John Oakley left indelible mark on students, athletes during 36-year career

Editor’s note: The Spokane school board is expected to pick the names of three new middle schools on Wednesday. This story is part of a series examining the finalists for those names.

John Oakley’s original dream was to help at-risk students as a probation officer.

But upon applying to Eastern Washington University to complete his bachelor’s degree, a counselor convinced the Ferris High School graduate to switch paths.

“He said, ‘You need to go into teaching,’ ” said Debbie Oakley, John’s widow. “If you want to make a difference in people’s lives, you do it before the kids get in trouble.”

It was advice that proved prophetic. John Oakley began a 36-year career with Spokane Public Schools in 1980, completing his student-teaching as Mount St. Helens blew its top. Those years spent coaching youngsters in the basketball gym, on the baseball diamond and the wrestling mat, as well as teaching at the front of the classroom, were cut short by a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, in January 2015. Oakley died a little less than two years later but continued teaching and coaching through the first part of 2016.

Son Adam Oakley, now the principal at Longfellow Elementary School, said his dad was driven by a desire to help all his students, not just the strongest and fastest.

“It was every kid, every day,” said Adam Oakley, who along with his brother, Aaron, coached baseball with their dad at Sacajawea Middle School before he died. “It didn’t matter if you were the best athlete. That’s how he lived as a teacher and a coach.”

The coaching career also landed John Oakley a coveted spot near the action for college basketball’s most ascendant program of the past 20 years. In the late ‘90s, a friend of the family through sports approached Oakley about operating the scoreboard at Gonzaga University men’s basketball games. That was before the historic tournament runs, No. 1 rankings and national championship contests, but for the next 18 years John Oakley was a front-row witness of the team’s rise.

“He’s been there for all of it,” Adam Oakley said.

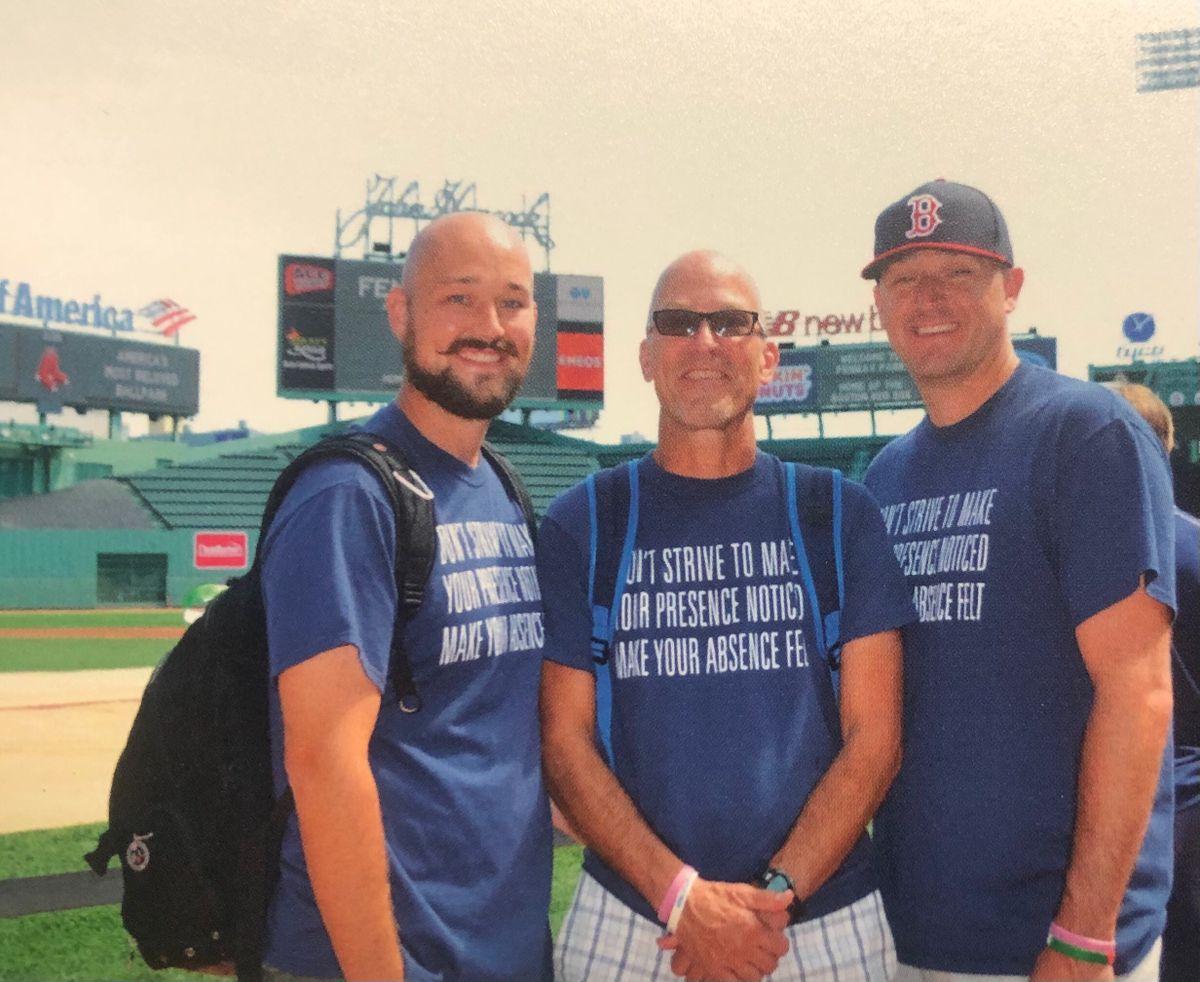

The 2015 ALS diagnosis allowed John Oakley to catch a glimpse of the effect he’d had teaching and coaching generations of Spokane kids, his family said. After they received the diagnosis at the University of Washington, John Oakley immediately began drafting a “bucket list” that included trips to Major League Baseball stadiums with his sons.

“We stopped in Leavenworth, and John went for a walk,” Debbie Oakley said of the trip back. “He found one of those inspirational signs, and it said, ‘Work for a cause not for applause. Live life to express not to impress. Don’t strive to make your presence noticed. Just make your absence felt.’ That was his motto.”

Adam Oakley organized a GoFundMe page as a way to pay for a trip to the East Coast. They’d started with a goal of $10,000, but more than 320 donors ended up contributing, leaving messages of remembrance along with $24,403 to help tick off items on the bucket list.

“He got to have a living memorial. Teachers don’t get that,” Adam Oakley said. “Retired teachers, they don’t get to hear the impact they’ve had.”

That summer, the Oakley sons and father visited five ballparks and the baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, in six days. At each park, the team had heard of John Oakley’s story and rolled out the red carpet, including at Fenway Park, where John Oakley got to write his name inside the massive left field wall known as “The Green Monster.”

At each stop, John Oakley would ask rhetorically about the praise, why me?

“I don’t think he ever realized that he deserved it,” Adam Oakley said.

But his students did. When he returned that fall, many wrote birthday cards for their teacher. Among them was Declan Sklut, who played ball at Gonzaga Preparatory after being coached by Oakley.

“I will never forget what you taught me the two seasons I played for you,” Sklut wrote. “You did not make any adjustments on my swing or teach me to get more movement on my curve, you taught me things that are so much more important.

“You taught me what playing the game the right way means,” Sklut continued. “You taught me how and when to control my emotions, how to stay calm, how to accept failure but continue striving for success, to be courageous, to appreciate and cherish every opportunity that I get.”

The Oakleys count themselves blessed that John got to see those messages before his death at age 59. While they’re flattered by his nomination, along with Holocaust survivor and freedom fighter Carla Peperzak and York, the Black enslaved member of the Lewis & Clark expedition, the ability to retell John Oakley’s story through the selection process is its own reward.

“More than anything, it’s an honor for the nomination alone,” Debbie Oakley said.

“Four years ago, we were telling these stories at a memorial,” Adam Oakley said. “To have it live on would be incredible.”