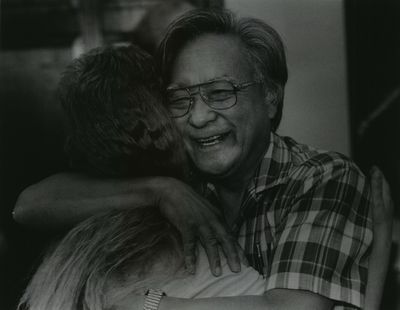

School name finalist: Denny Yasuhara was devoted to students and civil rights

Editor’s note: The Spokane school board is expected to pick the names of three new middle schools on Wednesday. This story is part of a series examining the finalists for those names.

Before Denny Yasuhara was a beloved math and science teacher at Spokane Public Schools, before he was a relentless fighter for dignity and fairness for his fellow Japanese Americans, and before he took on the local Democratic Party, Washington State University and the federal government, he was just a teenager in Bonners Ferry. And he liked to build model airplanes.

One of his favorite models, an English airplane, was dangling from his ceiling when a U.S. marshal showed up. The visit wasn’t long after President Franklin Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. The order cleared the way for local authorities to incarcerate about 120,000 Americans with Japanese ancestry, a racist reaction to Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor two months before.

“This measure,” Yasuhara said years later of Roosevelt’s order, “along with other laws of that era, presented a bleak future. The Japanese American was, in effect, told to go back home.”

The marshal demanded to know why Yasuhara had a foreign plane on display in his room, and seized the 14-year-old boy’s BB gun.

The gun was just the beginning for Yasuhara and his family. His mother was taken to the Boundary County sheriff’s office and interrogated.

The family’s businesses, the Grill Cafe and one of the largest hotels in the city, were boycotted by the region’s white citizens, and the family was forced to sell them at “a disastrous loss,” only to watch as the new owners sold them a few weeks later “at a tremendous profit, astronomical,” Yasuhara said in a 1980 Spokesman-Review article.

His classmates spat on him and told him he was to blame for National Guardsmen from Bonners Ferry being sent to Guadalcanal. His family packed up and moved to Spokane, where they thought a larger Asian American population would offer some protection and solace.

“It’s probably the most traumatic thing that ever happened to me,” Yasuhara said. “I was almost totally ostracized.”

Years later, students treated Yasuhara very differently. As “Mr. Yas,” he taught for nearly 30 years in Spokane, first at Logan Elementary, then at Garry Middle School, before retiring in 1989.

Since the family lived in rural Idaho, they avoided being forcibly relocated to the concentration camps the U.S. had set up for the nation’s Japanese Americans.

But it was something that shaped Yasuhara for the rest of his life.

“He really felt strongly about Japanese Americans, about civil rights, about human dignity for everyone. He really cared about people,” his wife of 38 years, Thelma, said in his 2002 obituary. “He was not afraid to speak out, even if he was all alone. He stood by his convictions.”

In 1954, he graduated from Washington State University and began a career in pharmacy. It wouldn’t last six years. He found it boring, and wanted to have more of an impact in his community. He was hired to teach at Logan in 1961.

Unlike pharmacy, with teaching he found his calling.

When he retired 28 years later, 100 former students threw a party to thank him. In an article about the party, they said he “taught us responsibility and accountability,” that he was “one of those teachers who people remember for their whole lives,” and that he “did the job my parents should have done” but he “did it for 20 to 30 kids every year.”

Inspiring students wasn’t his only vocation. He also had to call out and fight against, racism, and find ways to care for Japanese Americans.

In 1973, Yasuhara helped found Hifumi En on the South Hill, which he had originally envisioned in 1965 as a home for elderly, disabled or veteran Japanese Americans. Local money, along with federal grants, built the home, which exists to this day.

In 1977, along with the Japanese Americans Citizens League, he sued WSU, charging the university with discrimination.

Federal officials at the Office for Civil Rights dismissed the complaint, but it spurred the university to create an Asian American study program with a full professorship. In 1990, the university awarded Yasuhara the Alumni Achievement Award.

Perhaps most significantly, Yasuhara was involved in the creation of the federal Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted each survivor of the American internment camps $20,000 in reparations, and issued an apology for the government actions based in “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” More than 82,000 people received the money.

Still, Yasuhara was not done.

In 1992, local officials with the Democratic Party made racist comments about the then-owner of the Davenport Hotel, Patrick Ng of Hong Kong, and against Chris Marr, a Democrat who would later represent Spokane as a state senator.

In a guest column for The Spokesman-Review in 1993, Yasuhara called for an independent investigation, an apology to the city’s Asian American population and disciplinary action.

“The basic fabric of any free, democratic society is respect – respect for the dignity of each individual or group with that society,” he wrote. “Coming at a time of an alarming rise of hostility and violence against Asian Americans across America, as well as increasing hate crimes against those of Jewish ancestry and other peoples of color, it is deeply troubling to have legitimate concerns trivialized by local, state and congressional politicians and editorials in local papers.”

In 1995, the party apologized and settled the lawsuit Yasuhara and others brought against it.

Even then, Yasuhara wasn’t done.

In 1994, Denny Tetsuki Yasuhara received the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold and Silver Rays, from the Emperor of Japan for his contributions promoting ties between the U.S. and Japan, and the welfare of the Japanese American community. He was elected president of the Japanese American Citizens League the same year, a post he served for two years.

When he died of pancreatic cancer at 76, his obituary ran in the Washington Post and Japan Times.