School name finalist: Eugene Breckenridge graduated Whitworth with rave reviews and masters degree, but the Spokane School Board wouldn’t hire him

Editor’s note: The Spokane school board is expected to pick the names of three new middle schools on Wednesday. This is the first in a series of stories examining the finalists for those names.

In 1951, Eugene H. Breckenridge was working at the only job he could land: washing windows for a janitorial service in Spokane.

This was not what he envisioned after earning a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from West Virginia State College and a master’s degree in education from Whitworth College, where he was named 1951’s outstanding student-teacher.

Yet washing windows was the only position seemingly available even for a highly educated Black man at the time. By any reasonable standard, Breckenridge was qualified to teach multiple subjects to Spokane secondary school students, including science, math, English and history. But he lacked one key qualification: white skin.

The school district had no Black teachers in 1951, and the school board had no interest in hiring one. In the district’s entire history, only one Black teacher, Helen Dundee, had ever been hired. Dundee was a substitute teacher in 1936 who left after one year.

A better candidate than Breckenridge would have been hard to find. After his boyhood in Texarkana, Arkansas, Breckenridge had joined the Army during World War II, where he rose to the rank of master sergeant. He then went to college for his undergraduate degree, and was duly accepted into Whitworth’s master’s program to be a teacher.

Breckenridge paid his tuition by working at another of the jobs open to Black men in Spokane at the time, headwaiter at the Spokane Press Club. While getting his master’s degree, he became deeply involved with the Spokane chapter of the NAACP, beginning his lifelong commitment to racial justice and human rights.

His master’s thesis was, fittingly, an analysis of employment discrimination in Spokane. In 1950, he gave a speech to a Spokane church group, addressing the issue of fair employment in surprisingly optimistic terms. “The increasing number of enlightened businessmen, here in Spokane, who have recognized fair employment merely as good business sense, is happy news to all members of minority groups,” he said.

But the news wasn’t so happy when he graduated and his job application gathered dust at the school district.

Yet the power dynamics were shifting in Spokane. Carl Maxey had just become the first Black man to pass the state bar exam in the region, and he was ready and willing to take on employment discrimination. When Maxey found Breckenridge washing windows, he took action. He went to Spokane School Superintendent John Shaw and appealed to him on the grounds of basic fairness.

Shaw was open to this argument, but he explained his problem to Maxey: He had a recalcitrant school board. Shaw had tried to hire a Black teacher a few years earlier, but dropped the plan when he encountered too much resistance from the school board. The school board’s attitude: We’ve never had any racial problems in this school district. Why create any?

So Maxey tried a different – and tougher – approach with the school board. He threatened an NAACP lawsuit. The local chapter of the NAACP demanded public “clarification” of the district’s policy in “hiring qualified Negroes as teachers,” according to historian Dwayne A. Mack in his book, “Black Spokane.”

So in August 1951, the board “allowed” Shaw to hire Breckenridge to teach math and English at Havermale Junior High School. The Spokane Daily Chronicle reported that “he will be the first Negro to hold a teacher’s contract in Spokane,” which was at least close to the truth.

Toward the end of the 1951-1952 school year, the Chronicle checked in to see how this employment experiment had worked out. Very well, was the consensus. Breckenridge, said the paper, “had won the confidence of students, parents and his fellow teachers.”

“I was given the opportunity to work in the profession for which I had prepared myself,” Breckenridge told the Chronicle. “I believe I have been no better nor worse than any other teacher with the same qualifications. In some instances I might have been looked on as a curiosity. I have treated these boys and girls as ladies and gentlemen. I have tried to teach them to respect one another, and they have shown respect for me.”

By 1955, the district had hired two more Black teachers – a number that would continue to grow.

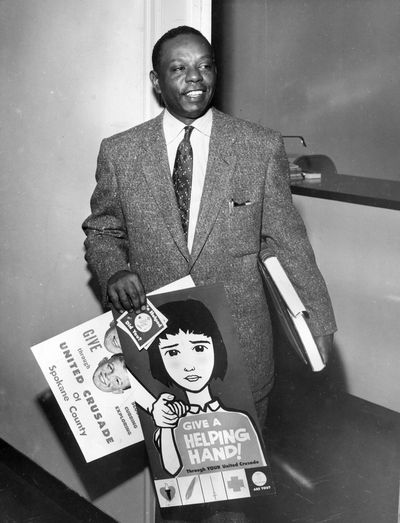

Breckenridge thrived in his profession, and by 1957 he had moved up to become a history teacher at Shadle Park High School. Meanwhile, he continued to serve as a local leader in racial justice and human rights causes, with organizations including the Spokane Council of Racial Relations, the Spokane Human Rights Council and the United Nations Association. He gave dozens, if not hundreds, of talks to church groups and civic groups. Whenever a panel convened to discuss racial relations in Spokane, Breckenridge was usually on it.

In 1967, the Washington Education Association presented him with its first Educator-Citizen of the Year Award at its annual convention. Yet his time in Spokane was drawing to a close. That year, he left for Tacoma to become the public school district’s supervisor of social studies. He rose steadily through the administrative ranks and by 1969, he was Tacoma’s administrative assistant for community affairs.

That same year, Whitworth College celebrated his achievements by awarding him an honorary doctorate. At the midyear commencement ceremony, the Whitworth president praised Breckenridge for “the distinguished and exceptional manner in which he has served as a leader in public education.”

In 1974, Breckenridge was named Tacoma’s assistant superintendent for affirmative action and community affairs. He was the district’s highest ranking Black administrator. One of his responsibilities must have been particularly close to his heart: implementing an action plan for hiring minorities.

He retired in 1977, and in 1986, he died at age 74. The Tacoma News-Tribune credited him with, among other accomplishments, playing a key role in the desegregating of Tacoma’s schools.