Billions – perhaps trillions – of cicadas emerging in 15 states. Is Washington among them?

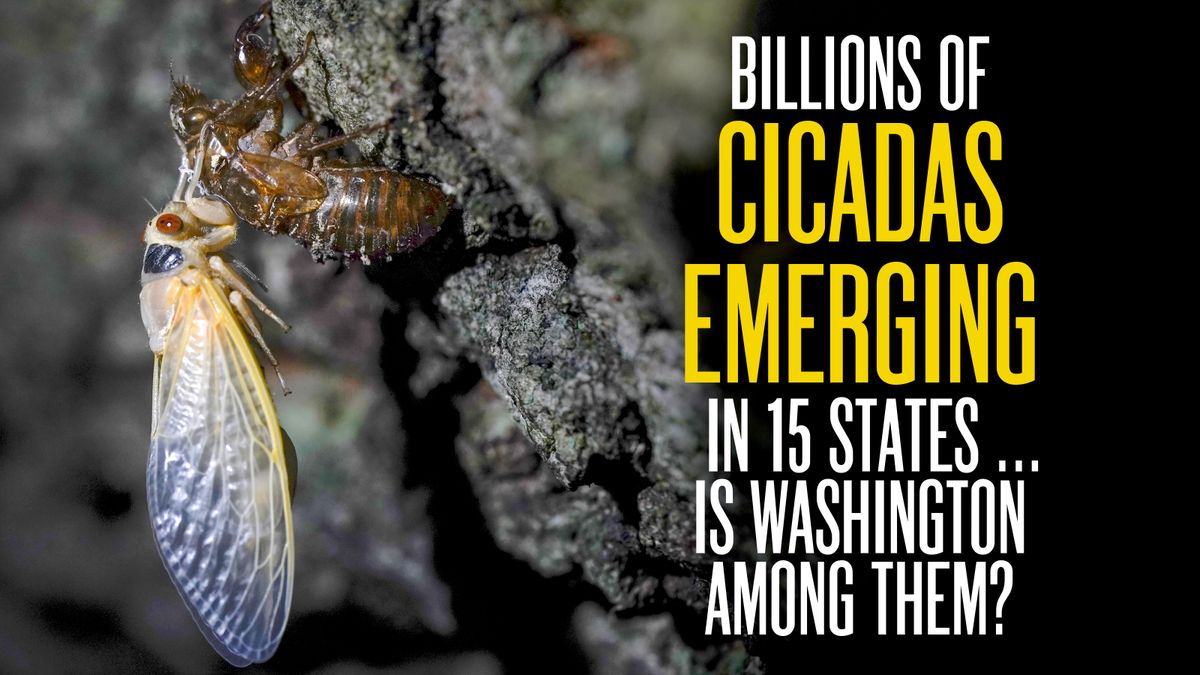

An adult cicada is seen in Washington, D.C., on Thursday. Trillions of cicadas are about to emerge from 15 states in the U.S. East. (Carolyn Kaster/Associated Press)

They’ve begun breaking through the soil like zombies from graves. Brood X cicadas, underground for the past 17 years, are emerging en mass to find a mate. In a week or so, billions – perhaps trillions – of the winged creatures with bulging red eyes will emit high-pitched mating calls that can collectively reach 100 decibels, equivalent to the volume of a lawnmower.

But stories of Brood X cicadas covering mailboxes, smashing into windshields or driving people indoors with their loud buzzing won’t happen here in the Evergreen State.

“We have cicadas, but not the species that make up Brood X,” said Washington state entomologist Richard Zack. “Things will be much quieter here.”

Which is good to know. After all, when it comes to insects, Washington sometimes makes big news. The first so-called murder hornet nest was found here and the destructive marmorated stink bug has taken up residence in 21 counties, including Spokane.

Even so, it’s not home to Brood X – the “X” being the Roman numeral for 10 – the largest of the cicada broods with a 17-year life cycle. Instead, their digs span 15 states across the Midwest and East Coast, as well as Washington, D.C.

“They require certain environmental conditions that we don’t have,” said Zack.

What’s more, even if Washington had the right weather and soil conditions to host Brood X, they’d have to make it over the Rocky Mountains, which is probably an impossible feat, he explained. “After the cicadas emerge, they don’t fly high. And they don’t live long either.”

Just long enough to discard their skins as they grow, create a ruckus, mate and lay eggs – all in less than 60 days.

About those skins, perhaps you’ve seen cicada exoskeletons littered around tree trunks or dangling from fence posts here in Washington. Chances are, those brittle, light brown shells were shed by Platypedia areolata, also known as the “orchard cicada, the common cicada of the Pacific Northwest Region,” according to the Washington State University Entomology Department.

Slightly smaller and more solitary than the Brood X variety, the orchard cicada emerges every four years and produces more of a soft clicking sound than a loud buzz. Also, with bulging black eyes instead of red, it doesn’t so strongly resemble a creature from a B-grade horror movie.

And more good news – Washington’s cicada species create far less of a racket than Brood X, said Zack. “Our cicadas don’t come out in gigantic numbers they way they do,” he said. This means their mating call sounds more like a serenade than a monstrous cacophony.

Regardless of the species – and there are roughly 190 of them in North America, according to the website cicadamania.com – most cicadas are big and noisy. They have antennae, six legs, and typically range in size from 1-2 inches long. During a large-scale emergence, they smack into people at picnics and outdoor weddings and their exoskeletons crunch like potato chips when stepped on.

Annoying, yes. Dangerous, no, said Zack.

“They don’t sting. They don’t bite, and they don’t devour crops or flowers,” Zack explained. Furthermore, they provide nourishment to birds, rodents, foxes and other animals, he said.

In fact, citizen scientist Dan Mozgai, who founded Cicada Mania in 1998, proclaims them as “the most amazing insects in the world.” And he pushes back on the term “invasion” to describe their ensemble arrivals, describing them instead as spectacular natural events performed by a native species.

For people dreading the Superbowl-like emergence of Brood X members, Mozgai hopes they will try to view it as part of a brilliant survival technique, he explained by email.

“The first wave of cicadas is like the guard and tackle of American football – they take the hit so the team can score,” he wrote while tracking early arrivals of Brood X in Virginia. “They’re there to be eaten so others can survive.”

An adult cicada is seen in Washington, D.C., on Thursday. Trillions of cicadas are about to emerge from 15 states in the U.S. East. (Carolyn Kaster/Associated Press)